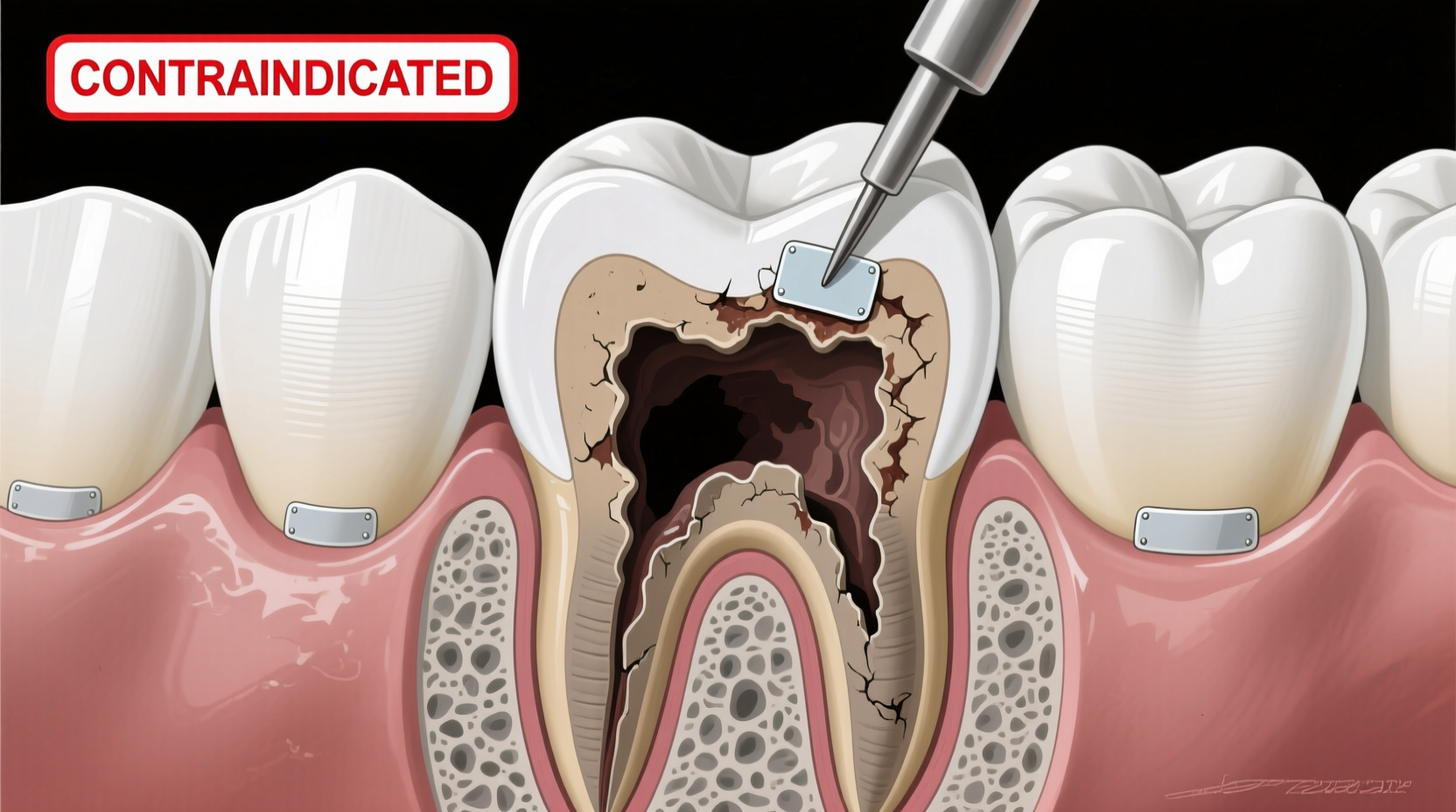

Dental sealants are a cornerstone of preventive dentistry, widely used to protect the occlusal surfaces of molars and premolars from carious lesions. Their ability to create a physical barrier over deep pits and fissures has made them a go-to intervention for reducing the incidence of coronal decay—especially in children and adolescents. However, their application is not universally appropriate. One critical limitation often misunderstood by both patients and practitioners is that sealants are contraindicated for proximal caries. Understanding why requires a close look at anatomy, caries progression, material science, and clinical outcomes.

Anatomy and Access: The Core Limitation

The proximal surfaces of teeth—the areas between adjacent teeth—are anatomically distinct from occlusal surfaces. These contact points lie below the height of contour and are inaccessible to direct visual inspection without radiographic support. Unlike the biting surfaces, which are exposed and easily isolated during sealant placement, proximal zones are narrow, tightly contoured, and surrounded by soft tissue and neighboring teeth.

Sealants require a dry, clean, and accessible surface to bond effectively. Moisture contamination from saliva or gingival crevicular fluid drastically reduces retention. In proximal areas, achieving adequate isolation is nearly impossible using standard cotton roll or dry-angle techniques. Even with rubber dam isolation, access to the actual site of interproximal decay is limited, making proper etching, bonding, and sealant placement impractical.

Caries Progression in Proximal Surfaces

Proximal caries typically begin just below the contact point, where plaque accumulates due to poor flossing or tight embrasures. These lesions progress inward, following the path of least resistance through enamel rods toward the dentinoenamel junction (DEJ). By the time a proximal lesion is detectable clinically or radiographically, it often extends beyond the confines of what a sealant can address.

Sealants work best on non-cavitated, early enamel lesions located on the outer third of enamel depth. Once caries reaches the middle or inner thirds—or involves the DEJ—it is no longer considered \"early stage\" and falls outside the scope of sealant therapy. At this point, remineralization via fluoride or infiltration with resin-based agents like Icon may be options, but traditional pit-and-fissure sealants offer little benefit.

“Placing a sealant over a proximal lesion is like locking the door after the thief has already entered. The damage is underway, and surface protection won’t stop subsurface progression.” — Dr. Linda Harper, Pediatric Dentist and Caries Management Specialist

Material Limitations and Clinical Outcomes

Resin-based sealants are designed to flow into microscopic fissures and polymerize under light activation. They lack the mechanical strength, adhesion, and marginal integrity needed to seal open or subgingival proximal defects. Even if applied, microleakage would occur rapidly, allowing continued bacterial infiltration and acid production beneath the sealant—a scenario worse than no treatment at all, as it masks ongoing decay.

Moreover, sealants do not release fluoride in sustained amounts (unlike glass ionomer cements), so they provide no therapeutic effect beyond physical blocking. This further limits their utility in active caries management. Studies show that sealed proximal lesions demonstrate higher failure rates and faster progression compared to properly restored ones.

Do’s and Don’ts: Sealant Application Guidelines

| Action | Recommended? | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Apply sealant on non-cavitated occlusal lesion | ✅ Yes | Effective prevention with high retention |

| Place sealant over visible proximal cavitation | ❌ No | Leads to undetected progression and failure |

| Use sealant after restoring a proximal cavity | ✅ Yes (adjacent surfaces) | Protects remaining vulnerable anatomy |

| Seal a tooth with radiographic proximal lesion | ❌ No | Lesion is already beyond sealant indication |

| Monitor arrested proximal lesion without intervention | ✅ Conditional | With excellent hygiene and fluoride, some stabilize |

Alternative Approaches to Managing Proximal Caries

When proximal caries is diagnosed, clinicians must shift from prevention to intervention. The choice of treatment depends on lesion depth, patient risk factors, and restorative goals.

- Non-Invasive: Remineralization Therapy – For very early, non-cavitated lesions confined to outer enamel, intensive fluoride regimens (high-concentration varnish, prescription toothpaste), chlorhexidine rinses, and dietary counseling can halt or reverse decay.

- Micro-Invasive: Resin Infiltration – Products like Icon (DMG America) use low-viscosity resin to penetrate demineralized enamel without drilling. Suitable for white-spot lesions extending less than halfway through enamel.

- Restorative: Composite or GIC Fillings – When caries reaches dentin or creates a cavitation, removal of infected tissue and placement of a bonded restoration is necessary. Proximal boxes often require matrix systems and careful contouring.

- Preventive Adjunct: Interproximal Sealants? – While true proximal sealants aren't feasible, some researchers have explored “extended” sealants that bridge into early proximal areas. These remain experimental and are not part of standard care.

Mini Case Study: A Misguided Attempt

A 12-year-old male presented with a small shadow on the distal of his lower left first molar, visible on bitewing X-ray. The dentist, aiming to avoid drilling, applied a sealant over the occlusal surface, hoping it might indirectly protect the adjacent area. Six months later, the lesion had progressed significantly into dentin, requiring a Class II composite restoration. The delay allowed irreversible damage. Post-treatment discussion revealed the initial approach was well-intentioned but misaligned with evidence-based guidelines. True proximal protection wasn’t achieved—and the false sense of security likely reduced the patient’s flossing compliance.

Step-by-Step: Proper Management of Early Proximal Lesions

Here’s a clinically sound protocol for handling suspected proximal decay:

- Diagnose Accurately: Use bitewing radiographs and clinical examination (explorer, transillumination) to assess lesion depth and activity.

- Assess Cavity Status: Determine if the lesion is cavitated. Any break in the enamel surface rules out sealant use.

- Evaluate Patient Risk: High-caries-risk patients may need more aggressive preventive strategies, including fluoride varnish every 3–6 months.

- Choose Intervention Level:

- Outer-third enamel: Remineralization + monitoring every 6 months.

- Middle-third enamel: Consider resin infiltration.

- Dentinal involvement: Restore promptly.

- Reinforce Home Care: Educate on proper flossing technique, interdental brushes, and fluoride exposure.

- Follow Up: Schedule recall based on risk—every 3 to 12 months—to track changes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can sealants prevent proximal caries indirectly?

Indirectly, yes—but only by reducing overall bacterial load. By preventing occlusal decay, sealants decrease the reservoir of cariogenic bacteria that could contribute to proximal disease. However, this does not equate to direct protection of interproximal surfaces.

Are there any products designed to seal proximal areas?

No commercially available product functions as a true “proximal sealant” in the way occlusal sealants do. Resin infiltration systems like Icon can stabilize early lesions but are not substitutes for traditional sealants and require specific case selection.

What should I do if my child has early signs of proximal decay?

Focus on prevention: improve brushing and flossing habits, use fluoride toothpaste twice daily, limit sugar intake, and visit your dentist regularly for professional fluoride applications and monitoring. Early action can often prevent the need for fillings.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Evidence Over Convenience

The temptation to use sealants as a universal shield against all types of caries is understandable—but misguided. While highly effective on occlusal surfaces, their application on proximal caries is contraindicated due to anatomical constraints, material limitations, and poor clinical outcomes. Recognizing this boundary is essential for ethical, evidence-based practice.

Instead of relying on inappropriate interventions, clinicians should embrace a stratified approach: accurate diagnosis, risk assessment, and timely use of remineralization, infiltration, or restoration as indicated. Patients benefit most when treatment aligns with the biology of the disease—not the convenience of the clinician.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?