Duck calling is more than just making noise—it’s an essential skill in waterfowl hunting that mimics the natural vocalizations of ducks to attract them within range. For beginners, the sound of a properly executed call can seem elusive. But with consistent practice and the right technique, anyone can learn to produce realistic quacks, feed calls, and hail sounds. This guide breaks down the fundamentals of blowing a duck call, offering clear steps, actionable tips, and insights from seasoned hunters to help you build confidence and accuracy.

Understanding Duck Call Components

Before producing sound, it's important to understand how a duck call works. Most modern duck calls consist of three main parts: the barrel, the insert (or tone board), and the reed. Air blown through the mouthpiece vibrates the reed against the tone board, creating sound. The pitch, volume, and tone are influenced by airflow, tongue placement, and throat control—not force.

There are two primary types of duck calls: single-reed and double-reed. Double-reed calls are generally easier for beginners because they require less precise breath control. Single-reed calls offer more tonal variation but demand greater finesse.

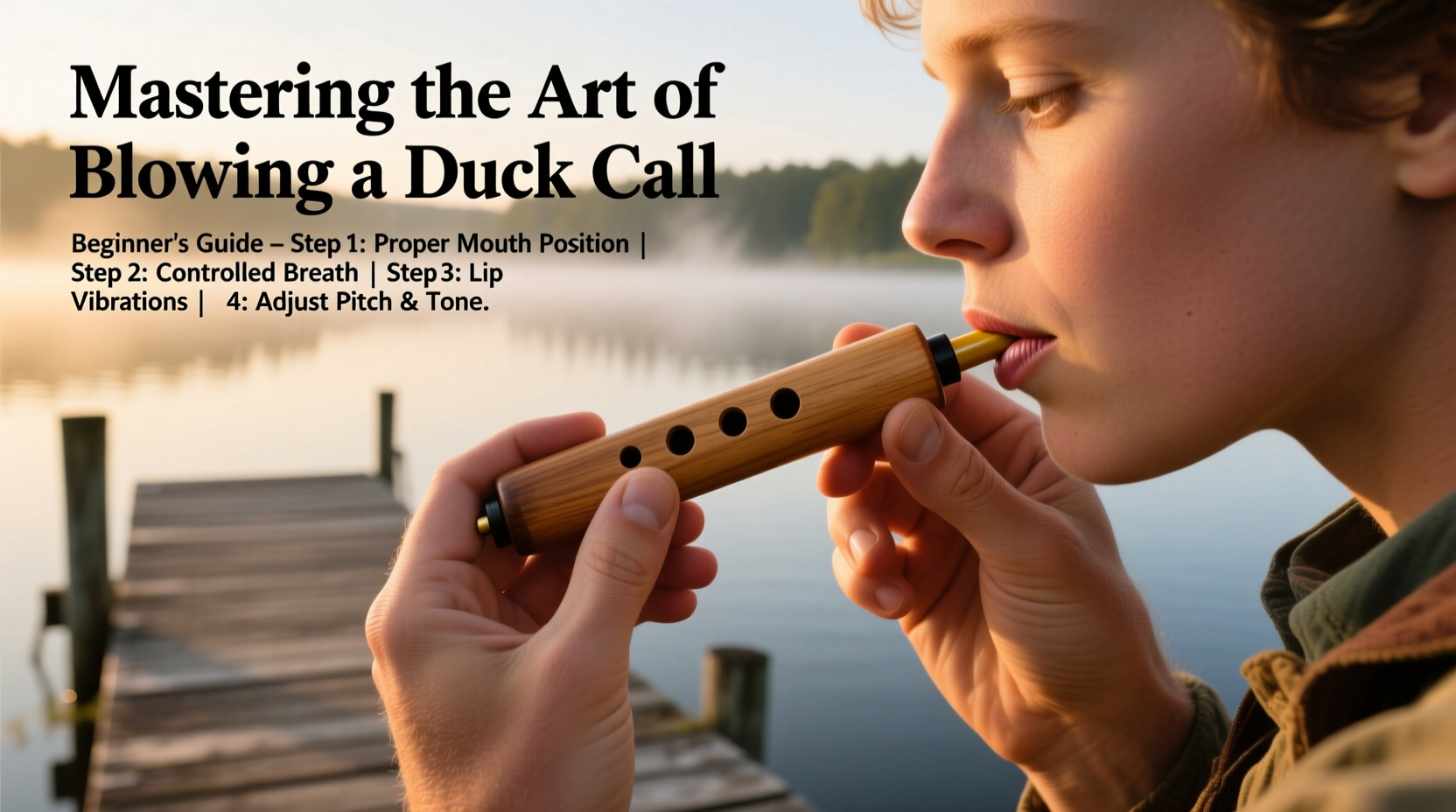

Step-by-Step Guide to Blowing Your First Duck Call

Producing your first realistic duck sound doesn’t happen overnight, but following a structured approach accelerates progress. Here’s a proven sequence to develop foundational skills.

- Hold the call correctly: Grip the call between your thumb and fingers, keeping your hand relaxed. Don’t squeeze tightly—this restricts airflow and dampens tone.

- Position your lips: Place your lips slightly over the mouthpiece, forming a small “O” shape. Avoid pressing hard; let the call rest gently against your lips.

- Breathe from your diaphragm: Use controlled, steady air from your abdomen—not your throat or chest. Think of fogging a mirror with warm breath.

- Start with a soft “k” sound: Say the word “book” silently, focusing on the “k” at the end. Use this motion to cut off air abruptly and create a clean note.

- Practice the single quack: Inhale, then say “quack” using your throat and tongue, not your vocal cords. The sound should be short and sharp: “ka-hit.”

- Adjust tone with your tongue: Raise the back of your tongue for higher pitches, lower it for deeper tones. Small adjustments make big differences.

At first, expect inconsistent or squeaky sounds. This is normal. Focus on smooth airflow and crisp articulation rather than volume.

Common Beginner Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Many new callers struggle with the same pitfalls. Recognizing these early prevents bad habits from forming.

| Mistake | Why It’s a Problem | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Blowing too hard | Causes screeching, kills tone control | Use gentle, steady air; focus on tongue stops |

| Using vocal cords | Makes sound unnatural and strained | Breathe through call without voice—like whispering |

| Gripping too tightly | Blocks resonance and airflow | Relax hand; hold call lightly |

| Ignoring ear training | Leads to unrealistic sounds | Listen to live ducks or recordings daily |

Essential Duck Calls Every Beginner Should Master

Once you can produce a consistent quack, expand your repertoire. These three calls form the core of duck calling strategy.

- The Feed Call: A rapid series of soft, irregular quacks (“dak-dak-dak-dak”) simulating ducks feeding. Use during lulls to maintain interest.

- The Comeback Call: A loud, high-pitched five-note hail (“kee-kee-kee-koo-quit!”) used to grab distant ducks’ attention.

- The Decoy Puddle Call: A medium-volume, rhythmic 3-note quack (“quack-quack-quack”) to reassure approaching birds.

Mini Case Study: From Squeaks to Success

Mark, a first-time hunter from Arkansas, struggled for weeks with his duck call. Every attempt resulted in squeals or silence. He recorded himself and compared it to a recording of wild mallards. The difference was stark. Instead of blowing harder, he focused on relaxing his jaw and using his tongue to stop air cleanly. Within two weeks of daily 10-minute sessions, he produced a clean, rolling feed call. On his third hunt, a group of greenheads turned mid-flight and landed 30 yards out—drawn in by his newfound realism.

Expert Insight: What the Pros Emphasize

“Less is more in duck calling. A soft, well-timed quack beats a loud, poorly placed one every time. Ducks respond to confidence in sound, not volume.” — Dale DeSantis, National Duck Calling Champion

DeSantis, who has won multiple state and national competitions, stresses that timing and context matter as much as technique. “Call when ducks are looking. Stop when they commit. Realism isn’t just about sound—it’s about behavior.”

Checklist: Building Your Duck Calling Routine

Consistency turns effort into instinct. Use this checklist to structure your practice.

- ✅ Choose a beginner-friendly double-reed acrylic call

- ✅ Practice 10–15 minutes daily, even off-season

- ✅ Record yourself weekly to track improvement

- ✅ Listen to live duck sounds daily (apps or online audio)

- ✅ Focus on clean tongue stops, not forceful blowing

- ✅ Master the single quack before advancing to sequences

- ✅ Use minimal hand pressure—keep grip relaxed

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take to learn duck calling?

With regular practice, most beginners produce recognizable quacks within 1–2 weeks. Achieving realistic, effective calling typically takes 2–3 months of consistent effort. Mastery, however, is a lifelong pursuit shaped by experience in the field.

Should I use a triple-reed call as a beginner?

Triple-reed calls offer rich tone but require advanced breath and tongue control. They’re best suited for intermediate to advanced callers. Beginners should start with double-reed models for better consistency and ease of use.

Can I use a duck call without hunting?

Absolutely. Many people practice duck calling as a hobby or competitive sport. Events like the Memphis Jim Stafford Classic celebrate precision and realism, independent of hunting. It’s a unique blend of artistry and tradition.

Final Tips for Long-Term Success

Like any instrument, a duck call improves with care. Rinse the mouthpiece occasionally with warm water and let it air dry. Store it in a protective case away from extreme temperatures. Over time, reeds wear out—replace them when tone becomes flat or inconsistent.

Also, remember that patience is part of the craft. Ducks are intelligent; they detect hesitation and repetition. Vary your cadence, pause often, and observe bird behavior. The best callers aren’t the loudest—they’re the ones who listen first.

“The best duck caller in the blind is the one who knows when *not* to call.” — Traditional Waterfowl Wisdom

Conclusion: Take the First Quack

Learning how to blow a duck call opens a deeper connection to nature and the traditions of waterfowl hunting. It demands discipline, ear training, and humility—but the reward is unmistakable: the moment a flock responds to a call you made with your own breath and intention. Start simple, stay consistent, and embrace the learning curve. With each practice session, you’re not just making noise—you’re speaking the language of the marsh.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?