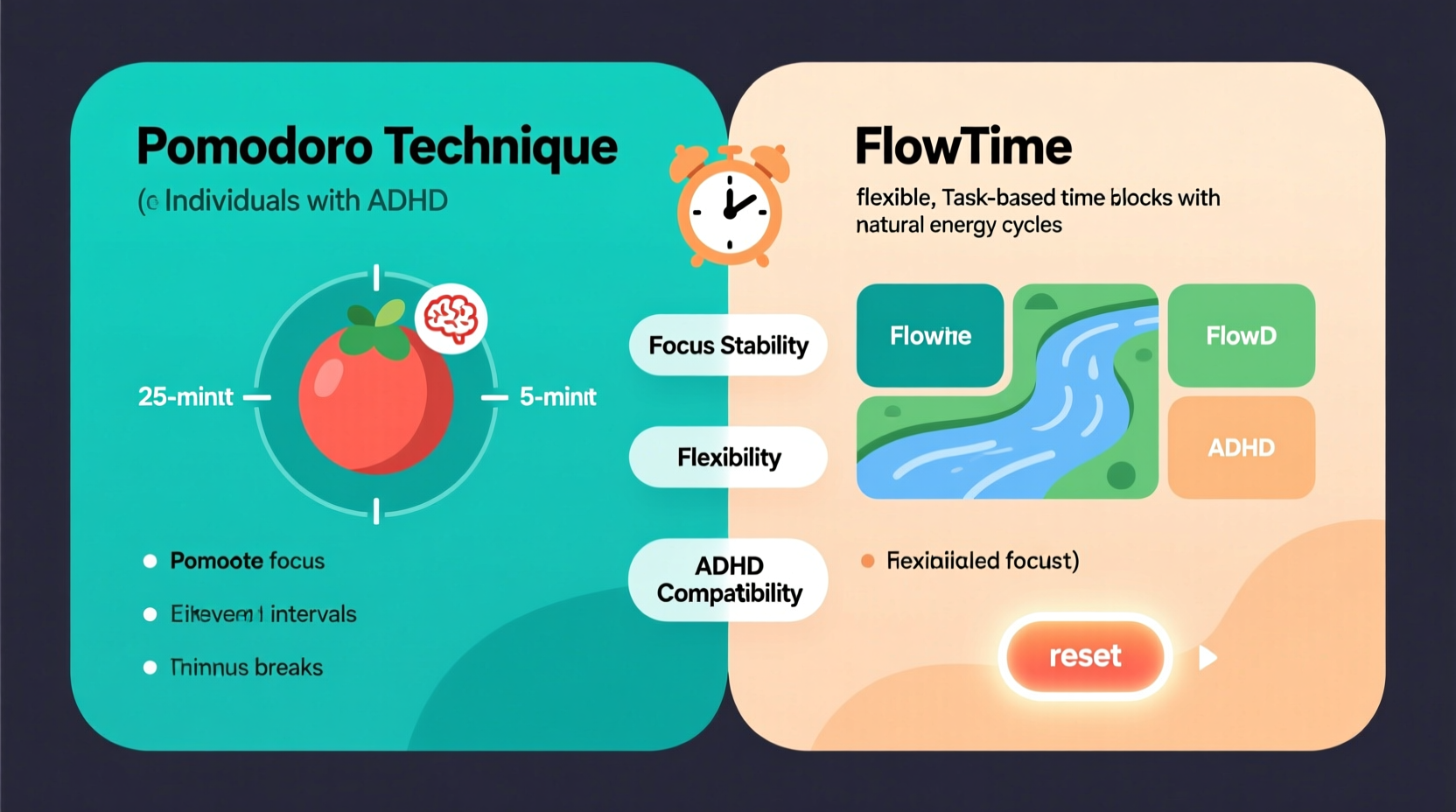

For individuals with ADHD, traditional time management systems often fall short. The struggle isn’t just about procrastination or lack of motivation—it’s rooted in how the brain regulates attention, executive function, and internal time perception. Two popular methods—Pomodoro Technique and Flowtime—offer alternative approaches to managing focus. But which one truly supports the unique cognitive rhythms of ADHD? This article compares both systems not as theoretical tools, but through the lens of real-world usability for neurodivergent minds.

Understanding the Core Challenges of ADHD and Time Management

ADHD is not a deficit of attention, but rather a dysregulation of it. People with ADHD don’t lack focus—they hyperfocus intensely when engaged, yet struggle to initiate or sustain effort on tasks that feel unstimulating. Traditional schedules and rigid timers can amplify stress rather than reduce it. The brain's dopamine system plays a critical role: low baseline levels make starting tasks difficult, and delayed rewards are less motivating.

This neurological profile makes structured time-blocking methods like Pomodoro appealing on paper—but potentially counterproductive in practice. Meanwhile, Flowtime, a more organic and intuitive approach, aligns with natural attention cycles. To evaluate their effectiveness, we must look beyond popularity and examine how each method accommodates unpredictability, emotional regulation, and task initiation—the three pillars of ADHD-friendly productivity.

The Pomodoro Technique: Structure with Drawbacks

Developed by Francesco Cirillo in the late 1980s, the Pomodoro Technique divides work into 25-minute intervals (called \"Pomodoros\") separated by 5-minute breaks. After four cycles, a longer break of 15–30 minutes is taken. The method relies on consistency, external timing, and task segmentation.

On the surface, this structure seems ideal for ADHD: small chunks lower the barrier to entry, and scheduled breaks prevent burnout. However, its rigidity becomes a liability. For someone with ADHD, a 25-minute timer can induce anxiety if they’re not “in the zone.” Interrupting deep focus at the sound of a bell disrupts momentum. Worse, failing to complete a full Pomodoro—common during distraction spikes—can trigger shame and abandonment of the entire system.

When Pomodoro Works for ADHD

- Task initiation: The “just start for 25 minutes” rule helps bypass resistance.

- Routine building: Predictable rhythm supports habit formation.

- External accountability: Timers act as an outside cue, compensating for weak internal regulation.

Yet even in these cases, adherence tends to drop after a few days. The problem lies in treating all tasks—and all brain states—the same way. A person with ADHD may finish a task in 18 minutes but must wait for the timer to end, wasting momentum. Or they may finally enter flow at minute 24, only to be interrupted.

Flowtime: A Flexible Alternative Rooted in Awareness

Created by programmer and productivity coach Christian Gruber, Flowtime replaces fixed intervals with awareness-based pacing. Instead of forcing work into boxes, you begin a task and check in periodically—every 30–60 minutes—to assess energy, progress, and next steps. Breaks happen when needed, not on a schedule.

The core principle: Work with your attention, not against it. Flowtime acknowledges that focus ebbs and flows. Some days require frequent pauses; others allow hours of uninterrupted output. Rather than measuring time spent, it emphasizes reflection and responsiveness.

“Productivity isn’t about filling time—it’s about respecting your mental state and working in alignment with it.” — Christian Gruber, creator of Flowtime

For ADHD, this flexibility is transformative. It removes the guilt of “failed” timers and honors hyperfocus when it occurs. There’s no penalty for working 40 minutes straight or taking a 20-minute walk mid-task. The emphasis shifts from compliance to self-awareness—a skill crucial for long-term ADHD management.

How Flowtime Supports ADHD Neurology

- No artificial urgency: Eliminates timer-induced anxiety.

- Honors hyperfocus: Allows deep work to continue without interruption.

- Encourages self-monitoring: Builds metacognition, a weak area in ADHD.

- Reduces task-switching penalties: Minimizes forced transitions that disrupt focus.

Unlike Pomodoro, Flowtime doesn’t assume equal capacity across days. It adapts to mood, sleep quality, medication timing, and environmental stimuli—all major variables in ADHD performance.

Direct Comparison: Pomodoro vs Flowtime for ADHD

| Factor | Pomodoro Technique | Flowtime |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Level | High – fixed intervals | Low – self-guided pacing |

| Flexibility | Low – interruptions are built-in | High – adapt to focus and energy |

| Initiation Support | Strong – “just one Pomodoro” lowers barriers | Moderate – requires self-direction |

| Hyperfocus Compatibility | Poor – forces breaks | Excellent – allows extended focus |

| Emotional Impact | Risk of frustration if timers fail | Lower pressure, promotes self-trust |

| Best For | Structured environments, routine tasks | Creative work, variable focus, ADHD |

The data suggests Flowtime is better aligned with ADHD cognitive patterns. However, this doesn’t mean Pomodoro has no place. Some individuals benefit from initial scaffolding before transitioning to a freer system. The key is progression—not permanence.

A Real-World Example: Sarah’s Shift from Pomodoro to Flowtime

Sarah, a freelance graphic designer diagnosed with ADHD at 28, used the Pomodoro Technique for six months. Initially, it helped her start client projects. But she noticed a pattern: she’d often hit creative flow around minute 20, only to be pulled out by the alarm. She’d either ignore the timer—undermining the system—or stop abruptly, losing ideas. On low-energy days, even starting one Pomodoro felt overwhelming.

After reading about Flowtime, she experimented. Instead of setting a timer, she began tracking when she started working and checked in every 45 minutes. She noted her focus level, progress, and whether she needed a break. Within a week, she completed two designs faster than usual. More importantly, she felt less guilty on slow days and more in control overall.

“Flowtime didn’t fix my ADHD,” she said, “but it stopped fighting against it. I’m not failing a system—I’m learning how I actually work.”

Step-by-Step Guide to Implementing Flowtime with ADHD

Transitioning to Flowtime requires a mindset shift—from enforcing discipline to cultivating awareness. Follow this sequence to build the habit gradually:

- Track Your Natural Rhythms (Day 1–3): For three days, simply log when you start and stop working on tasks. Note distractions, energy dips, and moments of deep focus. Use pen and paper or a notes app.

- Add Check-In Prompts (Day 4–7): Set a gentle reminder every 45–60 minutes to ask: “How focused am I? Do I need a break? What’s the next small step?” Answer briefly.

- Introduce Intentional Breaks: When a check-in reveals fatigue or distraction, take a 5–10 minute break. Move, hydrate, or step outside. Return only when ready.

- Reflect Daily: At day’s end, review your logs. Look for patterns: when do you focus best? What interrupts you? Adjust tomorrow’s plan accordingly.

- Iterate Based on Data: After a week, refine your approach. Maybe you check in every 30 minutes on chaotic days, or go 90 minutes when in flow. Let your brain guide the structure.

The goal isn’t perfect consistency, but increased self-knowledge. Over time, you’ll develop an internal sense of pacing that no timer can provide.

When to Combine Methods: A Hybrid Approach

Pure Flowtime isn’t always feasible—especially in jobs requiring punctuality or meetings. A hybrid model can offer balance. For example:

- Use Pomodoro for administrative tasks (emails, invoicing) where structure helps.

- Switch to Flowtime for creative or complex work requiring sustained attention.

- Apply micro-Pomodoros (10–15 minutes) on days when starting feels impossible.

This tiered strategy respects both external demands and internal limits. It also prevents all-or-nothing thinking: if one method fails, another can fill the gap.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can people with ADHD really benefit from any time management system?

Yes—but only if the system is adaptable. Rigid frameworks often backfire. The most effective methods are those that prioritize self-awareness over strict rules and allow for daily variation in energy and focus.

Does medication affect which method works better?

It can. On medicated days, some individuals find Pomodoro more manageable due to improved executive control. On unmedicated or off-cycle days, Flowtime’s flexibility may be essential. Track your response across different states to determine what fits each context.

Isn’t Flowtime just unstructured procrastination?

No. Flowtime isn’t a free-for-all—it’s a mindful, reflective process. Without regular check-ins and honest self-assessment, it can devolve into avoidance. The difference lies in intentionality: Flowtime requires active monitoring, not passive drifting.

Checklist: Choosing the Right Method for You

Use this checklist to determine which system—or combination—aligns with your current needs:

- ☐ I often lose track of time when working deeply → Favors Flowtime

- ☐ Starting tasks feels nearly impossible → Favors Pomodoro (or micro-timers)

- ☐ I get frustrated when interrupted by alarms → Favors Flowtime

- ☐ I work in a structured environment with deadlines → Consider hybrid approach

- ☐ I want to build self-awareness about my focus patterns → Favors Flowtime

- ☐ I respond well to external cues (alarms, apps) → Favors Pomodoro

Revisit this list weekly. Your optimal method may change with life circumstances, workload, or treatment adjustments.

Conclusion: Work With Your Brain, Not Against It

The debate between Pomodoro and Flowtime isn’t about which is objectively better—it’s about which aligns with your neurology. For many with ADHD, the answer leans strongly toward Flowtime. Its respect for natural attention cycles, absence of punitive timing, and emphasis on self-reflection make it a sustainable choice.

That said, there’s no universal fix. Experimentation is key. Start with small changes: shorten Pomodoro intervals, delay breaks during flow, or introduce check-ins without timers. The goal isn’t perfection, but progress toward a system that feels supportive, not stressful.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?