Learning Japanese numbers is one of the first milestones for any language learner. While counting from one to ten may come quickly, navigating higher numbers—especially those with unique readings—can be tricky. The number 20 is a turning point in Japanese numeracy. It marks the beginning of compound structures and introduces learners to the concept of counter words and pronunciation shifts. Understanding how to correctly write and say 20 in Japanese lays the foundation for mastering larger numbers and improves fluency in everyday conversations.

The Basics: How to Say and Write 20 in Japanese

In Japanese, the number 20 has two primary forms: the Sino-Japanese (on'yomi) reading and the native Japanese (kun'yomi) reading. The most commonly used form is にじゅう (nijū), which combines “ni” (二), meaning \"two,\" and “jū” (十), meaning \"ten.\" Together, they literally translate to \"two tens.\"

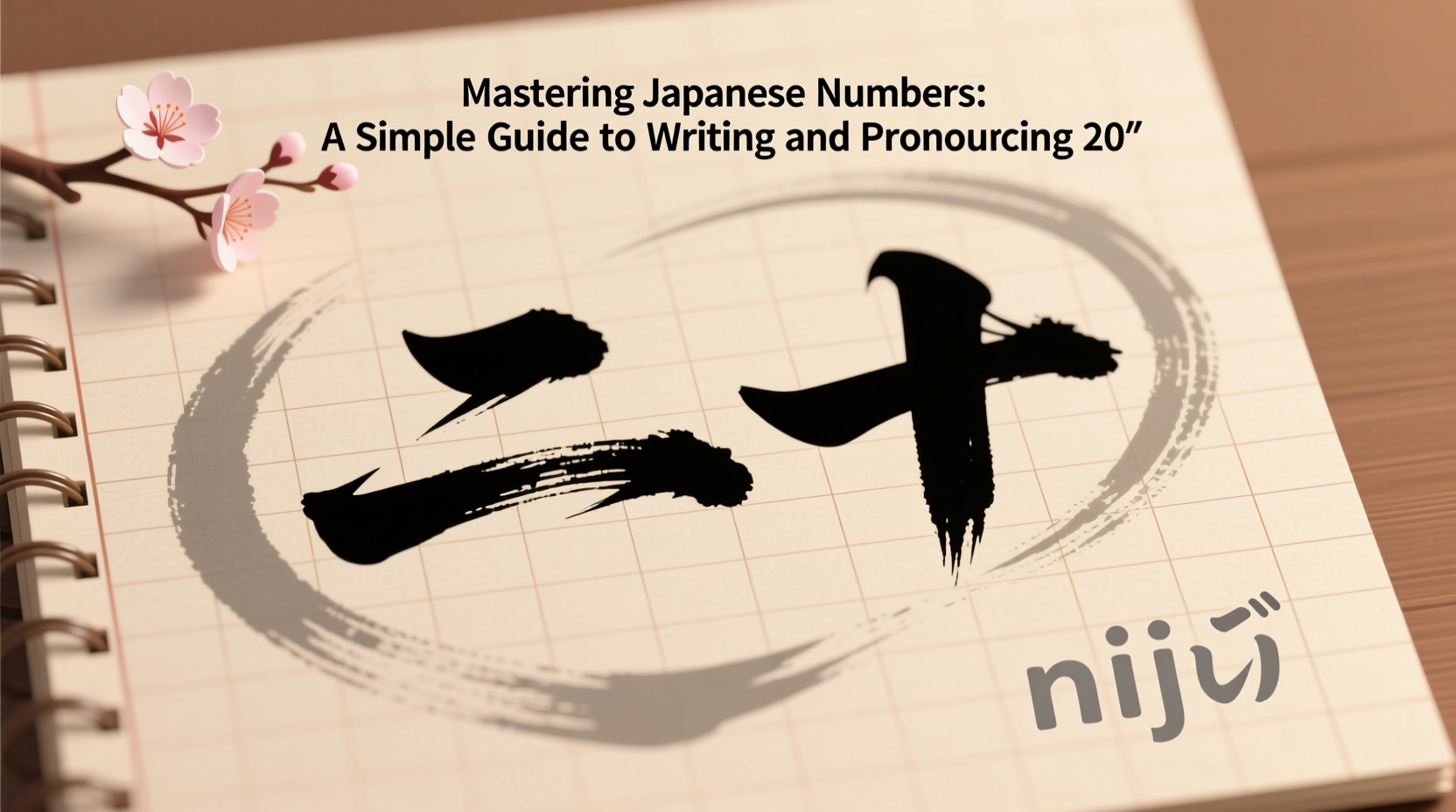

The kanji for 20 is 二十. It’s written with the character 二 (two) followed by 十 (ten). This structure mirrors the mathematical logic behind the number—two times ten.

While nijū is standard, there is a less common native reading: はたち (hatachi). This form is used almost exclusively to express someone’s age when they turn 20. In Japan, 20 is the legal age of adulthood, so this special reading carries cultural weight.

Understanding the Two Readings: Nijū vs. Hatachi

The distinction between nijū and hatachi reflects a deeper feature of the Japanese language: context-driven vocabulary. Most numbers use Sino-Japanese readings in general counting, but certain life events trigger native readings.

For example:

- You would say にじゅうさい (nijū-sai) when stating an age above 20, such as 21 or 25.

- But you say はたち (hatachi) only when referring to being exactly 20 years old.

This exception exists because turning 20 is a significant rite of passage in Japan. It's the age when individuals gain the right to vote, drink alcohol, and smoke legally. The Coming of Age Day (Seijin no Hi), celebrated on the second Monday of January, honors new adults who turned 20 in the past year.

“Hatachi isn’t just a number—it’s a social transformation. Using it properly shows respect for Japanese cultural norms.” — Dr. Akiko Tanaka, Linguist at Osaka University

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Learners often make predictable errors when dealing with 20 in Japanese. Awareness of these pitfalls can accelerate mastery.

| Mistake | Correct Form | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Saying \"ni-jū\" when talking about age 20 | Use \"hatachi\" | \"Nijū-sai\" sounds unnatural; \"hatachi\" is the culturally appropriate term. |

| Pronouncing \"jū\" like \"ju\" | Pronounce \"jū\" with a long \"u\" sound | \"Jū\" rhymes with \"shoe\"; the vowel is held longer than in English \"juice.\" |

| Writing 十二 instead of 二十 | Twenty is 二十, twelve is 十二 | Kanji order matters: number + ten, not ten + number. |

Mini Case Study: A Student’s Experience

Rina, an American studying abroad in Kyoto, confidently told her host family she was “nijū-sai” during introductions. Her host mother gently corrected her, saying, “Ah, hatachi? Omedetō gozaimasu!” (Oh, 20? Congratulations!). Rina later learned that using “nijū-sai” stripped away the celebratory nuance. After that, she began using “hatachi” in conversations about age and noticed people responded more warmly—often asking about her plans for adulthood. This small linguistic shift opened doors to deeper cultural connection.

Step-by-Step Guide to Mastering 20 in Japanese

Follow this five-step process to internalize both forms of 20 and use them appropriately.

- Learn the Kanji: Practice writing 二十 repeatedly. Focus on correct stroke order and spacing.

- Practice Pronunciation: Repeat “nijū” slowly: “nee-jyoo.” Then practice “hatachi”: “ha-ta-chee.” Record yourself and compare with native audio.

- Differentiate Contexts: Use flashcards with prompts like “How old are you if you're 20?” (Answer: hatachi) vs. “What’s 2 x 10?” (Answer: nijū).

- Listen for Usage: Watch Japanese dramas or news clips. Note when speakers use “hatachi” during birthday scenes or adulthood announcements.

- Speak in Real Situations: Introduce yourself using both forms: “Watashi wa hatachi desu” (I am 20 years old) or “Kore wa nijū-en desu” (This is 20 yen).

Expanding Beyond 20: Building Number Fluency

Once you’ve mastered 20, extending to higher numbers becomes intuitive. Japanese numbers follow a logical pattern up to 99:

- 21: 二十一 (nijū-ichi)

- 22: 二十二 (nijū-ni)

- 30: 三十 (sanjū)

- 40: 四十 (yonjū)

- 50: 五十 (gojū)

Note the irregularity in “four”—it’s “yon” instead of “shi” because “shi” means “death” and is avoided for superstition.

When counting objects, counters change pronunciation. For example:

- 20 books: 本二十冊 (hon nijū-satsu)

- 20 people: 二十人 (nijū-nin)

The key is consistency. Practice daily with real-world applications: counting money, telling time, or reading dates.

FAQ

Can I always use “nijū” instead of “hatachi”?

No. While grammatically understandable, using “nijū-sai” for age 20 sounds awkward and misses cultural significance. Reserve “hatachi” for age references only.

Is “hatachi” written differently?

No, “hatachi” is typically written in hiragana (はたち) or katakana (ハタチ), not kanji. Even though it means “twenty,” it doesn’t use 二十 in writing when referring to age.

Why does Japanese have two number systems?

Japanese inherited Chinese numerals (Sino-Japanese) for formal and mathematical use, while retaining native numbers (kun’yomi) for smaller counts and special cases like age, time, and traditional expressions.

Checklist: Mastering 20 in Japanese

Use this checklist to track your progress:

- ☐ Can write 二十 correctly with proper stroke order

- ☐ Can pronounce “nijū” and “hatachi” clearly

- ☐ Knows when to use “hatachi” (age 20) vs. “nijū” (all other contexts)

- ☐ Understands cultural significance of turning 20 in Japan

- ☐ Can count from 20 to 30 using correct patterns

- ☐ Has practiced in conversation or writing

Conclusion

Mastering the number 20 in Japanese is more than memorizing a word—it’s stepping into the rhythm of the language and culture. Whether you’re traveling, preparing for a JLPT exam, or connecting with Japanese friends, getting “nijū” and “hatachi” right shows attention to detail and respect for nuance. These small victories build confidence and pave the way for fluency. Start using both forms today, embrace the cultural context, and watch your Japanese grow stronger one number at a time.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?