The term “tomato bug” commonly refers to several insect species that feed on tomato plants, but most frequently denotes the red-shouldered stink bug (Thyanta custator) or related pentatomid pests such as the green stink bug (Acrosternum hilare). These insects are significant agricultural nuisances, capable of causing substantial damage to solanaceous crops through direct feeding and pathogen transmission. Understanding their developmental biology is essential for effective pest monitoring, organic control strategies, and integrated pest management (IPM) in both backyard gardens and commercial farming operations. The complete life cycle of a tomato bug consists of three primary stages: egg, nymph, and adult—each with distinct morphological, behavioral, and ecological characteristics.

For home gardeners and small-scale producers, recognizing these stages allows timely intervention before irreversible plant damage occurs. For culinary professionals sourcing locally grown produce, awareness of pest cycles supports informed decisions about seasonal availability and quality. This article provides a comprehensive breakdown of the tomato bug’s ontogenetic progression, emphasizing visual identification, environmental triggers, and practical mitigation approaches grounded in entomological science.

Definition & Overview

Tomato bugs are phytophagous (plant-feeding) hemipterans belonging to the family Pentatomidae, commonly known as stink bugs due to their ability to emit foul-smelling defensive chemicals when disturbed. While not all stink bugs target tomatoes, certain species exhibit strong host specificity toward Solanum lycopersicum, making them particularly problematic during fruiting seasons.

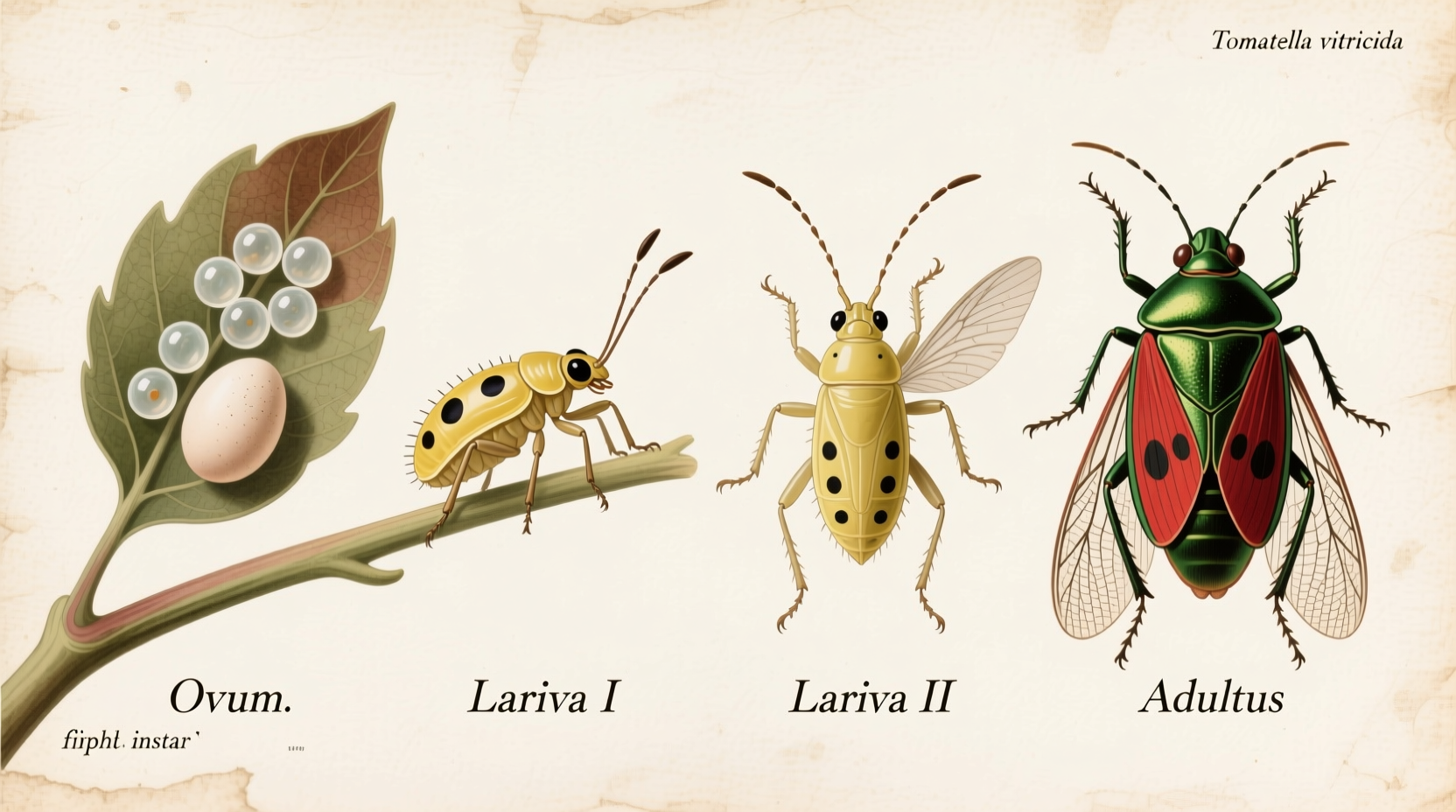

The development of a tomato bug follows an incomplete metamorphosis (hemimetabolous development), meaning it progresses through egg, multiple nymphal instars, and finally matures into a winged adult—without a pupal stage. Unlike holometabolous insects such as butterflies or beetles, nymphs resemble miniature versions of adults but lack fully developed reproductive organs and wings. This gradual transformation enables continuous feeding throughout development, increasing cumulative damage to host plants.

Development duration varies depending on temperature, humidity, food availability, and species. Under optimal conditions (75–85°F / 24–29°C), the entire lifecycle from egg to adult typically spans 5 to 8 weeks. Multiple generations may occur annually in warm climates, especially in USDA zones 7 and above, leading to overlapping populations that complicate control efforts.

Key Characteristics Across Life Stages

Each developmental phase presents unique identifying features critical for accurate scouting and targeted response:

| Stage | Size | Color/Appearance | Mobility | Feeding Behavior | Lifespan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egg | ~1 mm diameter | Barrel-shaped, pale white to yellowish; laid in clusters of 10–14 | Immobile | Non-feeding (embryonic) | 4–7 days |

| Nymph (Instar 1–2) | 2–4 mm | Bright red-orange abdomen with black thorax; resembles ladybugs | Low mobility, stays near egg mass | Begin piercing stems and soft fruit tissue | 5–7 days per instar |

| Nymph (Instar 3–5) | 5–10 mm | Darkening body, developing wing pads; greenish-gray with reddish accents | Moderate movement between leaves and fruits | Increased sap extraction from leaves, flowers, and immature fruit | 6–10 days per instar |

| Adult | 12–15 mm long | Oval, shield-shaped body; green or brown with red or orange markings on shoulders | Highly mobile, capable of flight | Deep punctures into mature fruit, causing catfacing, necrosis, and secondary rot | Several months (overwinters in some regions) |

These physical transitions correlate directly with increasing threat levels to tomato crops. Early detection at the egg or first-instar stage offers the best opportunity for non-chemical intervention.

Practical Usage: Monitoring and Management in Home Gardens

While \"using\" tomato bugs isn't a culinary concept, understanding their development enables proactive crop protection—a vital skill for anyone growing fresh tomatoes for kitchen use. Preventative measures should align with each stage of the insect’s life cycle.

- Egg Stage (Days 1–7): Inspect undersides of leaves weekly, especially along midribs and near flower clusters. Eggs are often laid in symmetrical rows and can be removed manually using tweezers or a damp cloth. Introduce natural predators like parasitic wasps (Trichopoda pennipes) or lacewings, which lay eggs inside stink bug ova.

- Early Nymph Stage (Days 8–20): Apply insecticidal soap or neem oil sprays early in the morning when nymphs are least active. Avoid broad-spectrum pesticides to preserve beneficial insects. Encourage biodiversity by planting nectar-rich borders (e.g., yarrow, dill) to attract assassin bugs and predatory beetles.

- Late Nymph Stage (Days 21–40): Monitor for increased leaf stippling and fruit dimpling. Use sticky traps or beat sheets beneath plants to detect population density. Hand-picking remains effective if infestations are localized.

- Adult Stage (Day 40+): Deploy pheromone traps to capture mating adults. Consider row covers during peak flight periods (late spring to early fall). Remove plant debris post-harvest to eliminate overwintering sites.

Tip: Rotate inspection times daily—nymphs often hide during midday heat. Use a magnifying lens to distinguish tomato bug eggs from those of beneficial species like lady beetles, which have elongated, upright forms rather than barrel shapes.

Variants & Types of Tomato-Feeding Bugs

Although often grouped under “tomato bug,” several distinct species exhibit similar behaviors and appearances. Accurate identification informs more precise control methods:

- Green Stink Bug (Acrosternum hilare): Bright green, lacks shoulder markings. Feeds aggressively on fruit sap, transmitting bacterial pathogens like Pseudomonas syringae. Common across North America.

- Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (Halyomorpha halys): Invasive species with marbled brown coloring and white-banded antennae. Highly polyphagous, attacks tomatoes late season. Known for overwintering indoors.

- Red-Shouldered Stink Bug (Thyanta custator): Smaller than other species, features distinctive red-orange pronotal shoulders. Prefers solanaceous hosts and is prevalent in southern and central U.S.

- Leaf-Footed Bug (Leptoglossus phyllopus): Not a true stink bug but causes comparable damage. Named for flattened, leaf-like hind tibiae. Often mistaken for tomato bugs despite different taxonomy.

Among these, Thyanta custator represents the most accurate biological referent to the colloquial “tomato bug.” Its narrow host range makes it easier to manage via crop rotation compared to generalist feeders like Halyomorpha halys.

Comparison with Similar Insects

Misidentification leads to ineffective treatments. Below is a comparison highlighting key differences between tomato bugs and commonly confused species:

| Insect | Body Shape | Coloration | Wings | Distinguishing Feature | Damage Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato Bug (Thyanta custator) | Shield-shaped, oval | Green with red shoulders | Fully developed in adult | Red markings on pronotum | Small, sunken spots on green fruit |

| Lady Beetle (Ladybug) | Dome-shaped, rounded | Red with black spots | Hardened elytra (beetle) | Circular body, short legs | Beneficial predator—no plant damage |

| Aphids | Oblong, soft-bodied | Green, black, or yellow | None (wingless); some winged forms | Cluster on new growth, secrete honeydew | Curling leaves, sooty mold |

| Spider Mites | Microscopic, eight-legged | Red or pale yellow | No wings | Webbing on leaf undersides | Speckled foliage, bronzing |

| Leaf-Footed Bug | Long, narrow | Brown-gray | Fully winged | Flattened hind legs | Large necrotic patches on ripe fruit |

This differentiation is crucial when applying biological controls. For example, releasing lacewings will suppress aphids and mite eggs but has limited effect on later-stage stink bugs.

Practical Tips & FAQs

What time of year do tomato bugs appear?

Adults emerge from overwintering shelters (leaf litter, bark, structures) in early spring. Egg-laying begins in late May to June, coinciding with tomato flowering. A second generation often emerges in late summer, posing risk to late-season harvests.

Can I eat tomatoes damaged by tomato bugs?

Yes, but with caution. Superficial feeding marks (catfacing) can be cut away. However, deep punctures introduce molds and bacteria. Discard fruit showing internal browning, off odors, or mushiness. Cooking does not neutralize all microbial risks from contaminated tissue.

Are there resistant tomato varieties?

Some cultivars show moderate resistance. Indeterminate types with hairy foliage (e.g., ‘Matt’s Wild Cherry’, ‘Ponderosa’) tend to deter oviposition. Heirloom beefsteaks are generally more vulnerable due to thinner skin and higher sugar content.

How do I store harvested tomatoes to avoid attracting bugs?

Store ripe tomatoes in a cool, dry place away from windows or exterior doors. Do not leave them outdoors overnight. Refrigeration slows ripening and reduces volatile emissions that attract adult stink bugs seeking food sources.

Do tomato bugs bite humans?

No. They do not feed on blood or flesh. However, they may probe bare skin defensively, causing mild irritation. Their primary defense mechanism is chemical secretion, which can stain surfaces and produce an unpleasant odor.

Is organic control possible without sacrificing yield?

Yes, with consistent effort. Combine cultural practices—such as trap cropping with highly attractive plants like sunflowers or millet—with mechanical removal and botanical sprays. Research from the University of Florida IFAS Extension shows that farms using diversified IPM reduce stink bug damage by up to 70% without synthetic insecticides.

Expert Insight: “Monitoring egg masses weekly can reduce your need for sprays by 80%. Once you see the red-orange first instars, act fast—they’re vulnerable for only 48 hours before molting.” — Dr. Elena Rodriguez, Entomologist, NC State Extension

Summary & Key Takeaways

The development of the tomato bug unfolds in three principal stages—egg, nymph, and adult—each presenting unique challenges for growers. Recognizing these phases empowers timely, ecologically sound responses that protect both plant health and harvest integrity.

- The egg stage lasts 4–7 days and appears as clustered, barrel-shaped units on leaf undersides.

- Nymphs progress through five instars over 3–5 weeks, transitioning from bright red-orange to gray-green with developing wing pads.

- Adults are mobile, shield-shaped insects measuring up to 15 mm, identifiable by red shoulder markings in true tomato bugs.

- Damage includes fruit dimpling, seed cavity discoloration, and increased susceptibility to rot.

- Effective management combines scouting, biological controls, and selective interventions aligned with developmental timing.

- Accurate identification prevents misapplication of treatments and preserves beneficial insect populations.

Understanding the tomato bug’s life cycle transforms pest management from reactive crisis response to strategic prevention. Whether you cultivate a single patio pot or manage acres of heirloom tomatoes, this knowledge ensures healthier plants, cleaner harvests, and superior ingredients for your kitchen.

Take Action: Begin a weekly scouting log this season. Note dates of first egg sightings, nymph emergence, and adult captures. Over time, this data will refine your intervention schedule and improve long-term garden resilience.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?