Factoring is a foundational skill in algebra that unlocks the ability to simplify expressions, solve equations, and understand higher-level mathematics. Whether you're preparing for exams or building confidence in math, mastering factoring requires more than memorization—it demands a structured approach and consistent practice. This guide breaks down the process into actionable steps, provides practical tools, and shares proven strategies used by educators and students alike to achieve consistent results.

Understanding the Role of Factoring in Algebra

At its core, factoring is the process of breaking down a mathematical expression into simpler components—called factors—that, when multiplied together, produce the original expression. It’s the reverse of expansion. For example, expanding (x + 3)(x + 5) gives x² + 8x + 15; factoring x² + 8x + 15 returns (x + 3)(x + 5).

Factoring appears in various forms: from simple binomials to complex polynomials. It plays a critical role in solving quadratic equations, simplifying rational expressions, and even in calculus when analyzing limits or derivatives. Without strong factoring skills, progress in advanced math becomes significantly harder.

Despite its importance, many students struggle due to inconsistent methods or skipping foundational steps. The key lies not in speed but in accuracy and understanding each stage of the process.

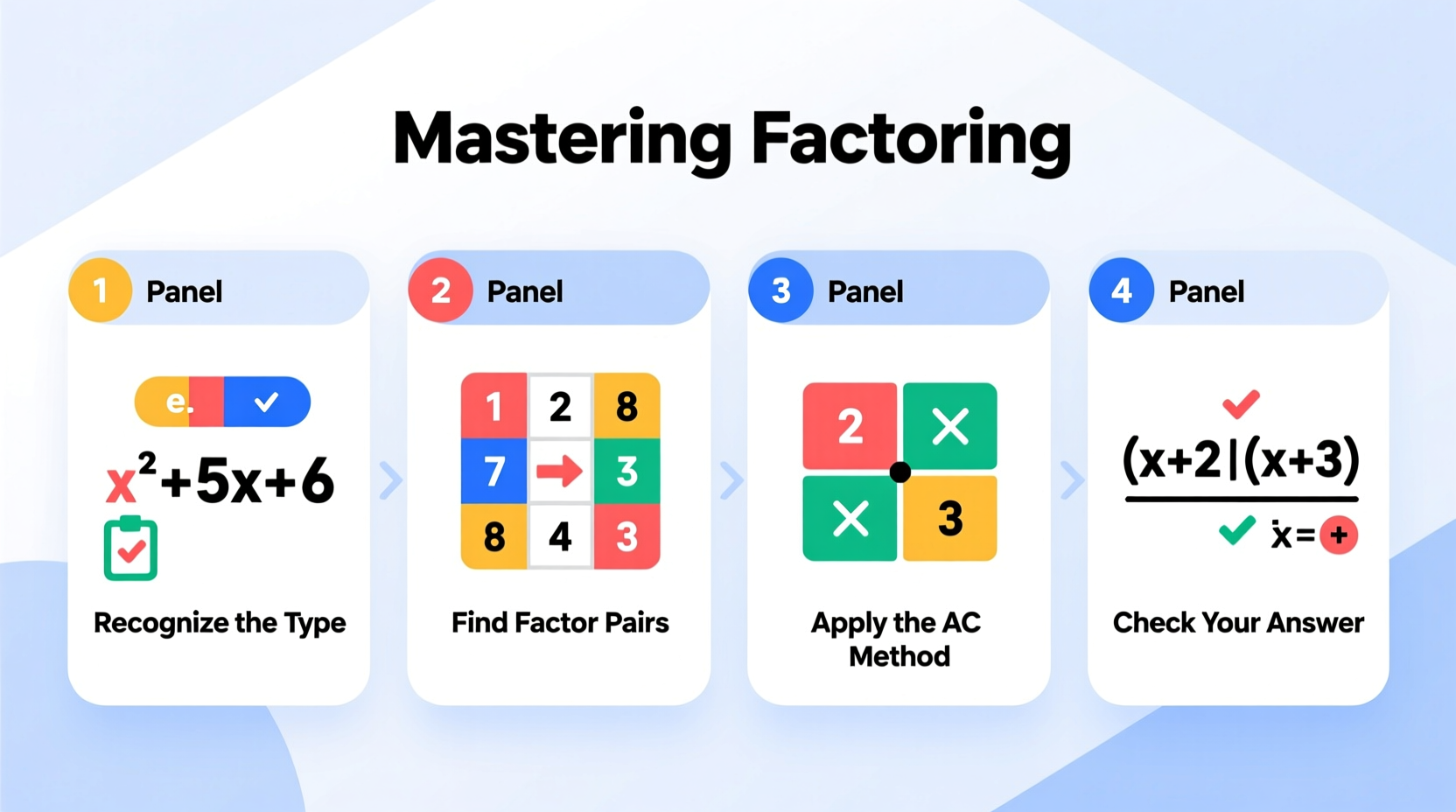

Step-by-Step Guide to Solving Common Factoring Problems

Follow this systematic method to confidently factor most algebraic expressions encountered in high school and early college math.

- Identify the type of expression: Determine whether you’re dealing with a binomial, trinomial, or polynomial with four or more terms. Each has different factoring techniques.

- Factor out the Greatest Common Factor (GCF): Before applying any other method, look for a common factor across all terms. For instance, in 6x³ + 9x², the GCF is 3x², so factor it out first: 3x²(2x + 3).

- Apply the appropriate factoring pattern:

- Difference of squares: a² – b² = (a + b)(a – b)

- Perfect square trinomials: a² ± 2ab + b² = (a ± b)²

- Trinomials of the form x² + bx + c: Find two numbers that multiply to c and add to b.

- Grouping: Used for four-term polynomials. Group terms in pairs and factor each pair separately.

- Double-check for further factoring: After initial factoring, examine each resulting factor to see if it can be broken down further. For example, x⁴ – 16 becomes (x² + 4)(x² – 4), and then (x² + 4)(x + 2)(x – 2).

- Verify by multiplication: Expand your final factors to ensure they reproduce the original expression.

Example: Factoring a Quadratic Trinomial

Factor: x² + 7x + 12

- No GCF beyond 1.

- Find two numbers that multiply to 12 and add to 7 → 3 and 4.

- Write as (x + 3)(x + 4).

- Check: (x + 3)(x + 4) = x² + 4x + 3x + 12 = x² + 7x + 12 ✓

Common Factoring Patterns and When to Use Them

Recognizing patterns accelerates problem-solving. The table below outlines major factoring types and their applications.

| Type | Form | Factored Form | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| GCF | ax + ay | a(x + y) | 5x + 10 = 5(x + 2) |

| Difference of Squares | a² – b² | (a + b)(a – b) | x² – 25 = (x + 5)(x – 5) |

| Perfect Square Trinomial | a² ± 2ab + b² | (a ± b)² | x² + 6x + 9 = (x + 3)² |

| Simple Trinomial | x² + bx + c | (x + m)(x + n) | x² – 5x + 6 = (x – 2)(x – 3) |

| Grouping | ax + ay + bx + by | (a + b)(x + y) | 2x + 2y + 3x + 3y = (2+3)(x+y)? No — correct grouping: 2(x + y) + 3(x + y) = (x + y)(2 + 3) |

Mastery comes from drilling these patterns until recognition becomes automatic. Practice identifying which method applies before attempting to factor.

Mini Case Study: From Struggle to Success

Sophia, a 10th-grade student, consistently scored below 70% on algebra quizzes, particularly on factoring quadratics. She would skip the GCF step and jump straight into guessing factor pairs, often making sign errors. Her teacher introduced her to a checklist-based approach and encouraged daily 15-minute drills focused on one factoring type at a time.

Within three weeks, Sophia began recognizing patterns faster. She started every problem by asking: “Is there a GCF?” Then, “Does this fit a known formula?” By systematically applying steps and checking answers, her quiz scores rose to 90%. More importantly, she reported feeling less anxious during tests because she had a reliable process to follow.

“Students who succeed in factoring aren’t necessarily the fastest—they’re the most methodical.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, High School Math Department Chair

Essential Checklist for Accurate Factoring

Use this checklist every time you factor an expression to minimize errors and build consistency.

- ☐ Look for a Greatest Common Factor (GCF) across all terms

- ☐ Count the number of terms to determine possible factoring strategy

- ☐ Check for difference of squares (two terms, subtraction, both perfect squares)

- ☐ For trinomials, verify signs and find factor pairs of the constant term that sum to the middle coefficient

- ☐ Try grouping if there are four or more terms

- ☐ Ensure all factors are fully simplified—can anything be factored again?

- ☐ Multiply factors back to confirm they match the original expression

Frequently Asked Questions

What should I do if a trinomial doesn’t factor evenly?

If no pair of integers multiplies to the constant term and adds to the middle coefficient, the trinomial may be prime (not factorable over integers). In such cases, use the quadratic formula or complete the square to solve related equations.

Can I factor expressions with variables in exponents?

Yes, substitution can help. For example, x⁴ – 5x² + 6 looks like a quadratic. Let u = x², so the expression becomes u² – 5u + 6, which factors to (u – 2)(u – 3). Substitute back: (x² – 2)(x² – 3).

Why is factoring still important in the age of calculators and apps?

While technology can factor quickly, understanding the process builds number sense, logical reasoning, and prepares students for advanced topics where conceptual insight—not just answers—matters. You can't rely on tools during exams or when learning new theories that assume factoring fluency.

Conclusion: Build Confidence Through Consistent Practice

Factoring isn’t about innate talent—it’s about disciplined practice and using the right strategies. Start with simple expressions, master each pattern, and gradually tackle more complex problems. Keep a notebook of common mistakes and review them weekly. Over time, what once seemed confusing will become second nature.

Mathematical confidence grows not from avoiding difficulty, but from persisting through it with a clear plan. Apply the steps, use the checklist, and learn from every error. With dedication, anyone can master factoring and open doors to greater success in algebra and beyond.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?