Spinach has long been celebrated as a nutritional powerhouse, particularly for its iron content. Thanks in large part to the iconic cartoon character Popeye, who gained superhuman strength from a can of spinach, this leafy green has become synonymous with vitality and health. But beyond the mythos, what does science say about spinach as a source of iron? While it is indeed rich in iron by volume, the reality of its bioavailability—how well the body absorbs and uses that iron—is more complex than popular belief suggests. Understanding the true role of spinach in meeting dietary iron needs requires a closer look at nutrient composition, absorption inhibitors, preparation methods, and its place within a balanced diet.

For home cooks, nutrition-conscious eaters, and culinary educators, knowing how to maximize the benefits of spinach while navigating its limitations is essential. This article provides a comprehensive, evidence-based examination of spinach’s iron content, its nutritional context, and practical strategies for incorporating it effectively into meals to support iron intake without relying on outdated assumptions.

Definition & Overview

Spinach (Spinacia oleracea) is an edible flowering plant in the Amaranthaceae family, cultivated primarily for its dark green, tender leaves. Native to central and western Asia, spinach was introduced to Europe in the 12th century and has since become a staple in cuisines worldwide—from Indian saag dishes to Mediterranean spanakopita and American salads.

Culinarily, spinach is classified as a leafy green vegetable with a mild, slightly earthy flavor that becomes sweeter when cooked. It is available in multiple forms: raw (baby or mature leaves), frozen, canned, and dried. Its versatility allows it to be used in raw applications like salads and smoothies, as well as cooked preparations such as sautés, soups, casseroles, and fillings.

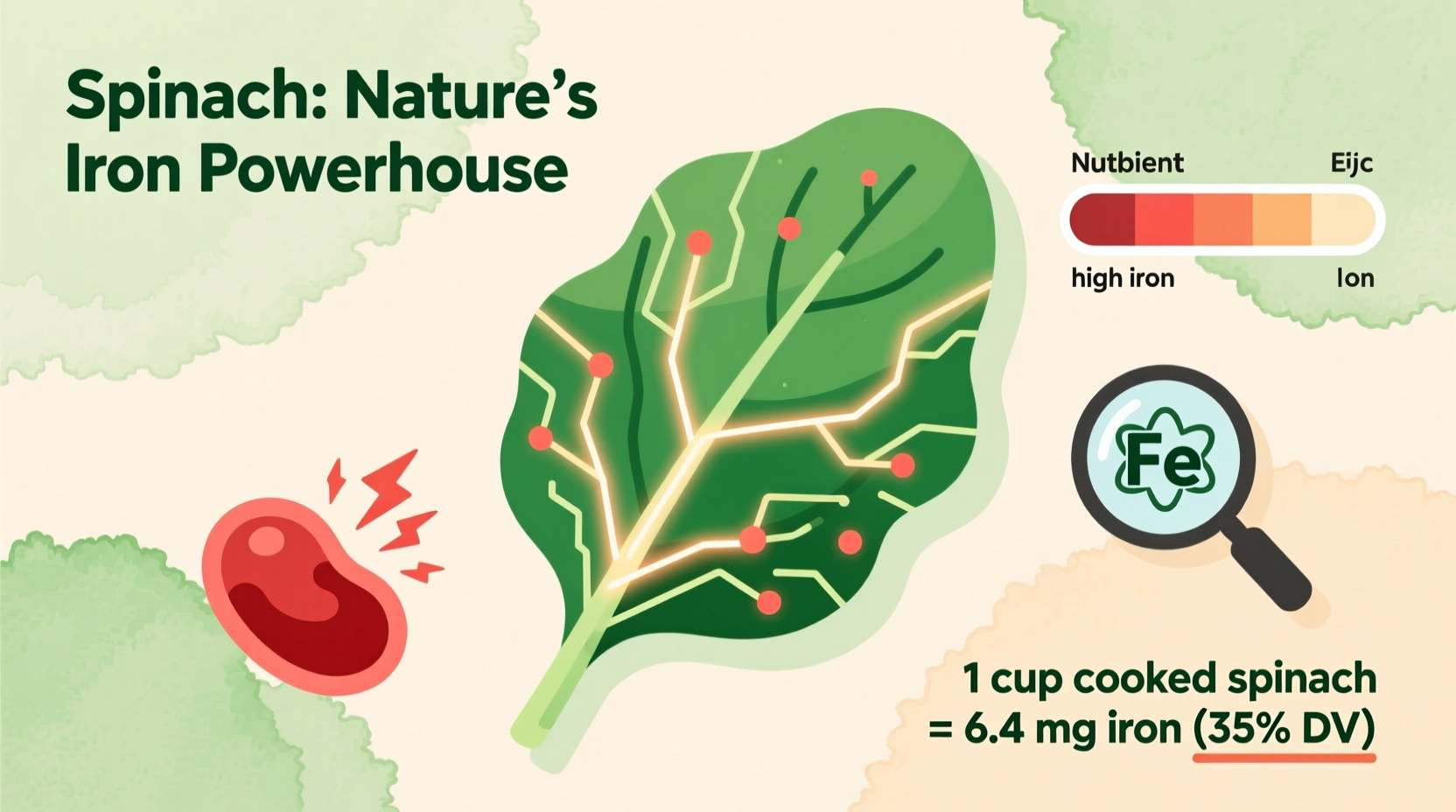

Nutritionally, spinach is low in calories but dense in vitamins and minerals. It is especially rich in vitamin K, vitamin A (as beta-carotene), folate, magnesium, and antioxidants like lutein and zeaxanthin. Of particular interest is its iron content, which ranks among the highest of all vegetables—yet its effectiveness in preventing or treating iron deficiency depends heavily on how it's consumed.

Key Characteristics

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Flavor Profile | Mildly earthy, slightly grassy when raw; mellows and sweetens with cooking. |

| Aroma | Fresh, green, vegetal—especially pronounced in young leaves. |

| Color & Form | Deep green leaves; flat-leaf, savoy (crinkled), or semi-savoy varieties. |

| Iron Content (per 100g raw) | Approximately 2.7 mg of non-heme iron. |

| Culinary Function | Bulk addition to dishes, nutrient booster, color enhancer, base for sauces and dips. |

| Shelf Life | 3–7 days refrigerated (raw); up to 12 months frozen. |

| Digestibility | Raw spinach contains oxalates that may inhibit mineral absorption; cooking improves digestibility. |

Practical Usage: How to Use Spinach for Maximum Iron Benefit

The key to leveraging spinach as a meaningful source of iron lies not just in eating it, but in how it is prepared and paired. Iron from plant sources—known as non-heme iron—is less efficiently absorbed than heme iron found in animal products. However, absorption can be significantly enhanced through strategic food combinations and cooking techniques.

Increase Iron Absorption with Vitamin C

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is one of the most effective enhancers of non-heme iron absorption. When consumed in the same meal, vitamin C can increase iron uptake from spinach by up to sixfold. Practical pairings include:

- Sautéed spinach with lemon juice and cherry tomatoes

- Spinach salad with orange segments, bell peppers, and strawberries

- Smoothie with spinach, pineapple, mango, and a squeeze of lime

A simple rule: aim for at least 50–100 mg of vitamin C per meal containing spinach—equivalent to half a medium orange or one small red bell pepper.

Cooking Methods That Improve Bioavailability

While raw spinach retains more vitamin C, cooking reduces oxalic acid—a compound that binds to iron and calcium, inhibiting their absorption. Steaming or lightly boiling spinach can reduce oxalate levels by 30–87%, depending on duration and method.

Recommended technique: Steam spinach for 3–5 minutes until wilted, then immediately plunge into cold water to preserve color and nutrients. This method maintains a balance between preserving vitamin C and reducing oxalates.

TIP: Do not discard the cooking water when boiling spinach if you're using it in soups or sauces—the leached minerals, including some iron, remain in the liquid.

Pairing Avoidances: What Not to Combine with Spinach

To optimize iron absorption, avoid consuming spinach alongside substances that inhibit non-heme iron uptake:

- Calcium-rich foods: Milk, cheese, yogurt, and fortified plant milks can interfere with iron absorption when eaten simultaneously.

- Tannins: Found in tea, coffee, and red wine—wait at least one hour after a spinach-rich meal before consuming these beverages.

- Phytates: Present in whole grains and legumes—soaking, fermenting, or sprouting these foods can reduce their inhibitory effect.

Professional Culinary Applications

In restaurant kitchens, chefs use spinach not only for flavor and color but also as a functional ingredient. Puréed cooked spinach is incorporated into pasta dough (e.g., ravioli), sauces, and grain pilafs to boost nutrition discreetly. In fine dining, blanched and finely chopped spinach appears in quenelles, mousses, and emulsions where texture and vibrancy are critical.

One innovative technique involves flash-freezing spinach purée in ice cube trays—chefs can then drop a nutrient-dense cube directly into risottos, soups, or scrambled eggs without altering consistency.

Variants & Types of Spinach

Not all spinach is created equal. Different varieties offer distinct textures, flavors, and suitability for specific cooking methods. Choosing the right type enhances both culinary results and nutrient retention.

- Baby Spinach: Harvested early, with tender leaves and mild flavor. Ideal for raw salads, sandwiches, and quick sautés. Slightly lower in oxalates than mature spinach.

- Savoy Spinach: Crinkled, dark green leaves with robust texture. Best suited for cooking due to its hearty structure. Commonly found in supermarkets and farmers' markets.

- Flat-Leaf (Semi-Savoy) Spinach: Smooth leaves that are easier to clean. Often used in commercial processing and freezing. Performs well in blended applications like smoothies and soups.

- Frozen Spinach: Typically blanched before freezing, which reduces oxalates and preserves iron content. More concentrated by volume (due to wilting during processing), making it excellent for cooked dishes.

- Canned Spinach: Less common today due to texture degradation, but still used in institutional cooking. Higher sodium content unless labeled \"low-sodium.\"

| Type | Best For | Iron Retention After Cooking | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baby Spinach | Raw consumption, light cooking | Moderate (higher vitamin C retained) | Lower fiber, gentler on digestion |

| Savoy Spinach | Sautes, stews, gratins | High (dense leaf structure) | Requires thorough washing |

| Frozen Spinach | Casseroles, dips, baked dishes | Very high (pre-cooked, concentrated) | Drain excess water before use |

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Spinach is often compared to other dark leafy greens in terms of iron content and nutritional value. While all are beneficial, significant differences exist in iron concentration and bioavailability.

| Green | Iron (mg per 100g raw) | Oxalate Level | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spinach | 2.7 | High | Widely available, versatile |

| Swiss Chard | 1.8 | High | Vibrant stems, good in stir-fries |

| Kale | 1.5 | Low to moderate | Higher vitamin C, better iron absorption |

| Collard Greens | 0.7 | Moderate | Traditional in Southern cuisine |

| Mustard Greens | 1.1 | Low | Pungent flavor, excellent sautéed |

“When evaluating greens for iron, consider not just quantity but quality of absorption. Mustard greens may have less iron than spinach, but their lower oxalate content means more of that iron actually reaches the bloodstream.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Registered Dietitian and Plant Nutrition Specialist

Practical Tips & FAQs

Q: Is spinach really high in iron?

A: Yes, raw spinach contains about 2.7 mg of iron per 100 grams, which is relatively high for a vegetable. However, due to the presence of oxalic acid, only about 1.5–2% of that iron is absorbed by the body when eaten raw. Cooking improves bioavailability slightly, but pairing with vitamin C remains crucial.

Q: Can spinach replace meat as an iron source?

A: Not entirely. While spinach contributes to daily iron intake, it should not be relied upon as the sole source, especially for individuals with increased needs (e.g., pregnant women, adolescents, those with anemia). A combination of heme iron (from meat, poultry, fish) and enhanced non-heme sources (like properly prepared spinach) is optimal.

Q: How much spinach should I eat daily for iron?

A: There is no official recommendation specific to spinach. However, including 1–2 cups of cooked spinach 2–3 times per week, paired with vitamin C-rich foods, can meaningfully contribute to iron intake. The RDA for iron is 8 mg/day for men and postmenopausal women, 18 mg/day for premenopausal women.

Q: Does blending spinach destroy nutrients?

A: No—blending preserves most nutrients, including iron. In fact, breaking down cell walls through blending may enhance the release of certain minerals. To maximize benefit, add citrus fruits, kiwi, or tomatoes to your smoothie.

Q: Can too much spinach be harmful?

A: For most people, moderate consumption is safe. However, individuals prone to kidney stones (especially calcium-oxalate type) should limit intake due to spinach’s high oxalate content. Those on blood thinners should maintain consistent vitamin K intake, as spinach is extremely rich in this nutrient.

Iron-Boosting Spinach Checklist

- ✔ Choose frozen or lightly cooked spinach over raw for better iron availability

- ✔ Add lemon juice, tomatoes, or bell peppers to every spinach dish

- ✔ Avoid serving spinach with dairy or tea/coffee at the same meal

- ✔ Combine with legumes (lentils, chickpeas) for synergistic plant-based iron

- ✔ Store fresh spinach in a sealed container with a paper towel to absorb moisture

Summary & Key Takeaways

Spinach is a valuable contributor to dietary iron, but its reputation as a standalone solution for iron deficiency is overstated. With approximately 2.7 mg of iron per 100 grams, it ranks among the top plant-based sources—but its high oxalate content limits absorption unless carefully managed.

The real power of spinach lies in how it is used. When cooked gently and paired with vitamin C-rich ingredients, its iron becomes significantly more bioavailable. Strategic avoidance of inhibitors like calcium and tannins further enhances its nutritional impact. Among leafy greens, spinach offers unmatched versatility and nutrient density, though alternatives like kale and mustard greens may offer better absorption profiles.

For home cooks and health-conscious eaters, the takeaway is clear: embrace spinach not as a miracle food, but as a smart, science-backed component of a diverse, balanced diet. By applying simple culinary principles—pairing, timing, and preparation—you can transform this humble green into a genuine ally in maintaining healthy iron status.

Use spinach wisely—not just because Popeye did, but because modern nutrition tells us how.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?