Understanding oxidation numbers is foundational to mastering redox reactions, balancing chemical equations, and interpreting electron transfer in chemical processes. While the concept may initially seem abstract, applying a systematic approach transforms it into a reliable and repeatable skill. This guide breaks down the process of determining oxidation numbers using clear rules, real-world applications, and practical strategies that build confidence in any chemistry student or professional.

What Is an Oxidation Number?

An oxidation number (or oxidation state) represents the hypothetical charge an atom would have if all bonds were completely ionic. It does not reflect the actual charge in covalent compounds but serves as a bookkeeping tool to track electron movement in reactions—especially redox (reduction-oxidation) processes.

Oxidation numbers help identify which atoms are oxidized (lose electrons) and which are reduced (gain electrons). Without accurate assignment, predicting reaction outcomes or balancing complex equations becomes nearly impossible.

“Oxidation states are the backbone of electrochemistry and stoichiometry—they turn abstract electron flow into measurable, predictable patterns.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Inorganic Chemistry Educator

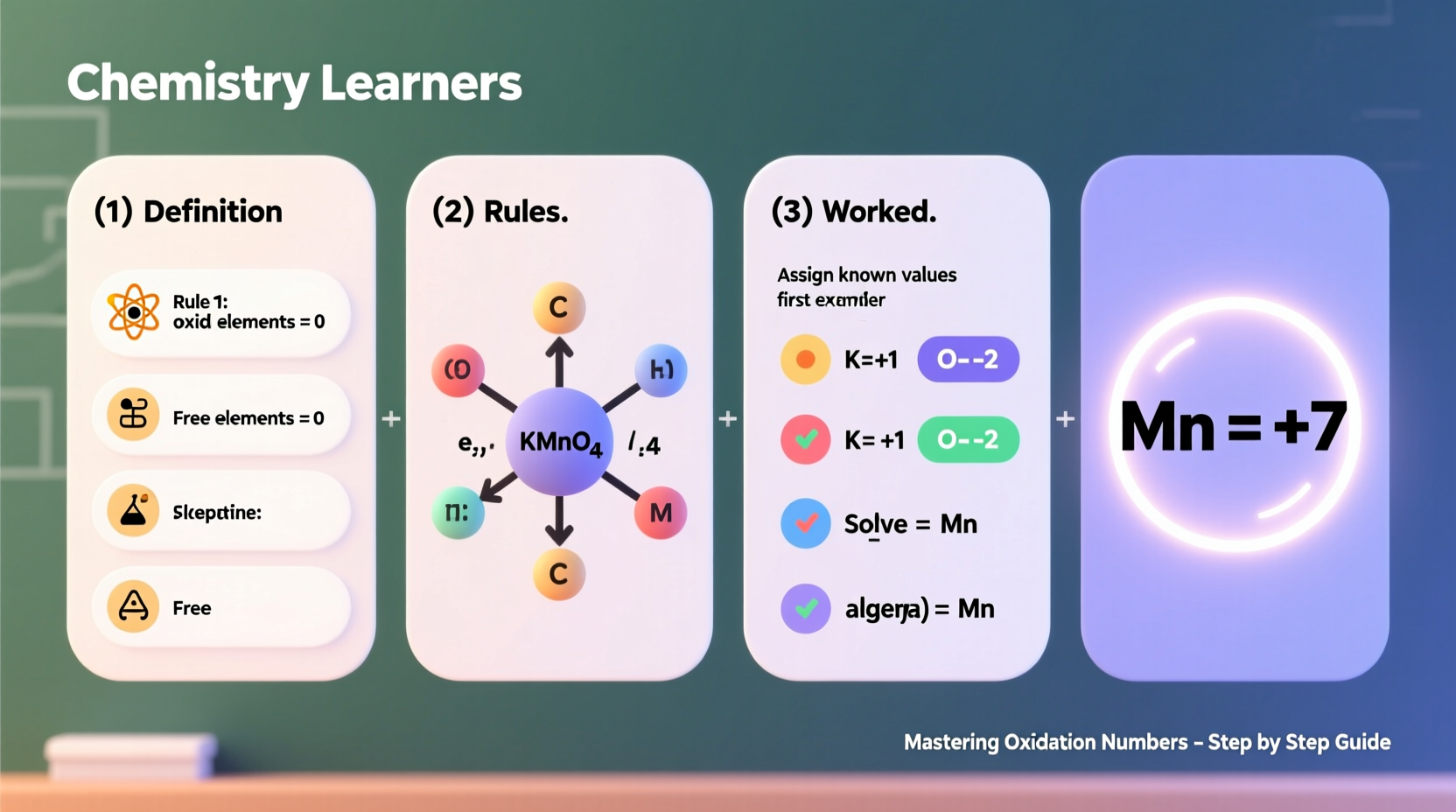

The Fundamental Rules for Assigning Oxidation Numbers

There are seven core rules universally accepted by IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) for assigning oxidation numbers. Mastery begins with memorizing and correctly applying these principles:

- Elements in their standard state have an oxidation number of 0. This includes diatomic molecules like O₂, H₂, N₂, and elemental solids such as Fe(s), Cu(s), or S₈.

- Monatomic ions have oxidation numbers equal to their charge. For example, Na⁺ has +1, Ca²⁺ has +2, and Cl⁻ has -1.

- Fluorine always has an oxidation number of -1 in compounds.

- Oxygen usually has -2, except in peroxides (like H₂O₂) where it’s -1, and when bonded to fluorine (e.g., OF₂), where it’s +2.

- Hydrogen is +1 when bonded to nonmetals (e.g., H₂O, HCl), but -1 when bonded to metals (e.g., NaH, CaH₂).

- The sum of oxidation numbers in a neutral compound is 0. For polyatomic ions, the sum equals the ion’s charge.

- In binary compounds with metals, Group 17 elements (halogens) typically have -1, Group 16 (oxygen family) -2, and Group 15 (nitrogen family) -3—unless overridden by more electronegative elements.

Step-by-Step Guide to Solving for Oxidation Numbers

Follow this structured method to confidently determine oxidation states in any molecule or ion:

- Identify the species: Is it a neutral compound, a polyatomic ion, or an element?

- List all atoms present: Write down each element and how many times it appears.

- Apply known oxidation rules: Assign fixed values based on the seven rules above.

- Set up an equation: Use algebra to represent the unknown oxidation number(s).

- Solve the equation: Ensure the total matches either zero (neutral compound) or the net charge (ion).

- Double-check consistency: Verify no rule was violated and electronegativity trends make sense.

Example: Find the oxidation number of sulfur in H₂SO₄

- H₂SO₄ is a neutral compound → total oxidation = 0

- Hydrogen: Each H = +1 → 2 × (+1) = +2

- Oxygen: Each O = -2 → 4 × (-2) = -8

- Let x = oxidation number of sulfur

- Equation: (+2) + x + (-8) = 0 → x - 6 = 0 → x = +6

Thus, sulfur in sulfuric acid has an oxidation number of +6—a hallmark of its highly oxidized state.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced students misapply oxidation rules under pressure. The following table highlights frequent errors and corrections:

| Mistake | Correct Approach | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Assuming oxygen is always -2 | Check for peroxides or fluorine compounds | In H₂O₂, O = -1; in OF₂, O = +2 |

| Treating hydrogen uniformly | Distinguish between covalent and hydride forms | H = +1 in H₂O, but H = -1 in NaH |

| Forgetting ion charges | Sum must equal ion charge, not zero | In SO₄²⁻, total oxidation = -2 |

| Ignoring elemental form | Free elements have oxidation number 0 | Cl₂(g) = 0; Cr(s) = 0 |

Real-World Application: Identifying Redox Reactions

Consider a lab technician analyzing the corrosion of iron in moist air. The reaction involves:

4Fe + 3O₂ + 6H₂O → 4Fe(OH)₃

To determine if this is a redox process:

- Fe starts as elemental (oxidation = 0)

- In Fe(OH)₃: Oxygen = -2, Hydrogen = +1 → Let x = Fe oxidation

- Each OH group contributes -1 → three OH groups = -3

- So x + (-3) = 0 → x = +3

Iron goes from 0 to +3—oxidation occurs. Oxygen in O₂ (0) becomes -2 in OH⁻—reduction occurs. This confirms a redox reaction, crucial for understanding rust formation and designing protective coatings.

Expert Checklist for Accurate Oxidation Number Calculation

Use this checklist every time you calculate oxidation states:

- ✅ Confirm whether the species is neutral or charged

- ✅ Assign known values first (F = -1, O = -2 unless exception, H = +1 or -1 accordingly)

- ✅ Account for all atoms in the formula

- ✅ Set up a simple algebraic equation

- ✅ Solve and verify the sum matches expected total

- ✅ Cross-check against electronegativity trends (higher EN elements take negative values)

- ✅ Review exceptions (peroxides, superoxides, hydrides, fluorine compounds)

Frequently Asked Questions

Can an element have more than one oxidation number?

Yes. Many transition metals and nonmetals exhibit variable oxidation states. For example, manganese can range from +2 (in MnCl₂) to +7 (in KMnO₄). This variability enables diverse reactivity and catalytic behavior.

Is oxidation number the same as formal charge?

No. Oxidation number assumes complete electron transfer (ionic model), while formal charge assumes equal sharing (covalent model). They serve different purposes: oxidation number tracks redox changes; formal charge helps assess molecular stability and resonance structures.

Why do some elements break the usual rules?

Electronegativity differences override general trends. For instance, oxygen is less electronegative than fluorine, so in OF₂, fluorine takes priority with -1, forcing oxygen to +2. These exceptions highlight the importance of hierarchy in rule application.

Conclusion: Build Confidence Through Practice

Mastering oxidation numbers isn’t about rote memorization—it’s about developing a logical framework for analyzing chemical behavior. By internalizing the seven key rules, practicing consistently, and learning from common errors, you gain a powerful lens for understanding reactions across general, organic, and inorganic chemistry.

Whether you're preparing for exams, conducting lab work, or advancing into electrochemistry, precise oxidation state determination lays the foundation for deeper insight. Start with simple compounds, progress to complex ions, and soon you’ll navigate even the most challenging redox scenarios with clarity and confidence.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?