Understanding the key of a song is foundational for musicians, producers, and composers. Whether you're transcribing music, improvising a solo, or preparing for a live performance, knowing the correct key allows you to play confidently and harmonize effectively. Yet, many struggle with this skill—not because it's inherently difficult, but because they lack a structured approach. This guide breaks down the process into clear, actionable steps that work whether you're working by ear, analyzing sheet music, or using digital tools.

The Importance of Knowing a Song’s Key

The key of a song defines its tonal center—the note and scale around which the melody and harmony revolve. It determines which chords sound natural together, guides vocalists in choosing comfortable ranges, and enables seamless modulation between sections. Without identifying the key accurately, attempts at playing along or reharmonizing can result in dissonance or confusion.

For example, if a guitarist tries to improvise over a song in D major using an E minor pentatonic scale, the notes will clash unless carefully navigated. Conversely, knowing the key allows immediate access to compatible scales, chord progressions, and melodic motifs.

“Ear training isn’t about perfect pitch—it’s about recognizing relationships. The key is often revealed not by one note, but by how notes move and resolve.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Music Cognition Researcher, Berklee College of Music

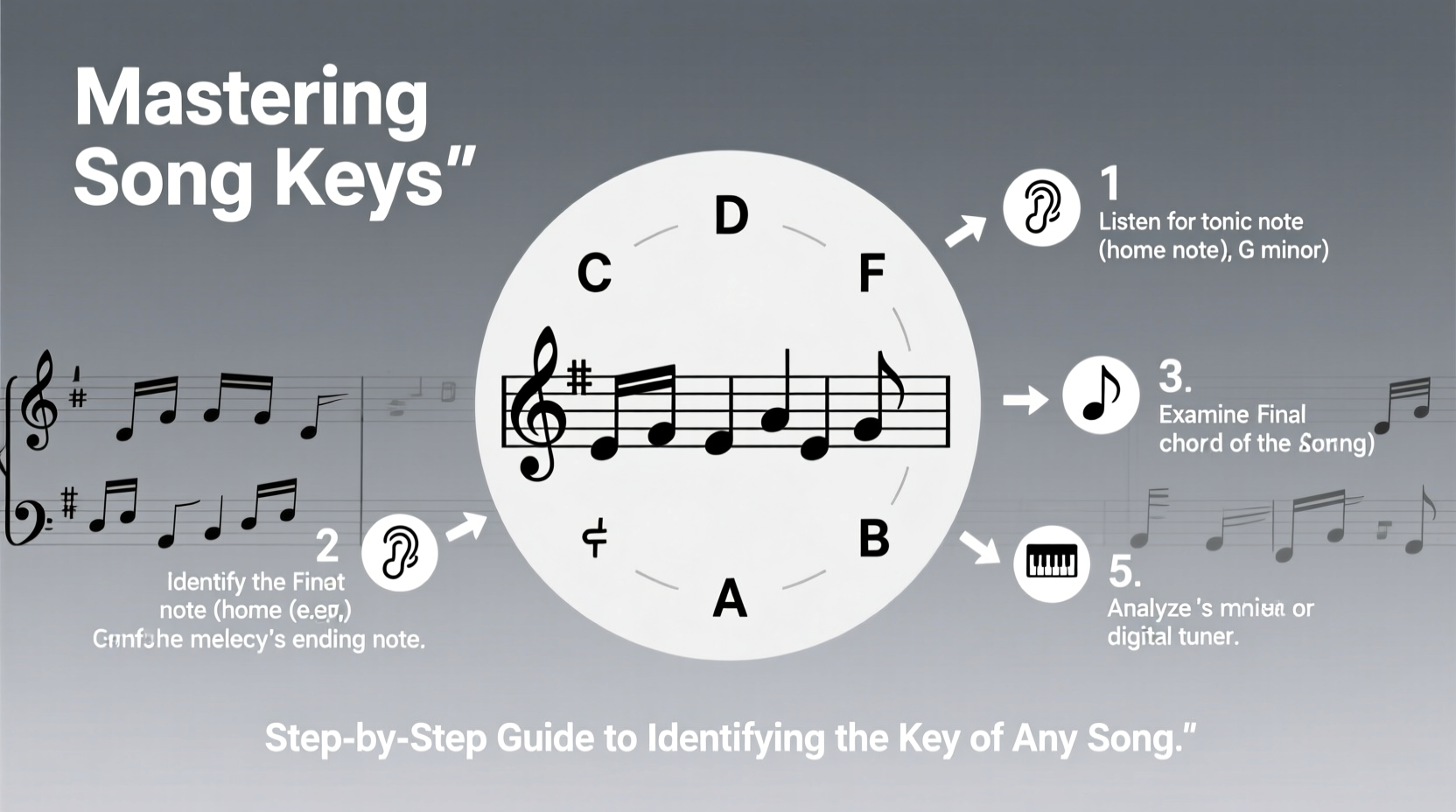

Step-by-Step Guide to Identifying a Song’s Key

Step 1: Listen for the Tonal Center (Home Note)

Play the song and focus on where the music feels most resolved—where phrases end comfortably. This \"home\" note is typically the tonic, the root of the key. Try humming or singing the last note of the melody; more often than not, it lands on the tonic.

If the song ends on a chord, identify that chord. Songs commonly conclude with the I chord (the tonic chord). For instance, if the final chord sounds like C major and the entire piece feels anchored to C, you may be in C major.

Step 2: Determine Major or Minor

Once you suspect a tonic, decide whether the mode is major or minor. Major keys sound bright and stable; minor keys feel darker or more introspective.

Listen to the primary chords used throughout the song. Does the tonic chord sound happy (major) or sad (minor)? Compare common progressions:

- Major: I–IV–V–I (e.g., C–F–G–C)

- Minor: i–iv–V–i (e.g., Am–Dm–E–Am)

Step 3: Identify the Scale Notes

After establishing a possible tonic and mode, map out the notes being used. Are sharps or flats present? Play suspected notes on an instrument and compare them to what you hear.

For example, if you’re analyzing a song centered on A and notice frequent use of C natural, E, and G, but no C# or G#, the scale likely contains C natural—pointing toward A minor rather than A major.

Step 4: Check for Accidentals and Modulations

Some songs shift keys temporarily (modulation) or borrow chords from parallel modes (modal mixture). If certain chords seem “out of place,” such as a sudden D major in C major, consider whether it leads to another key (like G major) or functions as a secondary dominant.

Pay attention to chromatic passing chords or pivot chords—they often signal a key change. However, don’t mistake borrowed chords for a full modulation.

Step 5: Confirm with Chord Progression Analysis

List the main chords in the song and assign Roman numerals based on your assumed key. In a true key, most chords should fit neatly within the diatonic set (seven chords built from the scale).

For instance, in G major, expected chords include G (I), Am (ii), Bm (iii), C (IV), D (V), Em (vi), and F#dim (vii°). If your progression uses mostly these chords, especially emphasizing I, IV, and V, your key identification is likely correct.

Practical Tools and Techniques

You don’t need perfect pitch to find a song’s key. Modern tools and systematic listening strategies make the process accessible to all musicians.

Use Digital Audio Software

DAWs like Ableton Live, Logic Pro, or free tools like Audacity can slow down audio without changing pitch. Use spectrum analyzers or pitch detection plugins (such as Melodyne or Scaler 2) to visualize prominent frequencies and suggest possible keys.

However, always verify automated suggestions with your ears—software can misinterpret complex harmonies or polyphonic textures.

Apply the Circle of Fifths

The circle of fifths organizes keys by their number of sharps or flats. If you determine a song uses one sharp (F#), it’s likely either G major or E minor—relative keys sharing the same key signature.

| # of Sharps/Flats | Key Signature | Possible Keys |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | No sharps/flats | C major / A minor |

| 1 sharp (F#) | G major | G major / E minor |

| 2 flats (Bb, Eb) | Bb major | Bb major / G minor |

| 3 sharps (F#, C#, G#) | A major | A major / F# minor |

| 1 flat (Bb) | F major | F major / D minor |

Mini Case Study: Finding the Key of “Let It Be” by The Beatles

Consider “Let It Be.” The song begins and ends with a C major chord. The verse uses C–G–Am–F, a classic I–V–vi–IV progression in C major. The melody emphasizes C, E, and G, reinforcing the tonic triad. There are no sharps or flats in the basic chord set.

Although Am appears frequently, it functions as a vi chord, not the tonic. The resolution back to C after each phrase confirms C as the tonal center. Therefore, the key is C major.

This analysis combines auditory cues, harmonic function, and structural repetition—a reliable method applicable to thousands of pop and rock songs.

Checklist: How to Confirm a Song’s Key

- ✅ Listen for the final chord or resolving note

- ✅ Hum or sing the tonic pitch

- ✅ Determine if the mood is major (bright) or minor (dark)

- ✅ List all chords and check against a suspected key

- ✅ Verify that the I, IV, and V chords appear frequently

- ✅ Use the circle of fifths to cross-reference key signatures

- ✅ Test your conclusion by playing the relative scale over the track

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Misidentifying the key often stems from confusing the starting chord with the tonic. Some songs begin on the IV or V chord for dramatic effect. For example, “Smells Like Teen Spirit” opens with a F5 power chord, but the tonal center is actually B♭ major (or G minor, depending on interpretation)—not F.

Another issue arises with modal interchange or borrowed chords. A song in C major might use an E♭ major chord (borrowed from C minor). Don’t assume the key has changed—look at context and resolution patterns.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a song be in more than one key?

Yes. Many songs modulate (change key) between sections. For example, a bridge might shift up a half-step for emotional intensity. Identify the primary key first, then note any secondary keys used temporarily.

What if the song doesn’t use traditional chords?

In atonal or experimental music, there may be no clear key. Focus instead on recurring pitches or drones. Ambient or electronic tracks might center on a single note or use synthetic modes outside standard major/minor systems.

Do all songs have a key?

Most Western popular music does—but not all. Some genres, like free jazz or noise music, deliberately avoid tonality. In such cases, describe the texture or pitch clusters instead of assigning a key.

Conclusion

Identifying the key of a song is a blend of intuition, theory, and practice. With consistent listening, analytical thinking, and the right tools, anyone can develop this essential musical skill. Start with simple songs, confirm your findings on an instrument, and gradually take on more complex pieces. Over time, your ability to hear tonal centers and harmonic movement will sharpen naturally.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?