Mustard seeds are among the most widely used spices in global cuisine, prized for their pungent aroma, sharp flavor, and transformative effect when heated. From Indian curries to German sausages, these tiny seeds play a pivotal role in building depth and complexity in dishes. Despite their small size, mustard seeds carry significant culinary weight—offering not just heat but also nuttiness, bitterness, and a distinctive floral note when properly tempered. Understanding the differences between varieties, their optimal applications, and proper handling techniques allows cooks to harness their full potential. This guide explores every facet of mustard seeds, from botany to pantry, equipping home chefs and professionals alike with actionable knowledge for consistent, flavorful results.

Definition & Overview

Mustard seeds come from several species within the Brassica and Sinapis genera, primarily Brassica juncea, B. nigra, and Sinapis alba. These small, round seeds are harvested from flowering plants related to cabbage, broccoli, and radish. When whole, they are hard and relatively inert in flavor; however, upon exposure to moisture, heat, or grinding, enzymatic reactions release volatile compounds—most notably allyl isothiocyanate—that produce their signature sharpness and heat.

The use of mustard seeds dates back over 5,000 years, with early records in Indian, Roman, and Chinese culinary traditions. In ancient India, they were valued both as food and medicine, while Romans ground them into pastes mixed with wine to accompany meats—laying the foundation for modern prepared mustards. Today, mustard seeds remain integral to pickling, tempering, spice blends, and condiment production across continents.

Culinarily, mustard seeds function as both a seasoning and a flavor catalyst. They are rarely eaten raw due to their intense bitterness but become aromatic and complex when cooked correctly. Their ability to bloom in oil makes them ideal for foundational techniques such as *tadka* (tempering) in South Asian cooking, where they form the base layer of flavor in dals, chutneys, and vegetable stir-fries.

Key Characteristics

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Flavor Profile | Pungent, sharp, slightly bitter, with nutty undertones when toasted. Heat intensity varies by type. |

| Aroma | Peppery and earthy when raw; becomes warm, toasted, and floral when heated in oil. |

| Color & Form | Yellow/tan (white), brown, or black. Small, spherical seeds (1–2 mm diameter). |

| Heat Level | Varies: white mildest, black hottest. Heat develops only when hydrated or heated. |

| Culinary Function | Base flavor builder, emulsifier in pickles, textural element, source of pungency. |

| Shelf Life | Whole seeds: 3–4 years in cool, dark place. Ground loses potency within 6–12 months. |

| Solubility Trigger | Enzyme myrosinase activated by water, heat, or crushing—releases sinigrin-derived pungency. |

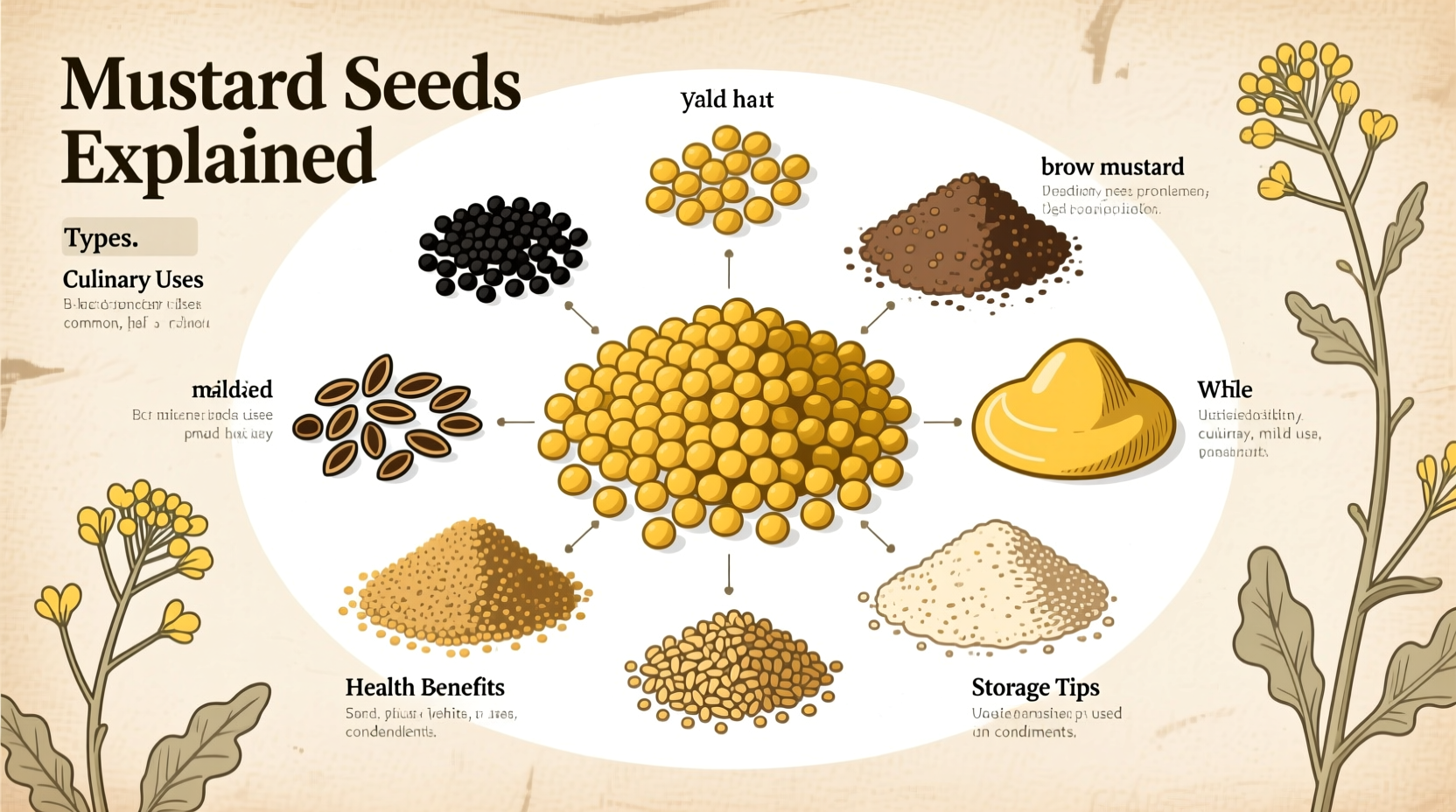

Variants & Types

Not all mustard seeds are created equal. Three primary types dominate global markets, each differing in origin, heat level, and preferred application.

White (or Yellow) Mustard Seeds – Sinapis alba

Despite the name, these seeds range from pale yellow to light tan. Native to the Mediterranean, they are the mildest of the three, producing a subtle heat that develops slowly. White mustard seeds contain sinalbin, a glucosinolate that yields less pungency than those found in darker varieties.

They are commonly used in American-style yellow mustard, pickling brines, and beer-based sauces. Their milder profile makes them suitable for long-cooked dishes where sustained heat without overpowering sharpness is desired.

Brown Mustard Seeds – Brassica juncea

Brown mustard seeds are the workhorse of Indian, Nepali, and Bangladeshi kitchens. Slightly smaller and darker than white seeds, they pack more heat and complexity. Derived from *B. juncea*, they contain sinigrin—the compound responsible for intense pungency when activated by moisture or heat.

These seeds are essential in tempering (*tadka*) for dals, sambar, and chutneys. They pop and crackle when heated in oil, releasing a deep, nutty aroma. Brown mustard is also used in Dijon-style mustards and Chinese hot mustards, often combined with vinegar to modulate sharpness.

Black Mustard Seeds – Brassica nigra

True black mustard seeds are rare in commercial cultivation today due to harvesting difficulties, but they remain prized in traditional South Indian and Ethiopian cooking. Smaller and darker than brown seeds, they deliver the most intense heat and fragrance. Once fully tempered, they develop a rich, almost floral depth unmatched by other types.

In Tamil Nadu and Kerala, black mustard seeds are used in coconut-based curries, rasam, and seasoned yogurt preparations. Because of their volatility, they require careful temperature control—too little heat yields raw bitterness; too much burns them instantly.

TIP: If you can't find true black mustard seeds, substitute with brown mustard seeds and add a pinch of nigella (kalonji) for aromatic complexity. The flavor won’t be identical, but it approximates the layered warmth expected in regional Indian dishes.

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Mustard seeds are often confused with other small, dark seeds or mistaken for ground mustard. Clarifying distinctions ensures accurate usage.

| Ingredient | Differences from Mustard Seeds |

|---|---|

| Nigella Seeds (Kalonji) | Smaller, matte black, crescent-shaped. Earthy, onion-like flavor. No pungency. Often used alongside mustard seeds but never interchangeable. |

| Sesame Seeds | Oval, ivory-to-brown. Nutty-sweet when toasted. Lack any heat. Used for texture and richness, not pungency. |

| Fenugreek Seeds | Yellowish-brown, angular, bitter-sweet. Burn easily. Used in moderation for background bitterness in curry blends. |

| Ground Mustard / Mustard Powder | Pre-ground version. Reacts instantly with liquid to create heat. More convenient but less stable; loses potency faster than whole seeds. |

| Poppy Seeds | Gray-blue, tiny, starchy. Mild, nutty, no heat. Used for thickening and texture, especially in North Indian gravies. |

\"The difference between a good dal and a great one often lies in the precision of the tempering. Mustard seeds must sizzle, not smoke. That moment of controlled popping unlocks layers you can't achieve with powder.\" — Chef Anjali Pathak, Culinary Director, Spice Heritage Institute

Practical Usage: How to Use Mustard Seeds in Cooking

Proper technique determines whether mustard seeds enhance or ruin a dish. Their power lies not in quantity but in timing and method.

Tempering (Tadka / Chaunk)

This foundational technique involves heating whole spices in oil or ghee to extract flavor before adding to a finished dish or base sauce. For mustard seeds:

- Heat neutral oil (such as sunflower or peanut) or ghee in a pan over medium heat.

- Add 1–2 tsp mustard seeds depending on serving size.

- Wait until seeds begin to pop—this indicates internal moisture turning to steam.

- Once 70–80% have popped (about 20–30 seconds), immediately add complementary spices like cumin, asafoetida, or dried chilies.

- Pour the infused oil and seeds over dals, steamed vegetables, or yogurt raita.

Delaying this step causes burning; removing too early leaves them underdeveloped. Mastery comes from recognizing the auditory cue: a soft crackling sound signals readiness.

Pickling & Brining

Mustard seeds contribute both flavor and preservative qualities in pickles. In vinegar-based brines, they absorb acidity while releasing mild heat and body. Common in bread-and-butter pickles, sauerkraut, and Indian lime or mango achar, they are typically combined with turmeric, fenugreek, and chili.

For best results, lightly toast seeds before packing jars to deepen flavor and reduce microbial load. Whole seeds maintain integrity during fermentation, unlike ground versions which may cloud the brine.

Condiments & Sauces

From French Dijon to Chinese hot mustard, the transformation of seeds into paste relies on controlling enzyme activity. To make homemade mustard:

- Grind brown or yellow seeds coarsely or finely based on texture preference.

- Mix with cold liquid (water, vinegar, beer, wine) to activate enzymes gradually.

- Allow to rest 10–30 minutes for full pungency development.

- Add honey, salt, or spices to balance heat.

Using warm liquid deactivates myrosinase, resulting in milder flavor. Vinegar halts the reaction entirely—ideal for sweet mustards needing tang without burn.

Baking & Marinades

Crushed mustard seeds act as a binder and flavor carrier in rubs for meats, particularly pork and lamb. Mixed with oil, garlic, and herbs, they form a crust that seals in juices during roasting. In artisanal breads, especially rye or sourdough, soaked mustard seeds add texture and a savory counterpoint to fermented dough.

PRO TIP: Soak brown mustard seeds in apple cider vinegar overnight for sandwich spreads. Blend with mayonnaise and a touch of maple syrup for a house-made honey mustard with superior depth and shelf stability.

Pairing Suggestions & Ratios

Successful pairing depends on balancing mustard seed’s sharpness with complementary ingredients:

- Legumes: Use 1 tsp brown mustard seeds per cup of lentils. Pairs exceptionally well with urad dal and toor dal.

- Vegetables: Green beans, eggplant, spinach, and potatoes respond well to mustard tempering. Add a pinch of turmeric and fresh curry leaves for authenticity.

- Dairy: Stir tempered mustard into plain yogurt for instant raita. Combine with cucumber, mint, and roasted cumin.

- Meats: Rub crushed seeds onto beef brisket or lamb shoulder before slow-roasting. Enhances bark formation and adds complexity.

- Liquids: Pair with coconut milk, tamarind, lemon juice, and tomato—acidity tempers heat and brightens finish.

Storage & Shelf Life

To preserve potency, store whole mustard seeds in an airtight container away from light, heat, and moisture. A dark cupboard or refrigerator drawer works best. Properly stored, they retain flavor for up to four years.

Ground mustard deteriorates rapidly due to increased surface area. Grind only what’s needed using a mortar and pestle or spice grinder. Pre-ground “mustard powder” should be used within six months of opening.

Freezing is unnecessary for whole seeds but viable for long-term storage in humid climates. Avoid storing near strong-smelling foods—seeds can absorb odors.

Substitutions & Limitations

No direct substitute replicates the unique behavior of whole mustard seeds, but alternatives exist for specific contexts:

- For tempering: None. Skip or replace with cumin if allergic. Toasted sesame offers texture but not flavor equivalence.

- For mustard paste: Prepared mustard (Dijon, stone-ground) at 1:1 ratio. Adjust for salt and vinegar content.

- For pickling: Mustard powder at half the amount (½ tsp powder = 1 tsp seeds). Note: powder clouds brine faster.

- Allergy considerations: Mustard is a recognized allergen in the EU and Canada. Cross-reactivity with cruciferous vegetables possible. Substitute with celery seeds or fennel for aromatic lift.

Practical Tips & FAQs

Can I eat mustard seeds raw?

Technically yes, but not advisable. Raw seeds are extremely bitter and difficult to digest. Enzymatic pungency can irritate the stomach lining in sensitive individuals. Always cook or hydrate before consumption.

Why do my mustard seeds burn so quickly?

Mustard seeds have low thermal tolerance. Medium-high heat is sufficient. Use oils with high smoke points (peanut, safflower), and never leave unattended. Once they start popping, proceed immediately to next step.

Do different colors mean different ripeness?

No. Color reflects species, not maturity. White, brown, and black are distinct botanical types, not stages of growth. Mixing them does not increase heat linearly—each contributes its own flavor dimension.

Can I grow my own mustard seeds?

Yes. All three types grow readily in temperate climates. Plant in early spring; harvest pods when dry and brown. Requires minimal care, attracts pollinators, and doubles as a cover crop to suppress weeds.

Are organic mustard seeds worth the premium?

For whole spices, yes. Organic certification reduces risk of pesticide residue and irradiation (used to sterilize imported spices). Given mustard seeds are consumed whole and unpeeled, sourcing clean stock matters.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Mustard seeds are far more than a condiment ingredient—they are a dynamic, foundational spice capable of defining entire dishes. Understanding the differences between white, brown, and black varieties empowers cooks to choose the right seed for the right purpose. Brown seeds dominate everyday Indian cooking due to their balance of heat and aroma; black seeds offer unmatched intensity for specialty preparations; white seeds provide mild, reliable pungency in Western-style mustards and pickles.

The key to success lies in technique: tempering requires attention to heat levels and timing, while hydration controls the development of pungency. When used correctly, mustard seeds build depth, stimulate appetite, and harmonize with legumes, vegetables, dairy, and meats alike.

Store whole seeds properly to maximize shelf life, avoid substitutions unless necessary, and respect their potency. Whether crafting a simple dal tadka or fermenting homemade sauerkraut, mustard seeds remain an indispensable tool in the global pantry.

Next time you reach for the spice jar, consider the journey of those tiny seeds—from ancient fields to your kitchen—and let their crackle in hot oil remind you that great flavor begins with intention.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?