Synchronized light shows transform ordinary spaces into immersive experiences—whether it’s a backyard holiday display, a community festival installation, or a professional stage production. But achieving true synchronization—where lights pulse, fade, chase, and flash in precise alignment with music or cues—is less about magic and more about methodical execution. It requires understanding the interplay between hardware capabilities, timing protocols, software logic, and human perception. This guide distills years of field experience from lighting designers, hobbyist engineers, and live-event technicians into a grounded, actionable roadmap. No assumptions about prior coding or electronics knowledge—just clear progression from concept to execution.

1. Define Your Scope and Select Hardware Strategically

Before writing a single line of code or plugging in a controller, define the physical and experiential boundaries of your show. Ask: How many fixtures? What types (LED strips, bulbs, moving heads)? Where will they be placed? What’s the maximum distance between controller and farthest light? And crucially—what level of responsiveness do you need? A 30-light porch display has vastly different requirements than a 200-fixture warehouse installation with millisecond-level beat detection.

Hardware selection isn’t about buying the most expensive gear—it’s about matching capability to purpose. Start with three foundational components:

- Controllers: Choose based on protocol support (DMX-512, E1.31/Art-Net, or proprietary like ESPixelStick). For beginners, ESP32-based controllers running WLED offer intuitive web interfaces and built-in audio-reactive modes. For larger setups, consider Raspberry Pi 4s running xLights or Falcon Player (FPP) for robust scheduling and multi-universe DMX output.

- Lighting Fixtures: Prioritize addressable LEDs (e.g., WS2812B, SK6812) with consistent voltage tolerance and refresh rates ≥400 Hz. Avoid mixing brands without verifying timing compatibility—subtle differences in signal interpretation cause flicker or desynchronization.

- Power & Wiring: Calculate total wattage at peak brightness (not nominal), then add 20% headroom. Use thick-gauge wire (12–14 AWG) for runs over 5 meters. Always inject power every 2–3 meters on long LED strips to prevent voltage drop—and test each segment independently before full integration.

2. Set Up Software and Establish Timing Infrastructure

Software is where intention becomes instruction. The industry standard for hobbyist-to-professional light show programming is xLights—free, open-source, and actively maintained. Its strength lies in frame-accurate sequencing, audio waveform visualization, and export flexibility across platforms (FPP, Raspberry Pi, E681, etc.). Alternatives like Vixen 3 or Light-O-Rama work well but lack xLights’ granular timing controls and active community support.

Timing is the backbone of synchronization. All modern light show software relies on a shared temporal reference: the frame. A frame is a discrete time slice—typically 50 ms (20 fps) for most displays. Every action (fade, color shift, intensity ramp) must be scheduled to begin and end on exact frame boundaries. Why? Because human vision perceives changes below ~30 ms as continuous motion; inconsistent frame alignment creates perceptible “drag” or “stutter,” especially during fast chases or strobes.

To establish reliable timing:

- Configure your computer’s audio driver for low-latency operation (ASIO on Windows, Core Audio on macOS). Disable all background audio enhancements.

- In xLights, set “Frame Rate” to match your target (20 fps is ideal for balance of smoothness and CPU load).

- Enable “Audio Sync Mode” and verify waveform playback aligns precisely with exported audio files (use a metronome track to test).

- Assign each controller a unique IP address and configure its network settings to match your show’s subnet—no DHCP drift.

“Synchronization fails not because of bad code, but because of unmanaged latency. Every hop—from audio buffer to controller firmware to LED response—adds microseconds. At scale, those microseconds become frames.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Embedded Systems Researcher, UC San Diego

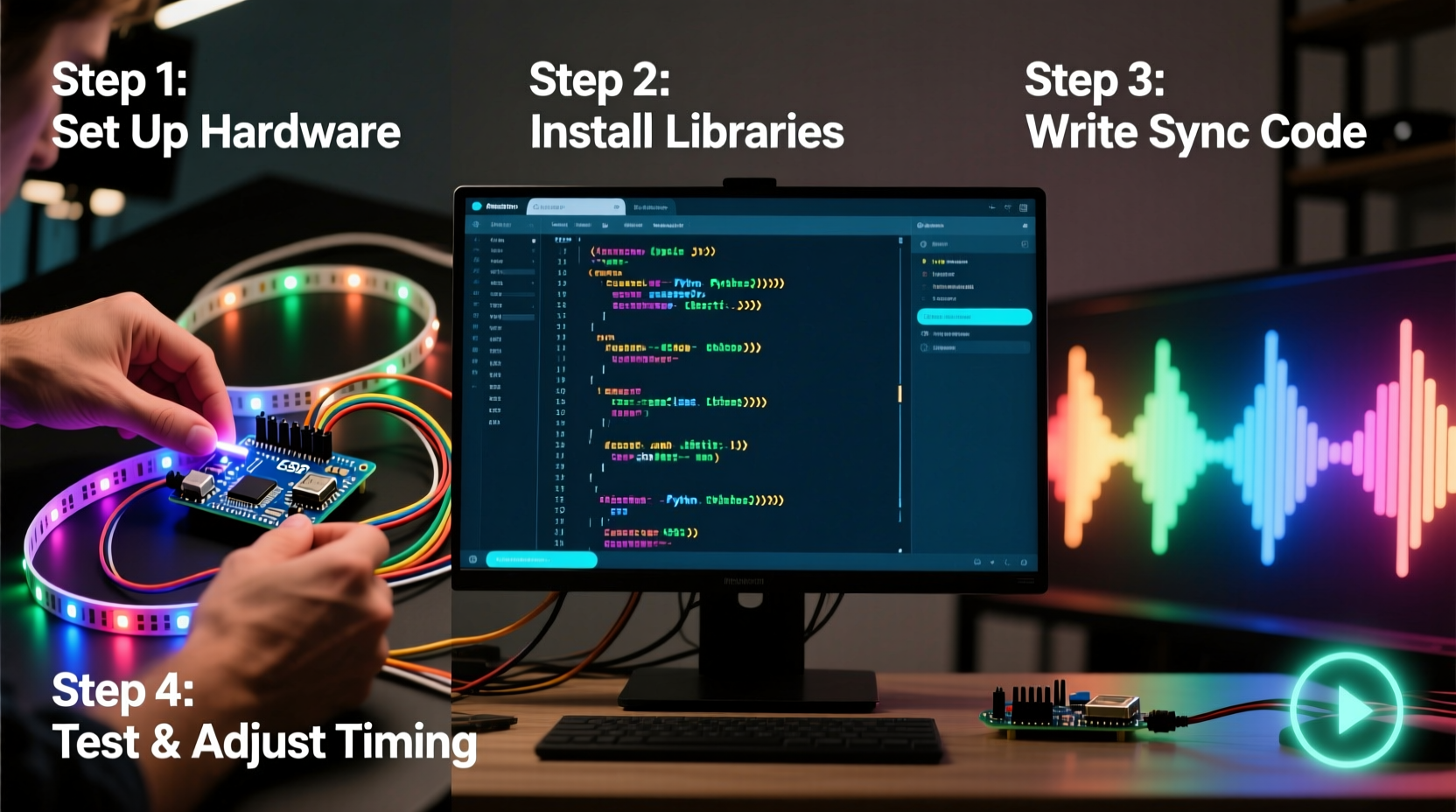

3. Build Your First Synchronized Sequence (Step-by-Step)

This is where theory meets practice. Follow this sequence exactly—no shortcuts—to internalize the rhythm of synchronized programming:

- Import and Prepare Audio: Load your track (.wav preferred, 44.1 kHz, 16-bit). Trim silence, normalize peaks to -3 dB, and export as a new file. In xLights, right-click the audio track and select “Analyze Audio” to generate beat and intensity data.

- Create a Model: Right-click the Layout tab → “Add Model” → “RGB Lights” → “Strip”. Name it “Front Porch Left”, set pixel count (e.g., 50), and assign to Universe 1, Channel 1. Repeat for each physical strip—mirroring your real-world layout.

- Build a Timeline: Drag the audio track to the timeline. Zoom to 1-second intervals. Place your first effect at 0:00:00.000—exactly on the downbeat. Use the “Effect Palette” → “Color Fade” → set start color (white), end color (red), duration = 2 seconds (40 frames). Ensure “Start on Frame Boundary” is checked.

- Add Beat Sync: At 0:00:02.000, insert a “Strobe” effect. Right-click the strobe → “Edit Effect” → under “Timing”, select “Sync to Beat” and choose “Strong Beat” from the analysis. Set strobe duration to 0.1 seconds (2 frames) and intensity to 100%.

- Test Output: Click “Play Preview” (spacebar). Watch the waveform and timeline cursor move in lockstep. If the strobe lags, check audio analysis accuracy—re-analyze or manually adjust beat markers using the waveform editor.

- Export and Deploy: Go to Tools → Export → “Export to FPP” (or your controller platform). Select all models, set output rate to match your controller’s refresh limit (e.g., 400 Hz), and deploy via SCP or web interface.

4. Real-World Integration: Audio, Triggers, and Environmental Factors

A backyard show faces challenges no studio does: wind, rain, temperature swings, and Wi-Fi interference. A 2023 case study by the Midwest Holiday Lighting Collective illustrates this. Their annual “Winter Lights Trail” used 187 controllers across 1.2 miles of outdoor path. Initial tests showed 12% of strips desynchronizing after 15 minutes—traced not to software, but to voltage sag in sub-zero conditions causing microcontroller clock drift.

Their solution was threefold:

- Switched all power supplies to industrial-grade units with wide-temp rating (-30°C to +60°C).

- Added local timing references: Each controller ran an NTP client synced to a Raspberry Pi master clock, correcting drift every 30 seconds.

- Replaced Wi-Fi control with wired Ethernet where possible, and for wireless segments, implemented UDP packet checksums and retransmission timeouts.

This highlights a critical principle: synchronization isn’t just software—it’s a stack. Consider these environmental integrations:

| Factor | Impact on Sync | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Ambient Temperature | LED driver ICs slow at <0°C; capacitors leak at >40°C, affecting timing circuits | Use industrial-rated controllers; insulate outdoor enclosures with silica gel desiccant |

| Wi-Fi Congestion | UDP packet loss causes missing frames; >3% loss degrades sync visibly | Operate on 5 GHz band with fixed channel; use directional antennas; implement forward error correction (FEC) in firmware |

| Audio Source Quality | Compressed MP3s lose transient detail needed for accurate beat detection | Always sequence using lossless .wav; convert to MP3 only for final playback |

| Electrical Noise | EMI from motors or dimmers induces glitches in data lines | Use shielded twisted-pair cable (e.g., CAT6) for data; separate power and data runs by ≥12 inches |

5. Troubleshooting Desynchronization: A Diagnostic Checklist

When lights fall out of sync, resist the urge to rewrite sequences. Most issues are systemic—not artistic. Use this checklist before touching code:

- ✅ Verify all controllers report identical time (via NTP or manual ping test)

- ✅ Confirm audio playback device uses exclusive mode (no other app sharing the buffer)

- ✅ Check controller firmware version matches software expectations (e.g., FPP v4.4 requires xLights v2023.12+)

- ✅ Test one model alone—does sync hold? If yes, isolate conflicting models (overloaded universes cause dropped packets)

- ✅ Monitor CPU usage during preview: sustained >85% indicates insufficient processing headroom—reduce frame rate or effects density

Common symptoms and their root causes:

- Lag that worsens over time: Clock drift—controllers losing nanoseconds per second. Fix: Enable NTP sync or use a GPS-disciplined oscillator for master clock.

- Random “jumps” mid-show: Network packet corruption. Fix: Switch to wired connection or upgrade to 802.11ax (Wi-Fi 6) with OFDMA for deterministic scheduling.

- Beat effects misaligned by half a beat: Audio analysis error—especially common with bass-heavy tracks where kick drums mask snare transients. Fix: Manually place beat markers using the waveform zoom tool (Ctrl+Scroll); disable auto-analysis for complex genres.

FAQ

Do I need to write code to program a synchronized light show?

No—modern tools like xLights, Light-O-Rama, and WLED provide visual sequencers and drag-and-drop interfaces. You’ll configure timing, effects, and channels through GUIs. However, understanding basic concepts like frame rate, universes, and DMX addressing is essential. Only advanced customizations (e.g., generative patterns, sensor input) require Python or C++ scripting.

Can I sync lights to live microphone input instead of pre-recorded audio?

Yes—but with caveats. Real-time audio sync introduces 50–200 ms of latency depending on buffer size and processing. For casual use (e.g., party lights), WLED’s built-in microphone mode works well. For performance-critical applications (e.g., DJ booth lighting), use dedicated hardware like the Enttec Open DMX USB with FFT analysis firmware, and accept that perfect lip-sync is physically unattainable due to sound propagation delay.

How many lights can one Raspberry Pi control reliably?

A Raspberry Pi 4 (4GB RAM) running FPP can output up to 8 universes (4096 channels) at 40 fps with simple effects. With intensive effects (e.g., per-pixel noise, physics-based ripples), reduce to 4 universes or lower frame rate. For >10,000 pixels, distribute across multiple Pis—one as master scheduler, others as slave renderers.

Conclusion

Programming a synchronized light show is fundamentally an act of disciplined translation: converting emotion, rhythm, and narrative into precise electrical signals timed to the microsecond. It’s engineering dressed as artistry—where every frame matters, every volt counts, and every decision echoes in the viewer’s peripheral vision. You don’t need a lab or a budget—just clarity of intent, respect for timing fundamentals, and willingness to test, measure, and refine. Start small: synchronize three lights to one bar of music. Get that right. Then add three more. Then a fade. Then a beat. Watch how intention crystallizes into coherence—and how coherence becomes wonder.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?