Many home cooks treat shallots and onions as interchangeable, tossing one into a recipe in place of the other without considering the impact on flavor or texture. While both belong to the allium family and share visual similarities, they are distinct ingredients with unique chemical compositions, flavor profiles, and culinary roles. Mistaking one for the other can subtly—or dramatically—alter the outcome of a dish. Understanding the differences between shallots and onions is essential for precision cooking, whether you're building a delicate French sauce or roasting vegetables for a hearty stew. This guide breaks down their botanical origins, taste characteristics, structural properties, and optimal applications in both everyday and professional kitchens.

Definition & Overview

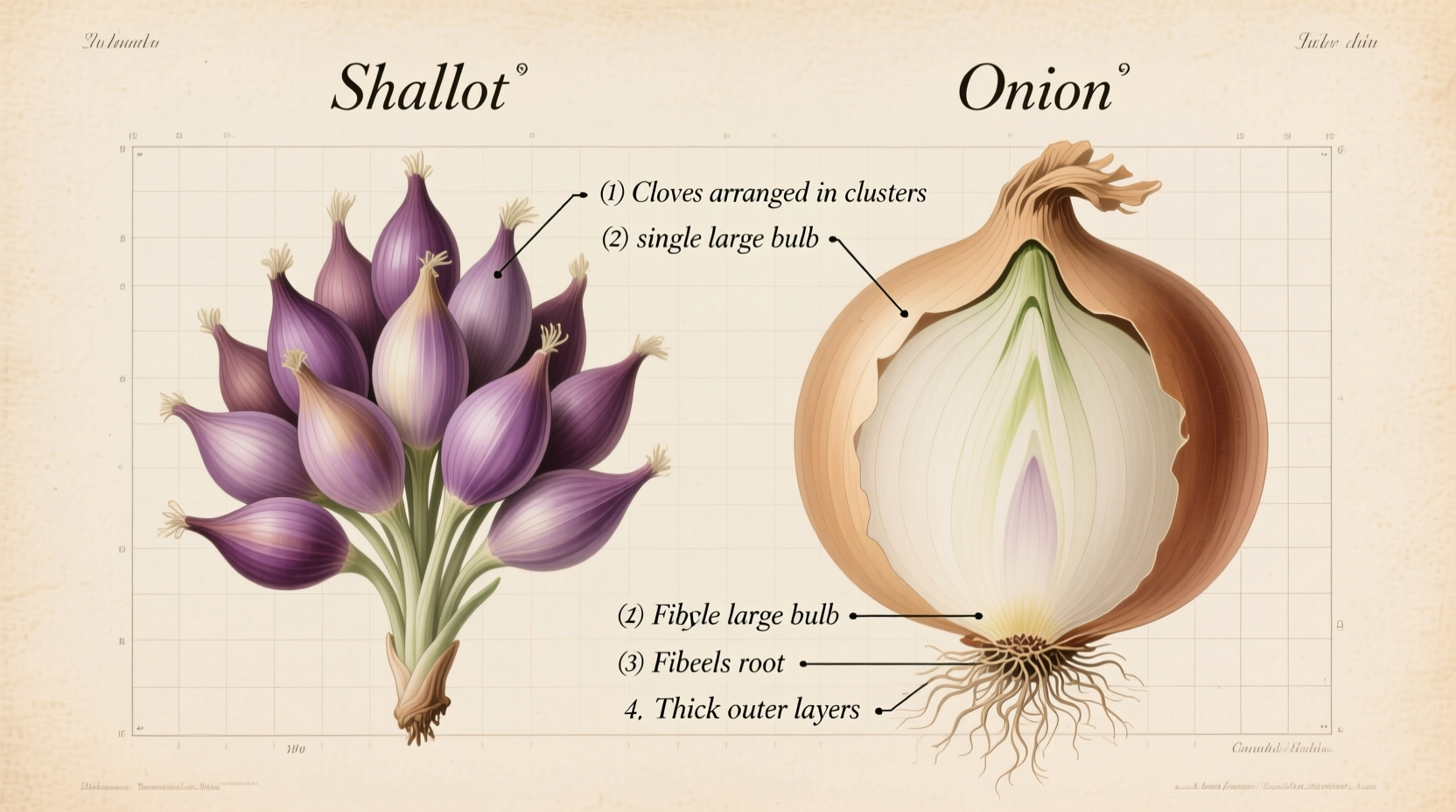

Shallots (Allium cepa var. aggregatum) are a type of bulbous vegetable in the Amaryllidaceae family, closely related to garlic and multiplier onions. Unlike common onions, shallots grow in clusters, resembling small garlic heads, with individual cloves encased in a thin, papery skin that ranges from coppery brown to rose-gold. They are prized in French, Southeast Asian, and Middle Eastern cuisines for their nuanced sweetness and lack of harsh pungency.

Onions (Allium cepa), by contrast, are single-bulb plants grown worldwide in numerous varieties, including yellow, white, red (purple), and sweet types like Vidalia or Walla Walla. Onions have a stronger, more assertive flavor profile due to higher sulfur compound concentrations, which contribute to their tear-inducing qualities and robust presence in cooked and raw preparations.

Both ingredients serve as aromatic foundations in global cuisines, but their divergent chemistry and structure make them suited to different culinary functions. Recognizing these distinctions allows cooks to elevate dishes with greater control over balance, depth, and finish.

Key Characteristics

| Characteristic | Shallot | Onion |

|---|---|---|

| Flavor Profile | Delicate, sweet, mildly garlicky; subtle earthiness with a hint of sharpness when raw | Bold, pungent, sulfurous; sharp bite when raw, caramelizes to deep sweetness |

| Aroma | Faintly floral, slightly nutty, less volatile | Strong, acrid, tear-inducing due to syn-propanethial-S-oxide |

| Texture | Finer-grained flesh; tender when cooked, holds shape well | Denser, coarser layers; softens significantly during prolonged cooking |

| Color & Form | Grows in clusters of cloves; coppery or golden-brown skin, pale grayish-purple flesh | Spherical single bulb; skin color varies (yellow, red, white); layered white or purple interior |

| Culinary Function | Refined base note; ideal for sauces, vinaigrettes, garnishes where subtlety matters | Structural backbone; used for bulk aromatics, soups, stews, grilling, frying |

| Shelf Life (Whole, Stored) | 1–2 months in cool, dry, dark place | Yellow/white: 2–3 months; Red: 1–2 months; Sweet onions: 2–4 weeks |

| Heat Level (Raw) | Low to moderate; rarely causes mouth burn | Moderate to high; can be biting or irritating raw |

Practical Usage: How to Use Each Ingredient

When to Use Shallots

Shallots excel in dishes requiring finesse. Their gentle heat and complex sweetness make them ideal for:

- Vinaigrettes and dressings: Minced raw shallot adds brightness without overpowering acidity. A classic French mustard vinaigrette often starts with 1 teaspoon finely chopped shallot per ¼ cup vinegar.

- Reduction sauces: In wine-based sauces like beurre blanc or demi-glace, shallots dissolve almost completely, contributing sweetness and body without fibrous residue.

- Raw applications: Thinly sliced shallots cure briefly in citrus juice or vinegar make elegant garnishes for seafood crudo, salads, or tacos.

- Stir-fries and quick sautés: Due to their smaller size and faster cook time, shallots integrate smoothly into fast-cooked dishes like Thai curries or scrambled eggs.

Pro Tip: Always mince shallots finely when using raw—they release flavor more evenly and avoid textural disruption. For reductions, sweat them gently in butter until translucent before adding liquid.

When to Use Onions

Onions provide volume, depth, and foundational savoriness. Choose onions when:

- Building mirepoix or sofrito: Yellow onions form the base of most Western stocks, soups, and braises. Combined with carrots and celery, they create a savory trinity that supports long-simmered dishes.

- Caramelizing: High sugar content makes yellow and sweet onions ideal for slow caramelization. Cooked low and slow over 30–60 minutes, they develop rich umami notes perfect for French onion soup or burger toppings.

- Grilling or roasting whole: Large bulbs hold up well to high heat. Halved onions grilled alongside meats add smoky sweetness.

- Adding crunch raw: Red onions, with their vibrant color and crisp bite, enhance salads, sandwiches, and salsas. Soak in cold water for 10 minutes to reduce sharpness if desired.

Cook’s Note: Never substitute raw white onion for shallot in a delicate salad dressing—the sulfur punch will dominate. If substituting cooked, adjust quantity: ½ cup diced onion ≈ ⅔ cup minced shallot, but expect a bolder result.

Variants & Types

Types of Shallots

Not all shallots are the same. Regional variations affect flavor and availability:

- Gray (French) Shallot: Considered the gold standard. Smaller, elongated cloves with grayish skin and pinkish flesh. Most aromatic and balanced; favored in haute cuisine.

- Echalion (Banana) Shallot: Larger, oval-shaped, with fewer cloves. Sweeter and milder, easier to peel and chop. Excellent for roasting or grilling.

- Jersey (Pink) Shallot: Grown in the UK and parts of the U.S. Milder than French, with a slightly more onion-like character. Good for pickling.

- Asian Shallot (Allium ascalonicum): Smaller, rounder, more pungent. Common in Chinese, Thai, and Indian cooking. Often fried into crispy garnishes (e.g., *bawang goreng*).

Types of Onions

Each onion variety serves a specific purpose:

- Yellow Onion: The workhorse. Pungent raw, transforms into deep sweetness when cooked. Best for soups, stews, sauces, and caramelizing.

- White Onion: Crisper and sharper than yellow, commonly used in Mexican cuisine for salsas and grilled dishes. Less sweet when cooked.

- Red (Purple) Onion: Mildly sweet with a peppery edge. Valued for color and crunch in salads, burgers, and pickles. Can turn blue-green in alkaline environments (e.g., baked beans).

- Sweet Onions (Vidalia, Walla Walla, Maui): Lower sulfur, higher water and sugar content. Best eaten raw or lightly grilled. Not ideal for long cooking—they can scorch easily.

| Ingredient | Type | Best Used For |

|---|---|---|

| Shallot | Gray/French | Sauces, vinaigrettes, fine dining applications |

| Echalion | Roasting, grilling, sautéing in bulk | |

| Jersery/Pink | Pickling, roasting, general use | |

| Asian | Frying, stir-fries, condiments | |

| Onion | Yellow | Mirepoix, stocks, caramelizing, general cooking |

| White | Salsas, tacos, Latin American dishes | |

| Red | Salads, sandwiches, pickling, garnishes | |

| Sweet (Vidalia, etc.) | Raw eating, grilling, onion rings |

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Confusion often arises between shallots, onions, and related alliums. Here's how they differ:

Shallot vs. Onion

- Structure: Shallots grow in clusters (like garlic); onions grow as single bulbs.

- Flavor Complexity: Shallots contain fructooligosaccharides that break down into sweeter compounds, giving them a more layered taste with hints of garlic and pear.

- Cooking Behavior: Shallots caramelize faster and more uniformly due to finer cell structure. Onions require longer cooking to achieve similar softness and sweetness.

- Nutrition: Per 100g, shallots have slightly more antioxidants (quercetin, kaempferol), vitamin C, and potassium than yellow onions.

Shallot vs. Scallion (Green Onion)

- Despite the name similarity, scallions (Allium fistulosum) are not immature shallots. They lack a developed bulb and are used primarily for their green tops and slender white shafts.

- Scallions offer mild onion flavor with grassy freshness—ideal for garnishing, stir-fries, and dumplings.

Shallot vs. Garlic

- While both grow in clusters, garlic (Allium sativum) has a much stronger, spicier profile due to allicin production upon cutting.

- Shallots lack the intense heat of raw garlic but share its tendency to multiply underground.

\"In classical French technique, we never replace shallots with onions in a velouté or emulsified sauce. The difference may seem slight, but it separates an amateur preparation from a professional one.\" — Chef Laurent Baudinet, Culinary Instructor, Institut Paul Bocuse

Practical Tips & FAQs

Can I substitute onions for shallots?

Yes, but with caveats. Use ½ the amount of finely minced yellow onion when replacing shallots in raw applications. For cooked dishes, increase cooking time slightly and consider finishing with a touch of garlic powder (¼ tsp per cup) to mimic shallot’s complexity. Avoid substitution in delicate sauces or vinaigrettes.

How do I store shallots and onions properly?

Store both in a cool, dry, dark, well-ventilated space—never in plastic bags or refrigerators unless cut. Ideal temperature: 45–55°F (7–13°C). Do not store near potatoes, which emit ethylene gas that accelerates sprouting. Once peeled, wrap tightly and refrigerate: shallots last 7–10 days; onions 7–14 days.

Why don’t my shallots caramelize evenly?

Shallots vary in moisture and sugar distribution. Slice uniformly (about ⅛ inch thick) and cook over medium-low heat in fat (butter or oil) for 15–20 minutes, stirring occasionally. Adding a pinch of salt draws out moisture and promotes even browning.

Are shallots healthier than onions?

Both are low-calorie, nutrient-dense vegetables rich in prebiotic fibers and flavonoids. Shallots rank higher in antioxidant activity according to ORAC (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity) values. However, the real health benefit lies in consistent consumption of alliums, linked to reduced inflammation and cardiovascular support.

What’s the best way to peel shallots?

Boil water and pour over trimmed shallots (ends removed) for 1 minute. Drain and rinse under cold water—skins slip off easily. Alternatively, microwave unpeeled shallots for 20 seconds to loosen skins.

Can I freeze shallots or onions?

Yes, but texture changes upon thawing. Freeze only if intended for cooked dishes. Peel, chop, and spread on a tray to freeze individually before transferring to airtight containers. Raw frozen shallots last 6 months; onions, 8 months. Blanching is unnecessary.

Storage Checklist:

- Keep whole bulbs dry and ventilated.

- Avoid refrigeration unless humidity is very high (>70%) or already cut.

- Check monthly for sprouting or soft spots.

- Never store in sealed containers—promotes mold.

- Use older stock first; rotate your supply.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Shallots and onions, while botanically related, play fundamentally different roles in the kitchen. Shallots bring elegance, subtlety, and complexity—ideal for refined sauces, dressings, and garnishes where balance is paramount. Onions deliver power, volume, and foundational savoriness, making them indispensable for soups, stews, roasts, and any dish needing robust aromatic depth.

The decision to use one over the other should be intentional, not arbitrary. Consider:

- The desired flavor intensity—delicate or bold?

- The cooking method—raw, quick sauté, or long simmer?

- The textural goal—fine integration or chunky presence?

- The cultural authenticity of the dish—does tradition favor one?

Mastering the distinction elevates cooking from formulaic to thoughtful. Next time a recipe calls for minced shallot, pause and ask: would onion truly suffice? More often than not, the answer reveals why precision in ingredient selection remains at the heart of great cuisine.

Challenge for the Reader: Prepare two versions of a basic red wine reduction—one with 1 minced shallot, the other with ¼ cup diced yellow onion. Taste side by side after reducing by half. Notice the difference in aroma, clarity, and finish. This simple experiment underscores the importance of choosing the right allium.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?