Oceanic trenches are among the most dramatic features of Earth’s seafloor—deep, narrow furrows where the planet’s crust bends and plunges into the mantle. While trenches exist in other oceans, over 70% of the world’s deepest ones are found in the Pacific. This concentration is no accident; it results from powerful geological forces unique to the region. Understanding why the Pacific hosts so many trenches requires a look at plate tectonics, subduction zones, and the dynamic nature of Earth’s lithosphere.

The Role of Plate Tectonics in Trench Formation

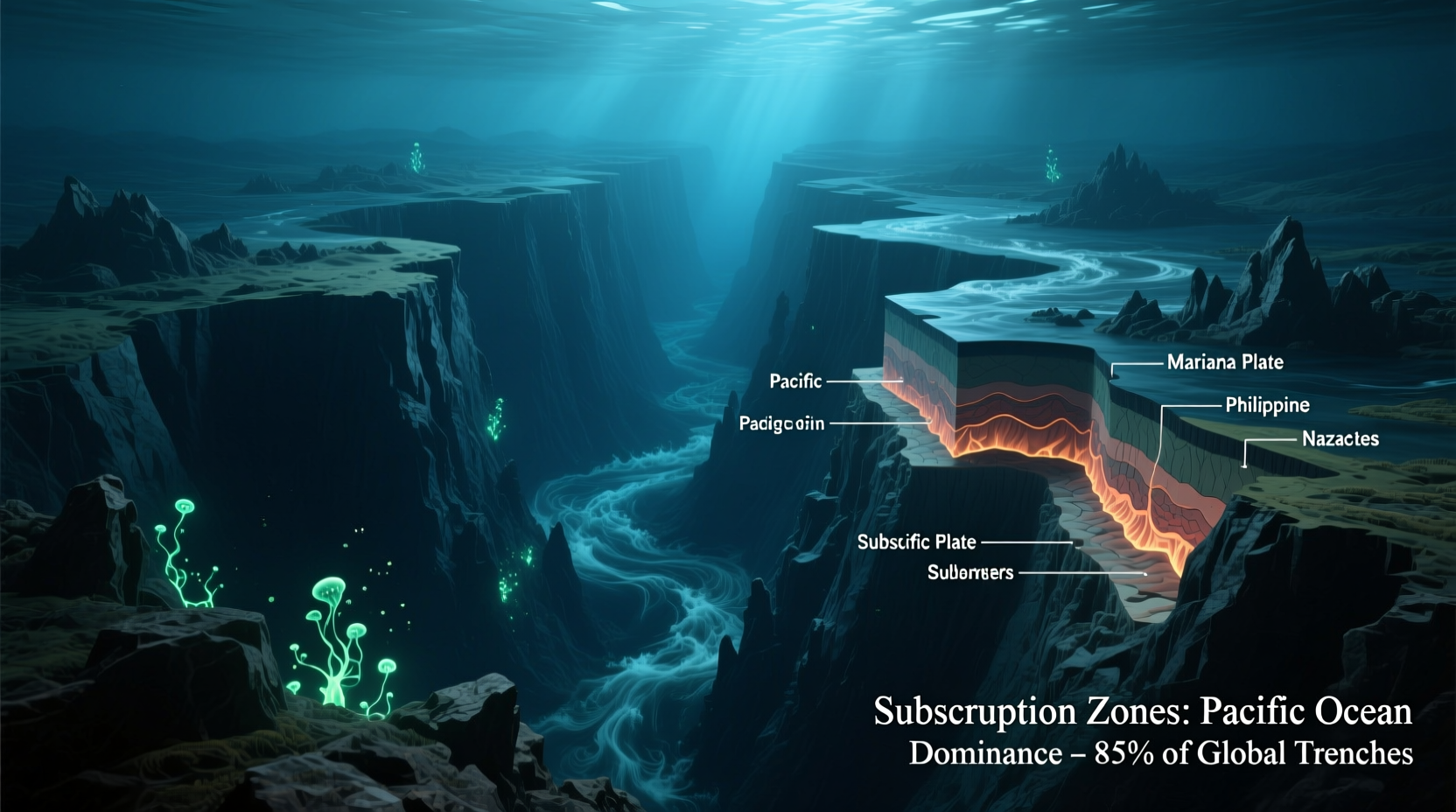

Oceanic trenches form primarily at convergent plate boundaries, where two tectonic plates collide. When an oceanic plate meets another plate—whether oceanic or continental—the denser oceanic plate typically sinks beneath the lighter one in a process called subduction. As it descends, it creates a deep depression on the seafloor: the trench.

The Pacific Ocean is surrounded by active plate boundaries, collectively known as the \"Ring of Fire.\" This horseshoe-shaped zone stretches from New Zealand, along the eastern edge of Asia, across the Bering Strait, down the west coast of North and South America, and back into the southern Pacific. It contains more than 45,000 miles of tectonically active margins, making it the most geologically restless region on Earth.

“Subduction zones are the engines behind the planet’s most profound topographic features—and the Pacific has more of them than any other ocean.” — Dr. Linda Chen, Geophysicist, Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Why the Pacific Dominates in Trench Density

The Pacific Ocean sits atop the remnants of an ancient supercontinent and its surrounding seafloor is dominated by dense, old oceanic crust. Unlike the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, which are still expanding due to mid-ocean ridges pushing plates apart, the Pacific is slowly shrinking. This contraction increases compressive stress around its edges, promoting subduction.

Several key factors explain the high concentration of trenches in the Pacific:

- Abundance of oceanic-oceanic convergence: Many Pacific trenches form where one oceanic plate dives beneath another, such as the Mariana Trench (Pacific Plate under Philippine Sea Plate).

- Continental margins with active subduction: Along western South and North America, the oceanic Nazca and Juan de Fuca plates subduct beneath continental plates, forming trenches like the Peru-Chile Trench.

- Age and density of Pacific plates: Older oceanic crust is colder and denser, making it more likely to sink. Much of the Pacific seafloor is over 100 million years old, ideal for subduction.

- Encircled by destructive margins: While the Atlantic has passive margins (like the U.S. East Coast), the Pacific rim is almost entirely made of active, convergent boundaries.

Major Pacific Oceanic Trenches and Their Depths

The Pacific is home to nearly all of the world’s trenches exceeding 10,000 meters in depth. Below is a comparison of notable Pacific trenches:

| Trench | Location | Maximum Depth (meters) | Formed By |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mariana Trench | Western Pacific, east of Philippines | 10,984 | Pacific Plate subducting under Philippine Sea Plate |

| Tonga Trench | Southern Pacific, near Fiji | 10,882 | Indo-Australian Plate under Pacific Plate |

| Kuril-Kamchatka Trench | Northwest Pacific, near Russia | 10,500 | Pacific Plate under Okhotsk Plate |

| Peru-Chile Trench | Eastern Pacific, off South America | 8,065 | Nazca Plate under South American Plate |

| Japan Trench | East of Japan | 8,427 | Pacific Plate under Okhotsk Plate |

This table highlights not only the dominance of the Pacific but also the variety of tectonic interactions that generate these deep zones. The Mariana Trench, the deepest known point on Earth (Challenger Deep), exemplifies extreme subduction dynamics driven by rapid plate motion and old, dense lithosphere.

How Subduction Shapes Global Geology

Subduction doesn’t just create trenches—it drives much of Earth’s surface recycling. As oceanic plates descend, they carry water, sediments, and minerals into the mantle. This influx lowers the melting point of surrounding rock, generating magma that rises to form volcanic arcs. These arcs appear as island chains (like the Aleutians or the Marianas) or coastal mountain ranges (such as the Andes).

In this way, trenches are the starting points of a planetary recycling system. The Pacific’s numerous trenches mean it plays a central role in this cycle. Over millions of years, entire ocean basins have been consumed—evidence suggests the current Pacific may eventually close entirely, giving rise to a new supercontinent.

Mini Case Study: The 2011 Tohoku Earthquake and Japan Trench

The Japan Trench was the epicenter of one of the most powerful earthquakes in recorded history. In March 2011, a magnitude 9.0 quake occurred when the Pacific Plate suddenly slipped beneath the Okhotsk Plate. The seafloor uplift displaced massive volumes of water, triggering a devastating tsunami that struck northeastern Japan.

This event illustrates how trenches aren't just static depressions—they are zones of immense stored energy. Stress builds over decades as plates lock together, then releases catastrophically during megathrust earthquakes. Monitoring these regions helps scientists forecast seismic hazards and improve early warning systems.

Checklist: Key Factors Behind Pacific Trench Concentration

To summarize the primary reasons most oceanic trenches are in the Pacific, consider the following checklist:

- ✅ Surrounded by active convergent boundaries (Ring of Fire)

- ✅ High number of subduction zones due to plate configuration

- ✅ Presence of old, dense oceanic crust favorable for sinking

- ✅ Ongoing compression causing basin shrinkage

- ✅ Frequent interaction between oceanic and continental plates

- ✅ Long history of tectonic activity increasing trench development

Frequently Asked Questions

Are there any major trenches outside the Pacific?

Yes, though fewer and generally shallower. The Puerto Rico Trench in the Atlantic (depth ~8,376 m) and the Java Trench (Sunda Trench) in the Indian Ocean (~7,290 m) are notable exceptions. However, none match the depth or number of Pacific trenches.

Can new trenches form in the Atlantic Ocean?

Currently, the Atlantic is expanding due to seafloor spreading at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. There are no active subduction zones large enough to form deep trenches. However, some geologists predict that in 100–200 million years, as the Atlantic begins to close, trenches could develop along its margins.

Do oceanic trenches affect marine life?

Absolutely. Despite extreme pressure and darkness, trenches host unique ecosystems. Microorganisms thrive on chemicals from subducted materials, supporting specialized species like amphipods and snailfish. These habitats offer insights into life’s adaptability and potential analogs for extraterrestrial environments.

Conclusion: A Window Into Earth’s Inner Workings

The abundance of oceanic trenches in the Pacific Ocean is a direct result of the region’s unparalleled tectonic activity. From the Mariana to the Tonga and Peru-Chile trenches, these deep scars mark where Earth’s crust is being continuously recycled. They serve as natural laboratories for studying earthquakes, volcanism, and the long-term evolution of our planet.

Understanding why the Pacific dominates in trench formation isn’t just about geography—it reveals how dynamic and interconnected Earth’s systems truly are. By studying these depths, scientists gain insight into the forces that shape continents, trigger disasters, and sustain life in even the most extreme conditions.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?