Navigating without a compass may seem like a lost art in the age of GPS and smartphones, but it remains an essential survival skill for hikers, campers, and outdoor enthusiasts. Whether you're caught off-trail, your phone dies, or you're simply embracing a minimalist adventure, knowing how to determine direction using only natural signs and simple tools can make all the difference. This guide explores proven, field-tested methods to orient yourself accurately—no electronics required.

Using the Sun’s Position

The sun is one of the most reliable directional indicators available. Its predictable path across the sky provides consistent reference points throughout the day. In the Northern Hemisphere, the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, arching toward the south at midday. The reverse is true in the Southern Hemisphere, where the sun arcs northward.

To estimate direction using the sun:

- Note the time of day. At sunrise, face the sun—you’re looking approximately east. South is to your right, north to your left, and west behind you.

- At noon (solar noon, not necessarily 12:00 on your watch), the sun is due south in the Northern Hemisphere and due north in the Southern Hemisphere.

- At sunset, facing the sun means you're looking west.

The Shadow Stick Method

This ancient technique uses shadows cast by the sun to pinpoint cardinal directions with surprising accuracy. It works best on flat, open ground with direct sunlight.

Step-by-step guide:

- Find a straight stick about 3 feet long and plant it vertically in level ground.

- Mark the tip of its shadow with a small stone or twig. This is your first reference point (Point A).

- Wait 15–30 minutes. The shadow will move as the sun progresses.

- Mark the new position of the shadow tip (Point B).

- Draw a straight line between Point A and Point B. This line runs approximately east-west, with Point A being west and Point B east.

- Stand with your left foot on Point A and right foot on Point B. You are now facing north (in the Northern Hemisphere).

This method works because shadows move from west to east during the day. The longer the interval between marks, the more accurate the reading—but even 15 minutes yields useful results.

Navigating by the Stars

At night, celestial navigation becomes your primary tool. The key is identifying reliable star patterns that indicate true north or south.

In the Northern Hemisphere, **Polaris**, the North Star, marks true north. To find it:

- Locate the Big Dipper (Ursa Major). The two stars forming the outer edge of its “bowl” point directly to Polaris.

- Polaris is the last star in the handle of the Little Dipper (Ursa Minor) and lies almost directly above the North Pole.

In the Southern Hemisphere, use the **Southern Cross** (Crux):

- Identify the four bright stars forming the cross.

- Extend the long axis of the cross about 4.5 times its length downward from the foot of the cross.

- The point where this line ends indicates the approximate location of the South Celestial Pole. Drop a vertical line to the horizon to find south.

“Celestial navigation isn’t just for sailors. Anyone who spends time under open skies should know how to read the stars.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Astrophysicist and Wilderness Educator

Using Natural Indicators in the Environment

Nature offers subtle clues that, when interpreted correctly, can support directional awareness. While not always 100% reliable, these signs become powerful when used in combination.

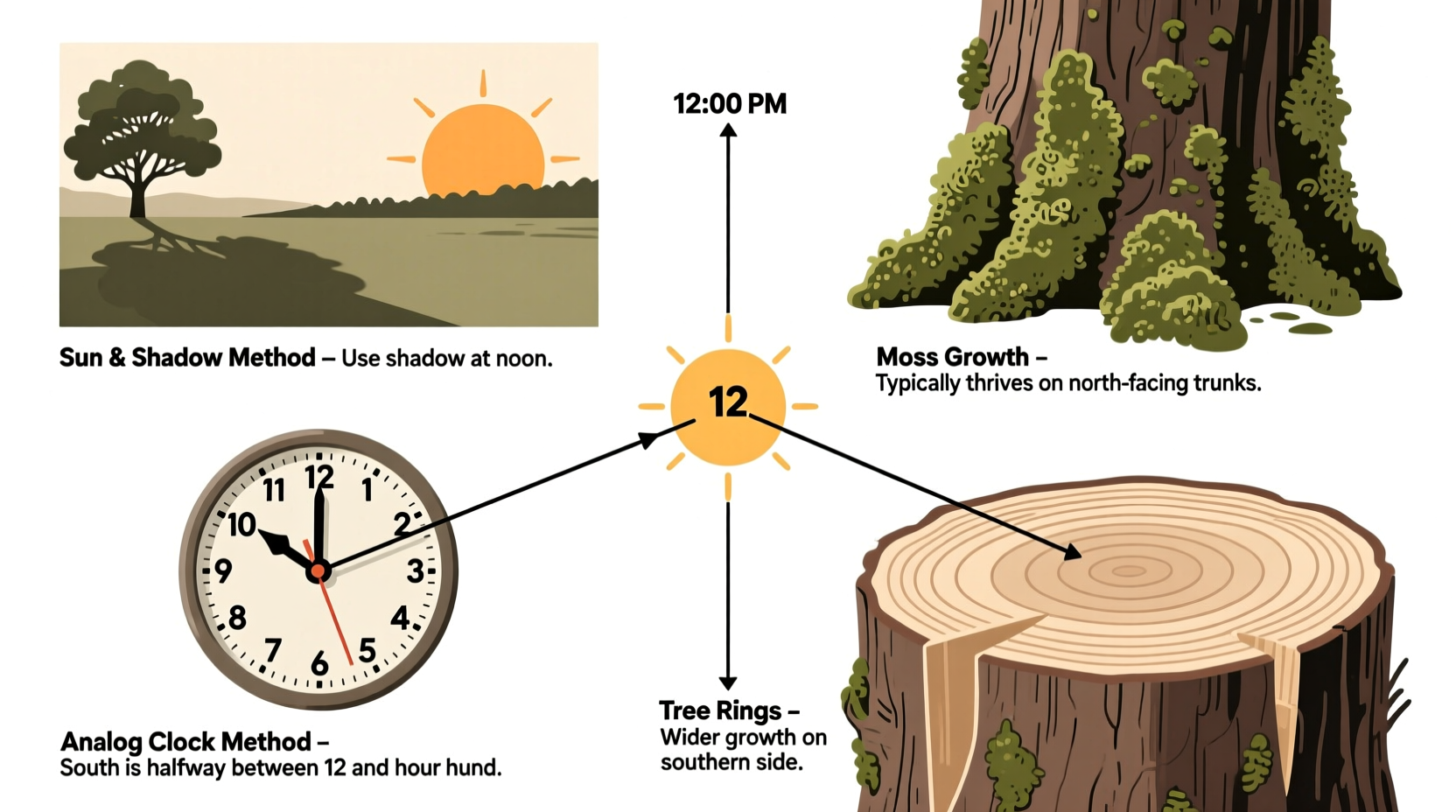

Tree growth patterns: In open areas, trees often grow denser foliage on their southern side (in the Northern Hemisphere) due to greater sun exposure. Moss tends to grow more abundantly on the northern side of tree trunks, where it's shadier and damper—but this isn’t universal. Always verify with other methods.

Ant hills: Some species of ants build mounds on the warmer, sun-facing side of trees or logs. In the Northern Hemisphere, these are often found on the south side.

Snow melt: On slopes, snow melts faster on south-facing sides due to increased sunlight. Observing which side of a hill or rock face clears first can provide directional hints.

| Natural Sign | Indicated Direction (N. Hemisphere) | Reliability |

|---|---|---|

| Moss on trees | North side | Moderate – varies by climate |

| Denser tree branches | South side | High in open areas |

| Ant mounds | South side | Moderate – species-dependent |

| Faster snowmelt | South-facing slopes | High in winter |

Using an Analog Watch as a Compass

If you have an analog watch and are in the Northern Hemisphere, you can turn it into a makeshift compass. This method works best when the watch shows standard time (not daylight saving adjusted) or when corrected accordingly.

How it works:

- Hold the watch flat and point the hour hand at the sun.

- Imagine a line bisecting the angle between the hour hand and the 12 o’clock mark.

- This bisecting line points south. North is opposite.

For example, if it’s 4:00 PM and you align the hour hand with the sun, the midpoint between 4 and 12 (roughly the 2 o’clock position) points south.

In the Southern Hemisphere, point the **12** on the watch at the sun. Then, bisect the angle between 12 and the hour hand—the midpoint points north.

Quick Checklist: Finding Direction Without a Compass

- ✅ Observe sunrise/sunset for rough east-west alignment

- ✅ Use the shadow stick method for precise daytime orientation

- ✅ Locate Polaris at night (Northern Hemisphere) or the Southern Cross (Southern Hemisphere)

- ✅ Check moss, tree growth, and snow patterns as supporting clues

- ✅ Use an analog watch to estimate south or north based on sun position

- ✅ Combine multiple methods to increase accuracy

A Real-World Scenario: Lost on a Hiking Trail

Consider this situation: Sarah, an experienced hiker, veered off-trail during a foggy morning trek in the Appalachian Mountains. Her phone had no signal, and her compass was missing from her pack. With daylight fading, she needed to reorient herself.

She waited until the sun briefly broke through the clouds around 10:30 AM. Using a trekking pole as a shadow stick, she marked the shadow tip, waited 20 minutes, then drew a line between the two points. She determined the east-west axis and deduced that north was perpendicular to it. By checking nearby trees for slightly denser foliage on one side, she confirmed her findings. Moving north, she eventually reached a known ridge trail and safely returned to camp.

Sarah’s success came from combining two independent methods—shadow tracking and environmental observation—to minimize error.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I use my smartphone if it’s out of battery?

No, a dead phone cannot run GPS or digital compass apps. However, if it has a physical orientation (like a built-in magnetometer), it might still help if powered externally—but this is unreliable. Always carry backup navigation methods.

Does the moss-on-trees rule always work?

No. While moss prefers shade and moisture (often found on north sides in the Northern Hemisphere), local conditions like wind, canopy cover, and microclimates can disrupt this pattern. Use it as a clue, not a definitive indicator.

What if I’m near the equator?

Near the equator, the sun passes nearly overhead, making shadow-based methods less effective at midday. Focus on sunrise and sunset positions, and use stellar navigation at night. Polaris is very low on the horizon, and the Southern Cross is visible seasonally.

Final Thoughts

Directional awareness is a quiet superpower—one that transforms uncertainty into confidence in the wild. While modern tools are invaluable, they are fragile. The ability to read the sun, stars, and landscape ensures you’re never truly lost. These skills don’t require special gear, only observation, patience, and practice.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?