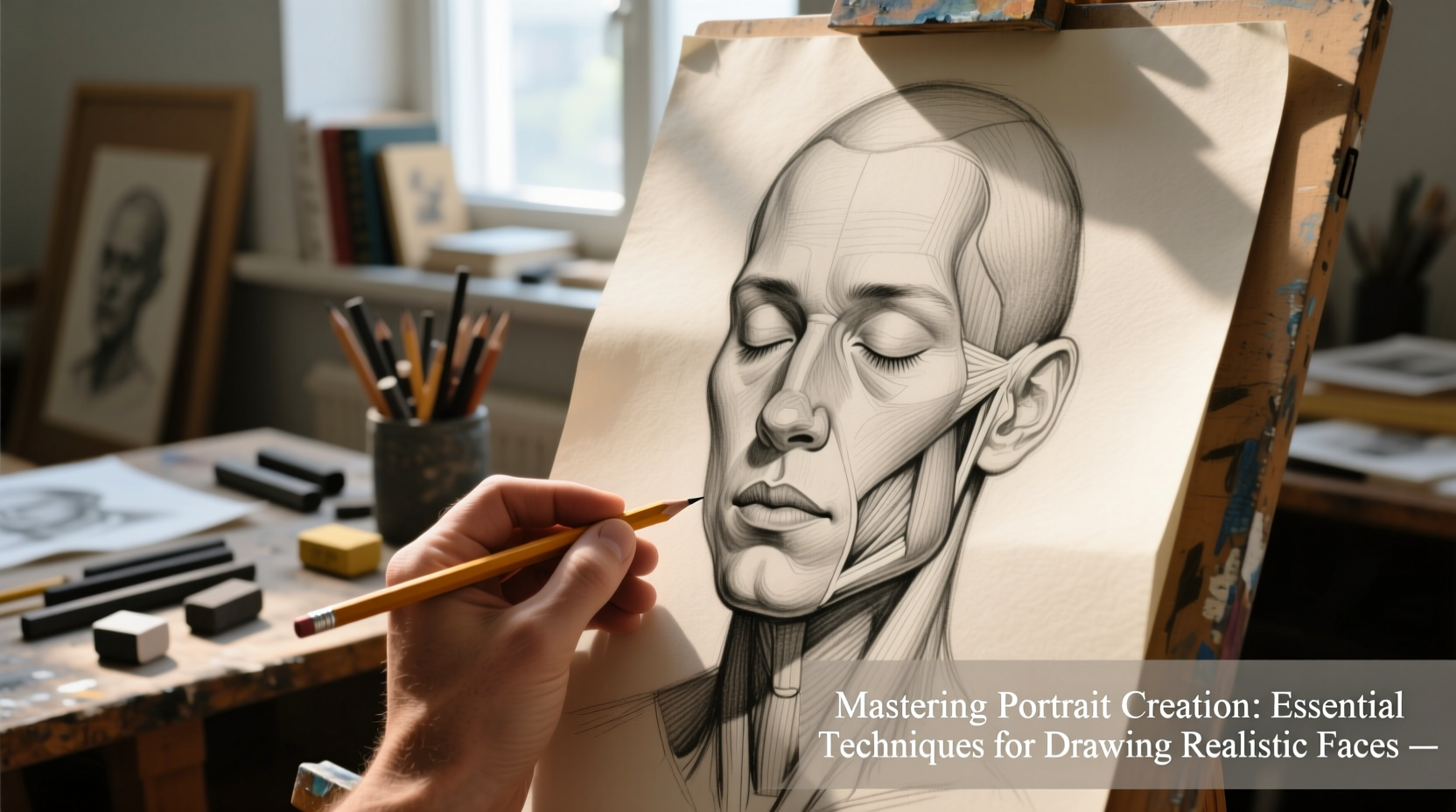

Drawing a realistic face is one of the most rewarding yet challenging skills in visual art. Unlike abstract or stylized forms, portraits demand accuracy in proportion, attention to subtle anatomical details, and sensitivity to light and shadow. Whether you're an aspiring artist or refining your craft, mastering the fundamentals of facial structure and rendering can elevate your work from amateur sketches to compelling likenesses.

The human face carries identity, emotion, and story. Capturing that essence requires more than just copying features—it involves understanding how bone structure, muscle movement, and lighting interact to form what we perceive as realism. This guide breaks down the core techniques that professional artists use to create lifelike portraits, step by step.

Anatomy of the Face: Proportions and Guidelines

Before adding detail, every strong portrait begins with accurate proportions. The face follows consistent spatial relationships across individuals, which serve as reliable reference points. One widely used method is the “Loomis head” technique, developed by illustrator Andrew Loomis, which helps artists construct the head in three-dimensional space.

Begin by drawing a circle for the cranium and a jawline extending downward. Divide the face vertically into five equal sections—each roughly the width of one eye. Horizontally, two key lines are critical: the first at mid-face level marks the position of the eyes, and a second, halfway between there and the chin, locates the base of the nose. The mouth typically sits one-third of the way up from the chin to the nose line.

| Facial Feature | Standard Position (Adult) |

|---|---|

| Eyes | Horizontal midpoint of the head |

| Nose | From eye line to mouth line; length = distance between eyes |

| Mouth | One-third up from chin to nose base |

| Ears | Align from eye line to nose base |

| Brow ridge | Above eye sockets, forming forehead curve |

These measurements vary slightly with age and individual differences—children have larger eyes relative to their face, and some ethnic features shift these norms—but they provide a dependable starting framework.

Constructing Depth with Light and Shadow

Realism emerges not just from shape but from volume. A flat outline lacks dimension; it’s the interplay of light and dark that gives the illusion of roundness and depth. Understanding value—the scale from white to black—is essential.

Observe where the primary light source hits the face. Highlight areas like the forehead, cheekbones, and tip of the nose will be brightest. Shadows gather under the brow, along the side of the nose, beneath the lower lip, and under the jawline. The transition between these zones should be gradual, avoiding harsh edges unless describing sharp contours like a defined chin.

“Value does all the work; color gets all the credit.” — Frank Reilly, renowned art instructor

Start with a mid-tone wash or hatching across the entire face. Then build shadows incrementally using crosshatching or blending tools. Reserve the paper's original tone for highlights, or lift graphite with a kneaded eraser. Avoid pressing too hard too soon—build contrast gradually to maintain control.

Step-by-Step Guide: Rendering a Realistic Eye

- Sketch the almond-shaped outline, noting tilt and overlap with surrounding features.

- Draw the iris and pupil within the visible portion of the eye socket.

- Add the upper and lower eyelids, remembering the upper lid usually covers part of the iris.

- Shade the pupil darkest, then the iris with radial strokes mimicking fiber patterns.

- Include reflection spots (catchlights) on the cornea to simulate wetness and life.

- Render subtle creases above the lid and soft shadow below the lower lid.

- Blend gently around the socket, deepening tone near the nose bridge.

Capturing Likeness and Expression

A technically perfect face may still lack soul if it doesn’t reflect personality. Likeness comes from subtle asymmetries—slightly different eye shapes, uneven brows, or a crooked smile—that make each person unique. Study reference photos closely, comparing left and right sides.

Expression alters everything. When someone smiles, the cheeks rise, crow’s feet appear, and the eyes narrow. A frown pulls the corners of the mouth down and creates vertical lines between the eyebrows. To draw convincing expressions, understand the underlying muscles: the zygomaticus major lifts the lips, while the corrugator supercilii furrows the brow.

Mini Case Study: From Sketch to Portrait

Sophia, a self-taught artist, struggled for months with inconsistent results. Her early attempts were either too stiff or distorted. After studying cranial anatomy and practicing grid-based proportioning, she began using timed studies (15–30 minutes) focusing only on alignment. She then layered longer sessions emphasizing tonal gradation. Within six weeks, her portraits gained structural confidence. By incorporating mirrored reference comparisons—flipping her drawing horizontally—she caught asymmetrical errors instantly. Today, her work captures both accuracy and emotional presence.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Overworking early stages: Don’t add texture or fine lines before establishing correct proportions.

- Ignoring negative space: Use gaps between features (e.g., eye to nose) as measuring tools.

- Flat shading: Lack of mid-tones flattens the face. Build values slowly.

- Copying details instead of observing shapes: Focus on overall masses before refining eyelashes or pores.

“The secret to drawing faces is seeing them as forms, not features.” — Juliette Aristides, author of *Classical Drawing Atelier*

Checklist: Essential Steps for Every Portrait Session

- Choose a high-resolution reference photo or live model.

- Lightly sketch basic head shape and center line.

- Mark horizontal guidelines for eyes, nose, and mouth.

- Plot feature positions using comparative measurement.

- Refine outlines with anatomical awareness.

- Establish light source and block in major shadow shapes.

- Develop mid-tones and transitions; preserve highlights.

- Define edges—soft for curves, sharp for contrasts.

- Review by flipping drawing or viewing in mirror.

- Add final details like hair strands, skin texture, and catchlights.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I make my portraits look less \"flat\"?

Flatness often results from insufficient value range. Ensure you’re using true blacks and clean whites, with smooth gradients in between. Also, check that your light source is consistent across all features. Adding ambient occlusion—darker tones in crevices like nostrils or under the chin—can enhance depth.

Should I draw hair first or last?

Always draw hair last. It surrounds and frames the face but shouldn’t interfere with structural development. Premature focus on locks distracts from proportion and tonal balance. Once the face is complete, render hair as overlapping planes of value, not individual strands.

Can I use a grid method effectively?

Yes, especially for beginners. The grid method divides reference and paper into squares, allowing precise transfer of shapes. While some purists avoid it, it trains the eye to see angles and distances accurately. Use it as a learning tool, then gradually rely on freehand observation.

Conclusion: Bring Your Portraits to Life

Mastering portrait creation isn’t about perfection—it’s about progress through disciplined observation and practice. Each face you draw teaches something new: how bone structure influences surface form, how emotion reshapes symmetry, and how light breathes life into graphite. These techniques are not shortcuts but foundational skills that compound over time.

Pick up your pencil today and commit to one focused study per week. Use mirrors, photos, and live subjects. Analyze master drawings. Compare, correct, and continue. With patience and purpose, you’ll move beyond mere representation to capturing the quiet humanity behind every pair of eyes.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?