In the United States, few debates are as quietly passionate as the one over what to call a carbonated beverage. Is it “soda”? “Pop”? “Coke”? Or something else entirely? This isn’t just semantics—it’s a linguistic fingerprint of regional identity, shaped by migration patterns, industrial history, and cultural norms. While outsiders might dismiss the distinction as trivial, for many Americans, the word they use reveals where they grew up, where they feel at home, and sometimes even where they stand in a decades-long soft drink dialect war.

The Geographic Divide: Mapping America's Soft Drink Terminology

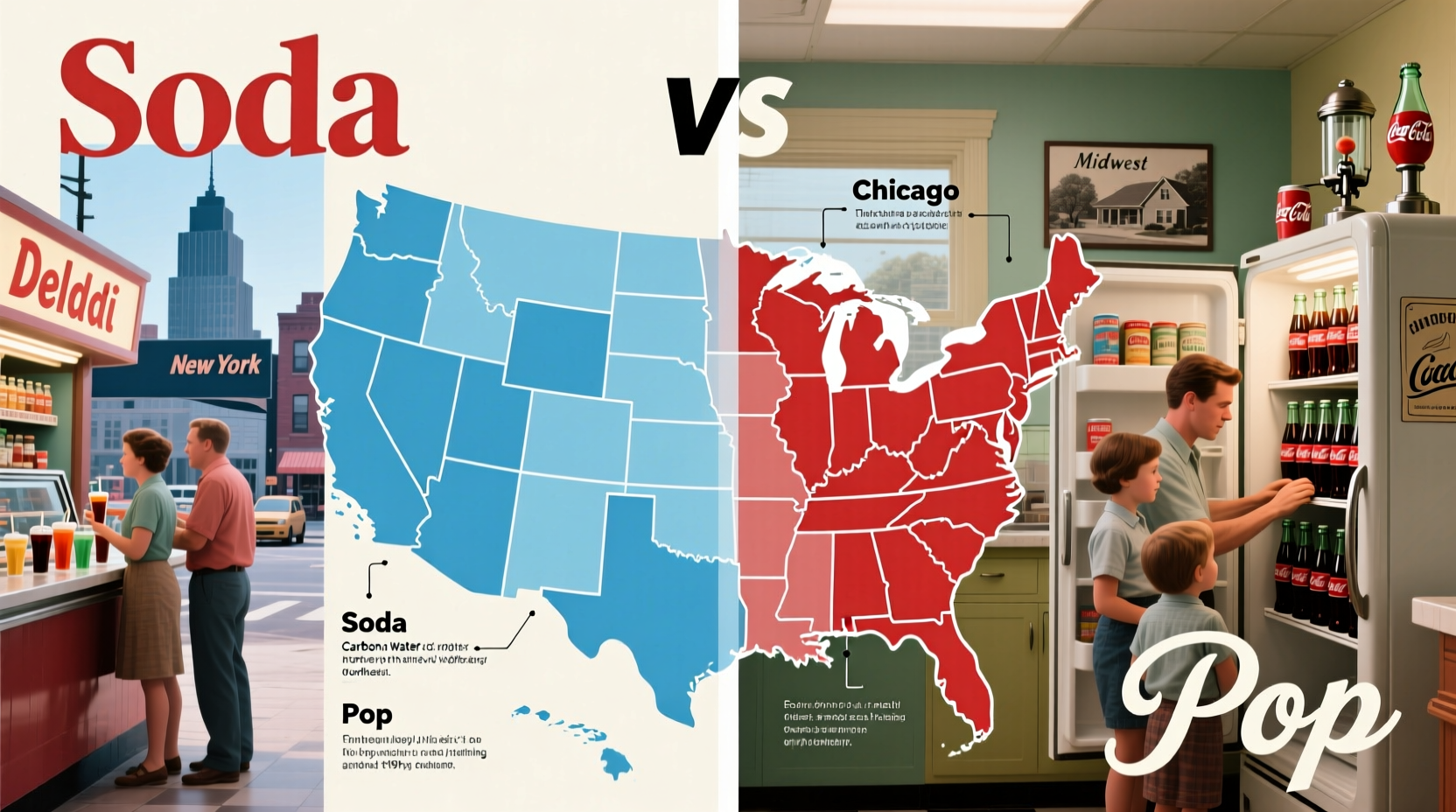

The most widely recognized split occurs between “soda” and “pop.” Broadly speaking:

- Soda dominates the Northeast, West Coast, and parts of Florida.

- Pop is favored in the Midwest, Pacific Northwest, and much of the northern Great Plains.

- Coke, used generically in the South, reflects brand dominance turning into a catch-all term—similar to “Kleenex” for tissues.

This distribution isn’t random. Historical settlement patterns played a role. For example, “pop” emerged in the late 19th century, likely onomatopoeic—imitating the sound of uncorking a bottle. It gained traction in areas with strong Scandinavian and German immigrant communities, particularly around the Great Lakes, where effervescent drinks were bottled locally and referred to as “pop” in advertisements.

Meanwhile, “soda” traces back to “soda water,” a term popularized by pharmacies and soda fountains in urban centers like New York and Boston. As these cities became media and cultural hubs, “soda” spread along coastal corridors.

Linguistic Roots and Cultural Influences

The choice between “soda” and “pop” isn’t just about geography—it’s also about language evolution and social identity. Sociolinguists have studied this phenomenon extensively, noting how regional speech patterns reinforce community bonds.

“The words we use for everyday items often carry invisible loyalty,” says Dr. Laura Montgomery, a sociolinguist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“Calling it ‘pop’ or ‘soda’ isn’t just about preference—it’s a subtle signal of belonging. People don’t usually switch terms, even after moving, because it feels like losing part of their identity.”

Brand influence has also skewed regional language. In the South, where Coca-Cola was invented and heavily marketed, “Coke” became synonymous with any soft drink. If someone in Atlanta asks, “Do you want a Coke?” they may very well be offering a Pepsi. This genericization of brand names—a process called “genericide”—is rare but powerful when it takes hold.

A Closer Look: Regional Breakdown and Usage Patterns

To understand the nuances, consider how different regions not only choose different terms but also resist others:

| Region | Preferred Term | Alternate Terms Used | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| New England, California | Soda | Soft drink | Rarely accept “pop”; “tonic” still used in parts of Massachusetts |

| Midwest (e.g., Ohio, Minnesota) | Pop | Soda (grudgingly) | Strong cultural attachment; “soda” sounds foreign to many |

| South (e.g., Georgia, Texas) | Coke | Soda, pop, soft drink | “Coke” used generically regardless of brand |

| Pacific Northwest | Pop | Soda | “Soda” gaining ground due to tech migration |

| Mid-Atlantic (e.g., Pennsylvania) | Mixed | Soda, pop | Urban areas lean “soda”; rural areas more likely to say “pop” |

The persistence of these terms highlights how deeply language is tied to place—even in the age of national advertising and digital communication.

Mini Case Study: The Michigan Family in Atlanta

The Petersons moved from Grand Rapids, Michigan, to Atlanta, Georgia, in 2018. At their first neighborhood barbecue, 12-year-old Emma asked, “Can I get a pop?” The host handed her a Coca-Cola, assuming that’s what she wanted. When she clarified she meant Sprite, the host chuckled: “Oh, you mean a soda!” Emma corrected him: “No, a pop.” The confusion sparked a lighthearted conversation, but over time, Emma noticed she started saying “Coke” when asking for any soft drink—just to avoid misunderstandings. Her parents, however, still insist on “pop,” even if it earns them puzzled looks.

This small shift illustrates how language adapts under social pressure. While younger generations may blend terms, older adults often maintain their original dialect as a point of pride.

Why the Debate Matters Beyond Vocabulary

On the surface, “soda vs pop” seems trivial. But linguists see it as a window into broader cultural dynamics. These micro-dialects reflect isolation, innovation, and resistance to homogenization. They also reveal how commerce shapes speech. For instance, bottling companies historically aligned with regional preferences—Pepsi, headquartered in North Carolina, reinforced “Coke” culture in the South, while independent bottlers in the Midwest promoted “pop” as a neutral, inclusive term.

Moreover, the debate has entered pop culture. TV shows like *Fargo* (set in Minnesota) use “pop” consistently, grounding characters in authenticity. Meanwhile, East Coast sitcoms default to “soda,” rarely acknowledging alternatives. This lack of representation can make speakers of minority terms feel linguistically marginalized.

Step-by-Step Guide: Navigating the Soft Drink Naming Landscape

Whether you’re relocating, traveling, or crafting region-specific marketing, here’s how to adapt:

- Listen First: Pay attention to what locals say in casual conversation.

- Match the Majority: In the South, use “Coke” unless specifying brand; in the Midwest, “pop” is safest.

- Avoid Correcting: If someone calls a Mountain Dew a “soda,” don’t argue—accept the variation.

- Use Neutral Terms When Unsure: “Soft drink” or “fizzy drink” avoids regional bias.

- Respect Identity: Don’t mock someone’s choice of term—it’s tied to upbringing and pride.

Checklist: Are You Using the Right Term for the Region?

- ✅ In New York or L.A.? Use “soda.”

- ✅ In Chicago or Minneapolis? Say “pop.”

- ✅ In Dallas or Nashville? “Coke” is acceptable as a general term.

- ✅ In Philadelphia? Be prepared for mixed usage—ask for clarification.

- ✅ Speaking nationally? Opt for “soft drink” to stay neutral.

- ✅ Writing dialogue? Match character background to terminology for authenticity.

FAQ

Is “tonic” still used anywhere?

Yes, primarily in eastern Massachusetts, especially among older generations. “Tonic” (short for “tonic water”) was once common in pharmacy-based soda fountains and has persisted in localized usage.

Why do some people say “coke” for all soft drinks?

This stems from Coca-Cola’s early dominance in the Southern U.S. As the most widely available brand, “Coke” became a generic term through habitual use, much like “Xerox” for photocopying.

Has social media changed soft drink terminology?

Yes, gradually. Younger generations exposed to diverse dialects online are more likely to understand multiple terms, though personal usage often remains rooted in regional upbringing.

Conclusion

The “soda vs pop” debate is more than a quirky linguistic divide—it’s a living record of American migration, industry, and identity. From the soda fountains of Boston to the pop bottles of Fargo, each term carries history in its syllables. Understanding these differences fosters better communication, cultural sensitivity, and even marketing effectiveness. Whether you sip a Coke, pop, or soda, recognizing the story behind the name adds depth to every fizz.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?