Aircraft flaps are critical high-lift devices used during takeoff and landing to increase wing camber and surface area, enhancing lift at lower speeds. Among the earliest mechanical flap designs are plain and split flaps—both mechanically simple but functionally distinct. While both improve low-speed performance, they differ significantly in how they alter airflow, generate lift, and affect drag. Understanding which flap produces more lift isn’t just academic; it influences aircraft handling, runway requirements, and pilot decision-making.

This article examines the aerodynamics, efficiency, and practical implications of plain versus split flaps, backed by engineering principles and real-world flight dynamics. The goal is clear: determine which flap type delivers greater lift and under what conditions.

How Flaps Work: The Basics of Lift Enhancement

Lift is generated when air flows over a wing, creating a pressure differential between the upper and lower surfaces. At slow speeds—such as during approach or takeoff—this pressure difference diminishes, increasing the risk of stall. Flaps counteract this by modifying the wing’s geometry.

When deployed, flaps:

- Increase the wing’s effective camber (curvature), promoting faster airflow over the top and higher suction.

- Delay airflow separation, allowing steeper angles of attack without stalling.

- In some cases, increase wing area (especially with slotted or Fowler flaps).

Plain and split flaps both enhance camber, but they do so through different mechanisms—one deflects the entire trailing edge downward, while the other splits the airfoil into two parts.

Plain Flaps: Simplicity with Limitations

A plain flap is a hinged section at the trailing edge of the wing that rotates downward as a single unit. It acts like an extension of the wing's lower surface, altering the overall curvature.

When deflected, the plain flap increases the wing’s angle of attack relative to the oncoming airflow. This change in camber boosts lift—but only up to a point. Because the upper surface contour changes abruptly at the hinge line, airflow tends to separate earlier than on a smooth airfoil, limiting maximum lift potential.

They are mechanically simple—just a hinge and actuator—making them reliable and lightweight. Many small general aviation aircraft, such as early Cessna models, use plain flaps due to their ease of maintenance and predictable behavior.

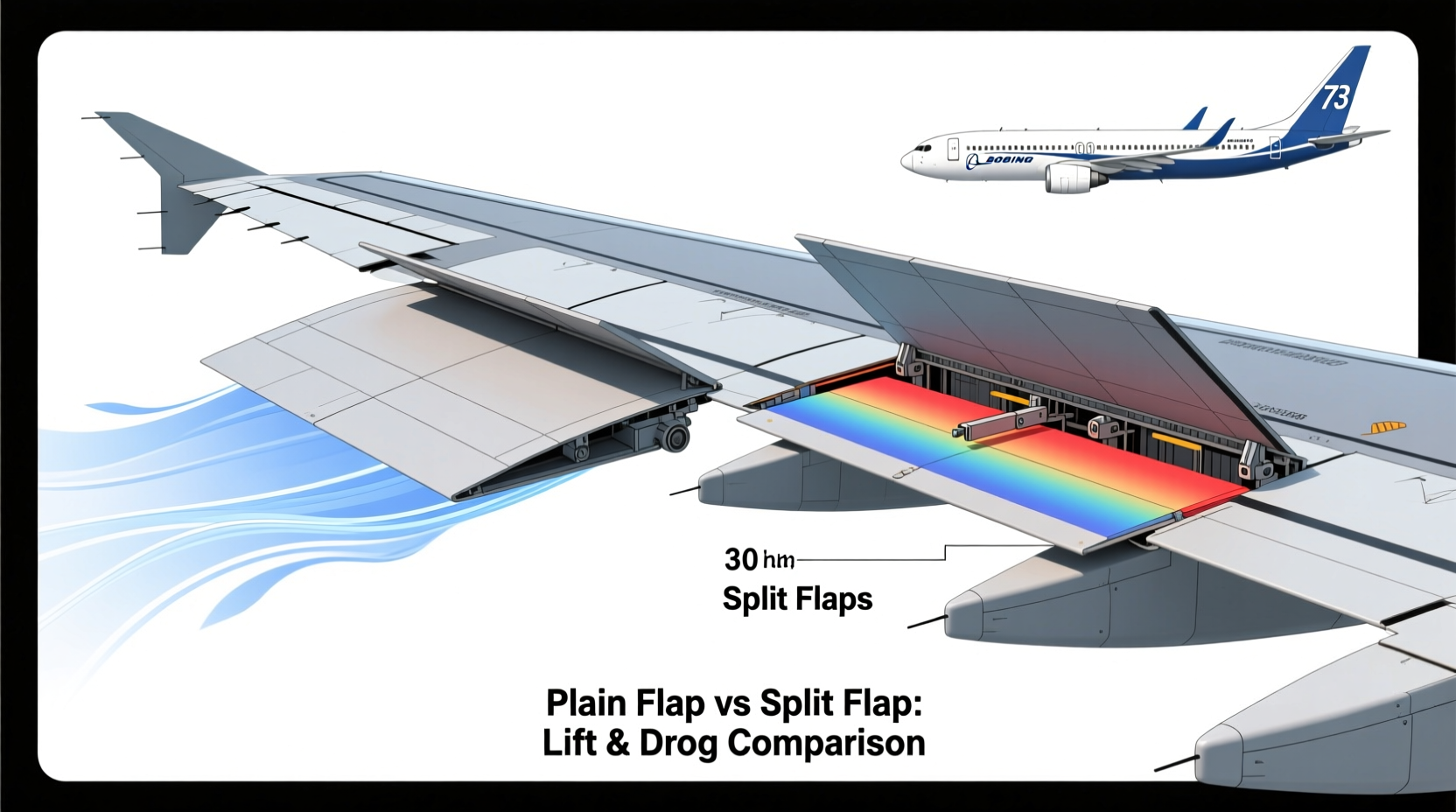

Split Flaps: Hidden Power in Asymmetry

Unlike plain flaps, split flaps consist of only the lower portion of the wing’s trailing edge detaching and angling downward, while the upper surface remains fixed. This creates a discontinuity in the airfoil, with air flowing over a smooth top surface and under a now-deflected lower segment.

The split flap’s design has a surprising advantage: it generates more lift than a plain flap at equivalent deflection angles. This occurs because the fixed upper surface maintains smoother airflow, delaying separation, while the lowered flap increases the effective camber and alters pressure distribution more dramatically.

Wind tunnel studies from the 1930s and 1940s—particularly those conducted by NACA (the predecessor to NASA)—showed that split flaps could produce up to 60% more lift than plain flaps at the same deflection. However, they also create significantly more drag, which can be beneficial during landing but detrimental during climb-out.

“Split flaps were a breakthrough in the 1930s because they delivered substantial lift gains without requiring complex mechanisms.” — Dr. Richard Whitcomb, Aerodynamics Pioneer, NASA

Comparative Analysis: Lift, Drag, and Practical Use

To understand which flap provides more lift, we must compare not just peak lift coefficients but also drag penalties, structural demands, and flight phase suitability.

| Feature | Plain Flap | Split Flap |

|---|---|---|

| Lift Increase (CL max) | Moderate (~50–70% increase) | High (~70–90% increase) |

| Drag Increase | Moderate | Significantly Higher |

| Flow Separation | Occurs earlier on upper surface | Better upper-surface attachment |

| Mechanical Complexity | Low (simple hinge) | Moderate (requires support arms) |

| Pitching Moment Change | Nose-down, predictable | Stronger nose-down tendency |

| Common Applications | Cessna 172, Piper Cherokee | Douglas DC-3, P-47 Thunderbolt |

The data shows that split flaps generally produce more lift than plain flaps due to superior control of airflow over the upper surface and a more aggressive alteration of pressure distribution. However, this comes at the cost of increased form drag and a more pronounced nose-down pitching moment, requiring stronger elevator authority.

Real-World Example: The Douglas DC-3 and Flap Performance

The Douglas DC-3, one of the most iconic aircraft of the 20th century, used split flaps extensively. Pilots praised its short-field performance, particularly on unpaved or short airstrips common in the 1930s and 1940s. With split flaps extended, the DC-3 could approach at speeds as low as 60 knots while maintaining stable control.

In contrast, contemporary aircraft using plain flaps required longer runways or higher approach speeds. The DC-3’s ability to operate from remote locations was directly tied to the effectiveness of its split flap system. Even today, vintage DC-3 operators note that full flap deployment dramatically reduces landing distance—not just because of added drag, but due to genuine lift enhancement.

This historical example underscores a key point: when maximum lift is the priority, split flaps have a proven edge.

Step-by-Step: How Pilots Evaluate Flap Effectiveness

Understanding flap performance isn’t just theoretical—it affects daily operations. Here’s how pilots assess which flap type benefits their aircraft:

- Review Aircraft Flight Manual (AFM): Check documented stall speeds with various flap settings to quantify lift improvements.

- Conduct Slow Flight Tests: Fly at constant altitude and reduce speed gradually with incremental flap deployment, noting control response and buffet onset.

- Compare Approach Angles: Observe glide slope stability with full flaps; steeper, controlled descents suggest higher lift-to-drag ratios.

- Analyze Landing Distance Data: Use performance charts to compare landing roll with and without flaps, isolating lift contribution from drag effects.

- Evaluate Pitch Behavior: Note trim changes upon flap extension; excessive nose-down moments may indicate strong lift generation behind the center of gravity.

This process helps pilots appreciate not just how much lift is gained, but how it integrates into overall aircraft behavior.

FAQ: Common Questions About Plain and Split Flaps

Do split flaps always provide more lift than plain flaps?

In most configurations, yes. Due to better preservation of upper-surface airflow and greater camber change, split flaps typically achieve higher maximum lift coefficients. However, the actual benefit depends on airfoil shape, flap chord, and deflection angle.

Why don’t modern aircraft use split flaps anymore?

While effective, split flaps create high drag and require robust support structures. Modern aircraft favor slotted or Fowler flaps, which offer even greater lift with better aerodynamic efficiency and smoother airflow management.

Can I retrofit split flaps onto an aircraft designed for plain flaps?

No—such modifications require extensive structural, aerodynamic, and certification work. The wing’s rear spar, skin, and control systems are designed around specific flap types. Unauthorized changes compromise safety and legality.

Expert Insight: Why Design Trade-Offs Matter

“The best flap isn’t the one that makes the most lift—it’s the one that balances lift, drag, weight, and controllability for the mission.” — Dr. Sandra Magnus, Former NASA Engineer and Aerospace Executive

This perspective is crucial. While split flaps win in raw lift production, plain flaps offer simplicity, lighter weight, and less adverse pitch behavior. For training aircraft where predictability matters more than ultimate performance, plain flaps remain a smart choice.

Conclusion: Which Flap Gives You More Lift?

The evidence is clear: split flaps generate more lift than plain flaps under comparable conditions. Their ability to maintain attached airflow over the upper wing surface while aggressively increasing camber gives them an aerodynamic edge. Historical use in high-performance piston-era aircraft confirms this advantage in practice.

However, “more lift” doesn’t always mean “better.” Increased drag, mechanical complexity, and stronger pitch-down tendencies make split flaps less suitable for many modern light aircraft. Plain flaps continue to serve well where reliability and simplicity outweigh peak performance.

Ultimately, the choice depends on the aircraft’s mission. For short-field bush planes or vintage warbirds, split flaps deliver tangible benefits. For trainers and personal cruisers, plain flaps strike the right balance.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?