Sesame seeds—tiny, oil-rich, and profoundly flavorful—are among the oldest cultivated oilseed crops in human history. Their global journey spans continents, cultures, and millennia, yet few understand where they truly originate or how geography shapes their character. For home cooks, bakers, and culinary professionals alike, knowing the origin of sesame seeds isn’t just a matter of curiosity—it influences taste, aroma, texture, and even nutritional value in dishes ranging from tahini to sushi rolls. The region where sesame is grown affects everything from seed size to oil content, making geographic sourcing a critical factor in both traditional and modern cuisine.

Understanding the cultivation patterns, dominant growing regions, and agricultural conditions behind sesame seeds empowers consumers to make informed choices. Whether you're selecting seeds for a Middle Eastern dip, an East Asian stir-fry, or a European bread recipe, origin matters. This article explores the historical roots of sesame cultivation, maps its current global production landscape, and explains how terroir—the unique combination of soil, climate, and farming practices—shapes the final product on your plate.

Definition & Overview

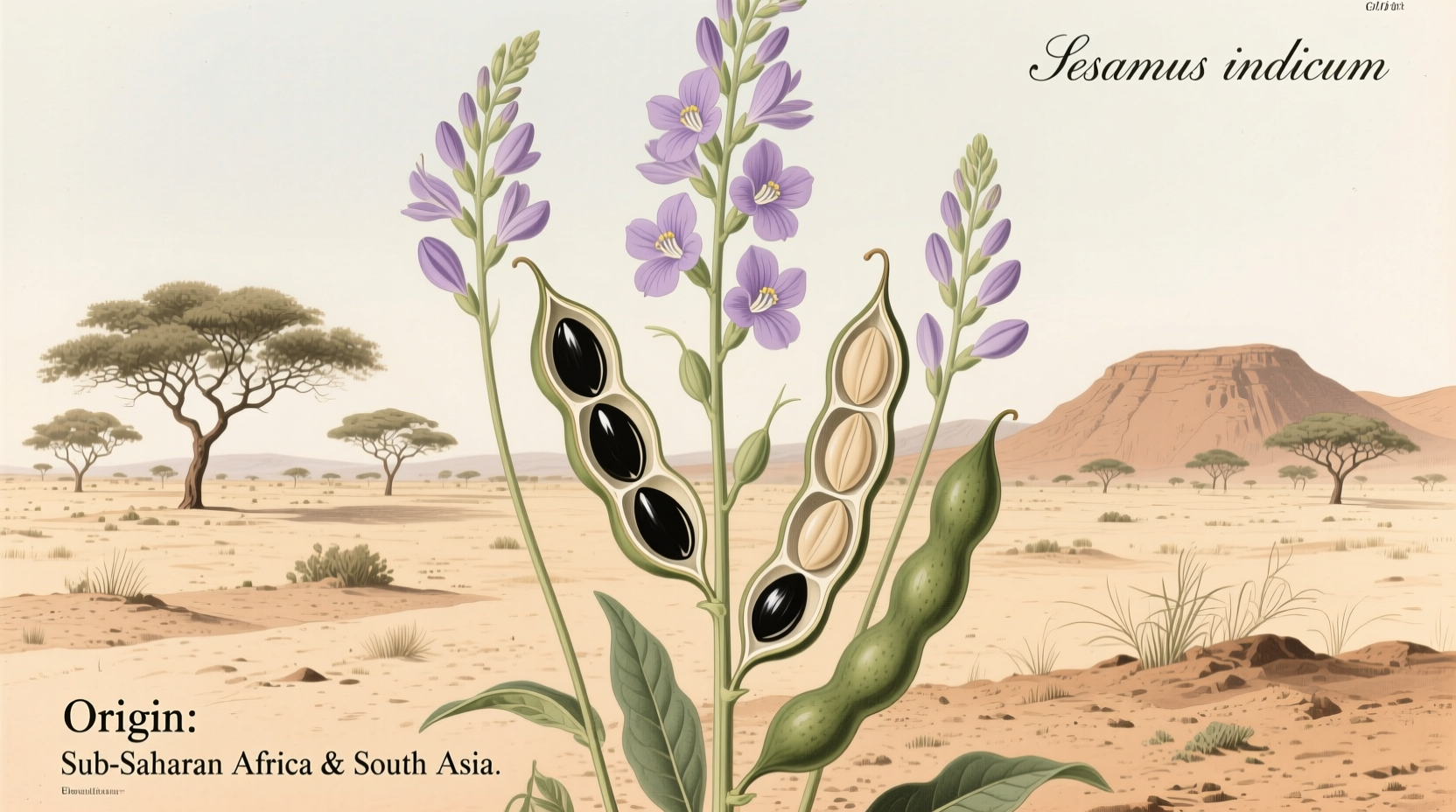

Sesame (Sesamum indicum) is an annual flowering plant native to tropical regions of Africa and possibly India. Its seeds, enclosed in pods that burst open when ripe (a trait known as dehiscence), have been harvested for over 5,000 years. These small, flat oval seeds range in color from ivory white and golden tan to deep brown and black, each variety offering distinct flavor profiles and culinary applications.

The plant thrives in warm climates with well-drained soils and requires a long, hot growing season—typically 90 to 130 days. Despite being drought-tolerant compared to many crops, it is sensitive to waterlogging and performs best under consistent heat. Historically, sesame was prized not only for its edible seeds but also for its high oil yield, which can reach up to 60% by weight, making it one of the most oil-dense natural sources available before modern extraction methods.

Culturally, sesame holds symbolic significance across civilizations. In ancient Egypt, it was associated with immortality; in Hindu mythology, it represents spiritual purity; and in West African traditions, it plays a role in ceremonial foods. Today, it remains integral to cuisines worldwide—from Japanese goma-dare (sesame sauce) to Ethiopian kinfe (spiced sesame paste)—but its modern supply chain traces back to a handful of key producing nations.

Key Characteristics of Sesame Seeds

- Flavor Profile: Nutty, slightly sweet, with a rich umami depth when toasted. Black sesame has a more intense, earthy bitterness compared to milder white varieties.

- Aroma: Subtle raw scent; develops a roasted, buttery fragrance upon heating.

- Color Variants: White (hulled), golden, brown, red, and black (usually unhulled).

- Oil Content: Among the highest of all oilseeds—typically between 45% and 60%, depending on cultivar and growing conditions.

- Shelf Life: Up to 1 year unopened in cool, dark storage; shorter once exposed to air due to oxidation of oils.

- Culinary Function: Used as seasoning, garnish, thickener (in sauces and pastes), base for oils and dairy-free alternatives, and binder in vegetarian cooking.

- Heat Sensitivity: Low smoke point (~350°F/177°C); best used raw, lightly toasted, or blended into emulsions rather than deep-fried at high temperatures.

TIP: Toasting sesame seeds enhances flavor dramatically. Spread them in a dry skillet over medium-low heat for 2–4 minutes, stirring constantly until fragrant and lightly golden. Cool completely before storing or using.

Where Are Sesame Seeds Grown? Global Production Map

Sesame cultivation today is concentrated in tropical and subtropical zones across Asia, Africa, and parts of South America. While wild relatives of sesame exist in sub-Saharan Africa, the domesticated form spread early to South Asia, becoming deeply embedded in Indian agriculture and Ayurvedic tradition. Over centuries, trade routes carried sesame eastward to China and Japan and westward through the Arab world into the Mediterranean.

Modern commercial production is dominated by several countries, each contributing unique varietals shaped by local agronomy and consumer demand. As of recent FAO and USDA data, the top producers include:

| Country | Annual Production (Metric Tons) | Primary Growing Regions | Dominant Seed Type | Culinary Use Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myanmar (Burma) | ~1.3 million | Mandalay, Magway, Sagaing | White, golden | Export-oriented; preferred for neutral-flavored oils and international markets |

| Sudan | ~800,000 | Kordofan, Gedaref | White, light brown | Traditional consumption; major exporter to Middle East and Europe |

| India | ~750,000 | Gujarat, Rajasthan, Telangana | White, off-white, black | Domestic spice blends (tahini, til laddoo), temple offerings, street food |

| Tanzania | ~300,000 | Dodoma, Singida | Brown, red-husked | Local porridges, chutneys; growing export presence in EU organic markets |

| Burkina Faso | ~250,000 | Central Plateau, Cascades | Brown, black | West African stews (e.g., maafe), fermented pastes |

| China | ~600,000 | Anhui, Hubei, Jiangxi | Black, white | Toasted pastes, medicinal foods, confectionery (mooncakes) |

| Uganda | ~200,000 | Northern Region | White, cream | Fresh grinding for sauces; increasing Fair Trade exports |

This distribution reflects both agroclimatic suitability and economic infrastructure. Countries like Myanmar and Sudan lead due to vast arid plains ideal for low-input farming, while smaller producers such as Uganda focus on niche, traceable supply chains appealing to ethical buyers.

Variants & Types by Region and Processing

While all sesame seeds come from the same species, processing and regional breeding have led to significant variation in appearance, taste, and function. Understanding these types helps match the right seed to the right dish.

By Color and Hulling Status

- White (Hulled): Most common in Western supermarkets. Outer hull removed, revealing pale kernel. Milder flavor, higher oil yield. Ideal for tahini, dressings, and baking where visual neutrality matters.

- Golden/Tan: Partially hulled or naturally lighter. Slightly more robust than white, often used in Japanese and Korean cuisine.

- Brown: Retains some hull material. Earthier taste, used in rustic breads and traditional African dishes.

- Black: Unhulled, with dark pigment from anthocyanins. Stronger, slightly bitter note. Central to Chinese medicine and desserts like black sesame soup.

- Red: Rare outside East Africa and parts of India. Husk has reddish tint; often ground into specialty flours.

By Form and Preparation

- Raw Whole Seeds: Untreated, shelf-stable. Best for controlled toasting at home.

- Toasted/Pan-Roasted: Pre-heated to develop flavor. Common in Asian grocery products.

- Crushed or Ground: Used in spice mixes (e.g., za’atar), halva, or as thickening agent.

- Paste (Tahini): Stone-ground sesame butter. Consistency varies by region—Middle Eastern tahini is smooth and pourable; Ethiopian versions may be coarser.

- Oil: Cold-pressed or refined. High in antioxidants like sesamol, giving it excellent oxidative stability.

\"In Ethiopia, we don’t just grow sesame—we live with it. From the morning injera dipped in kinfe to evening prayers where sesame oil lights the lamp, it connects us to land and spirit.\" — Abebe Tesfaye, Agronomist, Addis Ababa University

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Sesame seeds are sometimes confused with other small, oily seeds, especially given overlapping uses in baking and garnishing. However, key differences exist in flavor, nutrition, and behavior during cooking.

| Ingredient | Size/Texture | Flavor | Oil Content | Cooking Behavior | Common Confusion With Sesame? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sesame Seed | Small, flattened oval; crunchy when toasted | Nutty, rich, becomes deeper when heated | 45–60% | Releases oil easily; browns quickly | Baseline |

| Poppy Seed | Smaller, rounder, grittier | Mild, faintly floral, less oily | 40–50% | Holds shape better in baked goods | Yes – similar appearance on bagels/breads |

| Chia Seed | Tiny, speckled, gel-forming when wet | Neutral, slightly grassy | 30–35% | Forms mucilage; absorbs liquid | Less so now, but often substituted incorrectly |

| Flaxseed | Oval, glossy, larger than sesame | Earthy, woody, must be ground for nutrient access | 40–45% | Does not toast as evenly; prone to rancidity | Rarely, but mistaken in granola mixes |

The most frequent confusion occurs between white sesame and poppy seeds in bakery applications. Visually similar on bread crusts or crackers, they differ significantly: poppy seeds add crunch without strong flavor contribution, whereas sesame contributes both texture and pronounced nuttiness. Substituting one for the other alters the sensory profile of the dish.

Practical Usage: How to Use Sesame Seeds in Cooking

Maximizing the potential of sesame seeds begins with understanding how their origin and form affect performance in recipes. Here’s how to apply them effectively across culinary contexts:

In Home Kitchens

- Tahini Preparation: Use hulled white or golden sesame seeds for smooth, mild tahini. Roast lightly first (do not burn), then blend with neutral oil (like sunflower) until creamy. Store refrigerated for up to 3 months.

- Stir-Fries and Noodles: Sprinkle toasted sesame seeds at the end of cooking for aroma and texture. Combine with soy sauce, rice vinegar, and ginger for instant umami boost.

- Baking: Incorporate into bread doughs (e.g., pita, naan, bagels) or sprinkle on top before baking. Black sesame adds visual drama to cookies and mochi.

- Salad Dressings: Whisk tahini with lemon juice, garlic, and water to create creamy vinaigrettes. Emulsifies well and clings to greens.

- Vegetable Coatings: Press raw or toasted seeds onto roasted vegetables (carrots, cauliflower) for added crunch and visual appeal.

In Professional and Restaurant Settings

- Infused Oils: Steep lightly crushed seeds in warm oil (below smoking point) for 20–30 minutes, then strain. Ideal for finishing grilled fish or drizzling over hummus.

- Signature Garnishes: Mix black and white sesame seeds for striking contrast on sushi or dim sum platters.

- Spice Blends: Include in dukkah (Egyptian mix), gomasio (Japanese sea salt-sesame blend), or berbere (Ethiopian spice mix, though less common).

- Plant-Based Cuisine: Use tahini as egg substitute (1 tbsp = 1 egg) in vegan baking or as base for dairy-free cheese sauces.

PRO TIP: For maximum flavor impact in sauces, grind sesame seeds just before use. A mortar and pestle works better than a spice grinder for retaining essential oils and avoiding overheating.

Practical Tips & FAQs

How should I store sesame seeds?

Keep in an airtight container in a cool, dark cupboard for up to 6 months. For longer storage (up to 1 year), refrigerate or freeze. Due to high polyunsaturated fat content, they oxidize quickly when exposed to light and heat.

Can I substitute tahini with peanut butter?

In emergencies, yes—but expect altered flavor and texture. Peanut butter is sweeter, thicker, and lacks the savory depth of tahini. Better substitutes include almond butter or sunflower seed butter for allergies.

Are black and white sesame seeds nutritionally different?

Yes. Black sesame retains its fibrous hull, providing more calcium, iron, and antioxidants (anthocyanins). White sesame, while lower in minerals, offers higher bioavailability of certain fats due to removal of phytic acid in the hull.

Why do some sesame seeds taste bitter?

Bitterness usually results from over-toasting or using old, rancid seeds. Black sesame naturally has a more assertive, slightly bitter edge, which balances well in sweet preparations like buns or puddings.

Is sesame gluten-free?

Yes, inherently. However, cross-contamination can occur in facilities that process wheat. Always check packaging if allergies are a concern.

What dishes showcase regional sesame styles best?

- Middle East: Hummus, falafel, ka'ak (sesame ring bread)

- East Asia: Gomashio, yaki onigiri, ma la tang (spicy broth with sesame oil)

- South Asia: Til chikki (jaggery-sesame brittle), thalipeeth (multigrain pancake)

- Africa: Benne wafers (West Africa), kinfe (Ethiopia), maafe (peanut-sesame stew)

- Mediterranean: Pasteli (Greek honey-sesame bar), soutzoukakia (spiced meatballs with sesame crust)

Summary & Key Takeaways

Sesame seeds are far more than a simple garnish—they are a cornerstone of global gastronomy with deep historical roots and diverse modern expressions. Origin plays a decisive role in their characteristics: seeds from Myanmar tend to be large and mild, ideal for mass-market oils; those from Ethiopia and Sudan offer bold, rustic flavors suited to traditional pastes; Chinese black sesame delivers medicinal richness prized in desserts and tonics.

The choice of sesame type—by color, hulling status, or preparation method—should align with the intended culinary outcome. Toasting unlocks depth, while proper storage preserves freshness. Understanding regional differences allows cooks to source intentionally, whether building authentic ethnic dishes or innovating with global flavors.

As demand grows for sustainably sourced, ethically produced ingredients, transparency in sesame supply chains becomes increasingly important. Look for certifications like Organic, Fair Trade, or Direct Trade when possible, particularly for African-grown varieties that support smallholder farmers.

Final Thought: Next time you sprinkle sesame on a bowl of ramen or stir tahini into a dressing, consider its journey—from ancient fields in Africa and India to your kitchen table. That tiny seed carries centuries of culture, craftsmanship, and climatic nuance worth savoring.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?