Acidity is a fundamental concept in organic chemistry, influencing reactivity, solubility, and biological activity. Among common organic compounds, phenols and alcohols both contain hydroxyl (–OH) groups, yet they exhibit striking differences in acidity. While alcohols are generally neutral or very weakly acidic, phenols are significantly more acidic—so much so that they react with strong bases like sodium hydroxide. Understanding this contrast isn’t just academic; it has real implications in synthesis, pharmaceutical design, and industrial processes.

The key lies not in the presence of the –OH group itself, but in how the surrounding molecular structure affects the stability of the conjugate base after deprotonation. This article explores the chemical basis for the acidity difference between phenols and alcohols, examines contributing factors such as resonance and hybridization, and provides practical insights into how these principles apply in real-world contexts.

Why Acidity Matters: The Role of the Conjugate Base

When evaluating acidity, chemists focus on the ease with which a compound donates a proton (H⁺). A stronger acid loses its proton more readily, forming a stable conjugate base. For both phenols and alcohols, deprotonation yields an alkoxide ion (RO⁻), but the stability of this ion varies dramatically depending on the structure.

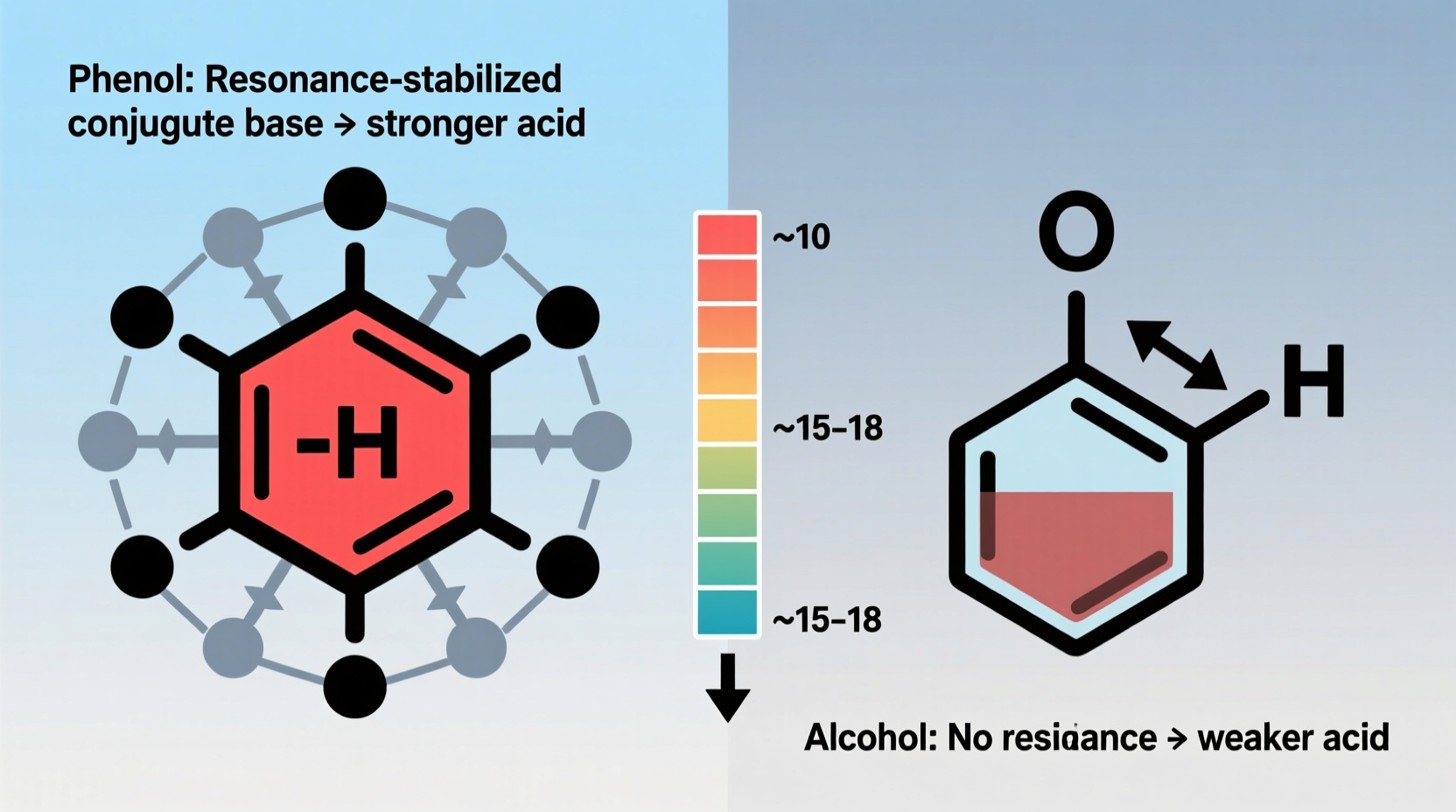

In alcohols, the conjugate base is an alkoxide (e.g., CH₃CH₂O⁻), where the negative charge is localized on the oxygen atom. This charge is not effectively stabilized, making the ion high in energy and thus less favorable to form. In contrast, when phenol loses a proton, it forms a phenoxide ion, where the negative charge is delocalized into the aromatic ring through resonance. This delocalization significantly lowers the energy of the conjugate base, making phenol far more willing to donate its proton.

“Resonance stabilization of the phenoxide ion is the single most important factor explaining why phenols are about a million times more acidic than typical alcohols.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Organic Chemistry Instructor, University of Michigan

Structural Differences: Resonance and Electron Delocalization

The benzene ring in phenol plays a crucial role in enhancing acidity. Upon deprotonation, the lone pair on the oxygen of the phenoxide ion overlaps with the π-system of the aromatic ring, allowing the negative charge to be shared across multiple atoms—specifically, at the ortho and para positions of the ring.

This resonance effect can be visualized through several contributing structures, where the negative charge alternates between the oxygen and carbon atoms in the ring. The resulting resonance hybrid spreads out the charge, increasing stability. No such stabilization occurs in alkoxides derived from aliphatic alcohols, where the charge remains confined to the oxygen.

Hybridization and Inductive Effects

Beyond resonance, other electronic factors contribute to the acidity gap. One such factor is the hybridization of the carbon attached to the oxygen. In phenol, the carbon bonded to the –OH group is sp²-hybridized due to its participation in the aromatic system. sp² orbitals have higher s-character (33%) compared to sp³ orbitals (25%), meaning they are closer to the nucleus and more electronegative.

This increased electronegativity pulls electron density away from the O–H bond, weakening it and facilitating proton release. In contrast, the carbon in ethanol (a typical alcohol) is sp³-hybridized and less effective at stabilizing negative charge through inductive withdrawal.

Additionally, substituents on the aromatic ring can further modulate phenol acidity. Electron-withdrawing groups (like –NO₂ or –CN) enhance acidity by stabilizing the phenoxide ion, while electron-donating groups (like –CH₃ or –OH) reduce it by increasing electron density on the ring.

Comparative Analysis: Phenols vs Alcohols

| Property | Phenols | Alcohols |

|---|---|---|

| pKa Range | 8–10 | 15–18 |

| Conjugate Base Stability | High (resonance-stabilized) | Low (charge localized) |

| Reaction with NaOH | Yes (forms water-soluble phenoxide) | No (no significant reaction) |

| Hybridization of C–OH Carbon | sp² | sp³ |

| Resonance in Conjugate Base | Yes | No |

| Effect of Electron-Withdrawing Groups | Increases acidity | Minor effect |

This table highlights the stark contrast between the two classes of compounds. The lower pKa values of phenols confirm their greater acidity—remember, lower pKa means stronger acid. The ability of phenols to react with NaOH is a simple laboratory test to distinguish them from alcohols.

Practical Implications in Synthesis and Industry

The acidity difference between phenols and alcohols is exploited routinely in organic synthesis. For example, selective deprotonation allows chemists to protect alcohols while reacting phenolic groups, or vice versa, depending on conditions. Phenol’s acidity also makes it useful in the production of polymers like Bakelite, antioxidants such as BHT, and pharmaceuticals including aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid).

In drug design, modifying phenolic groups can fine-tune solubility and bioavailability. Because phenoxides are more water-soluble than their protonated forms, adjusting pH can control whether a phenolic drug is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract or excreted.

Mini Case Study: Aspirin Synthesis

Salicylic acid, the precursor to aspirin, contains both a phenolic –OH and a carboxylic acid group. During acetylation, only the phenolic oxygen is targeted for esterification, leaving the carboxylic acid intact. This selectivity is possible because the phenolic group is more nucleophilic after mild deprotonation—something feasible due to its relatively low pKa (~10) compared to aliphatic alcohols (pKa ~16). If salicylic acid were replaced with an aliphatic diol, such selective modification would require much harsher conditions and protective group strategies.

Actionable Checklist: Identifying and Working with Phenols

- Test for acidity: Add a few drops of the compound to aqueous NaOH. If it dissolves, it may be a phenol.

- Compare pKa values: Use reference tables to estimate acidity based on structure and substituents.

- Assess resonance potential: Determine if the conjugate base can delocalize charge into an aromatic system.

- Consider substituent effects: Nitro groups at ortho/para positions increase acidity; alkyl groups decrease it.

- Use proper safety measures: Phenols can be corrosive and toxic—handle with gloves and in fume hoods.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can alcohols ever be as acidic as phenols?

Typical aliphatic alcohols cannot match the acidity of phenols due to lack of resonance stabilization. However, alcohols with strong electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., trifluoroethanol, pKa ~12.4) approach phenol-like acidity, though still less than most phenols.

Why doesn’t ethanol react with sodium hydroxide?

The conjugate base of ethanol (ethoxide) is too unstable to be formed in water. NaOH is not a strong enough base in aqueous solution to deprotonate ethanol significantly, as water (pKa 15.7) is a weaker acid than ethanol (pKa ~16). In contrast, phenol (pKa ~10) is a stronger acid than water, so the equilibrium favors deprotonation by NaOH.

Are all phenols equally acidic?

No. Substituents on the aromatic ring greatly affect acidity. For instance, picric acid (2,4,6-trinitrophenol, pKa ~0.4) is strongly acidic due to three nitro groups withdrawing electron density, while p-methylphenol (p-cresol, pKa ~10.2) is slightly less acidic than phenol itself.

Conclusion: Mastering the Principles Behind Acidity

The difference in acidity between phenols and alcohols is a perfect illustration of how molecular structure dictates chemical behavior. Resonance stabilization, hybridization, and inductive effects combine to make phenols uniquely acidic among hydroxyl-containing compounds. Recognizing these patterns empowers chemists to predict reactivity, design better molecules, and solve complex problems in research and industry.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?