At first glance, teeth and bones appear to be made of similar materials—both are hard, white, and rich in calcium. It’s no wonder many people assume teeth are a type of bone. However, from a biological and structural standpoint, teeth and bones are fundamentally different. Understanding these distinctions isn’t just academic; it affects how we care for our bodies, treat injuries, and approach dental health. This article breaks down the science behind teeth and bones, highlighting their unique properties, functions, and limitations.

Anatomical and Structural Differences

While both teeth and bones contain calcium phosphate and collagen, their internal structures diverge significantly. Bones are living tissues composed of cells called osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts that continuously remodel throughout life. This dynamic process allows bones to heal, adapt to stress, and regulate mineral balance in the body.

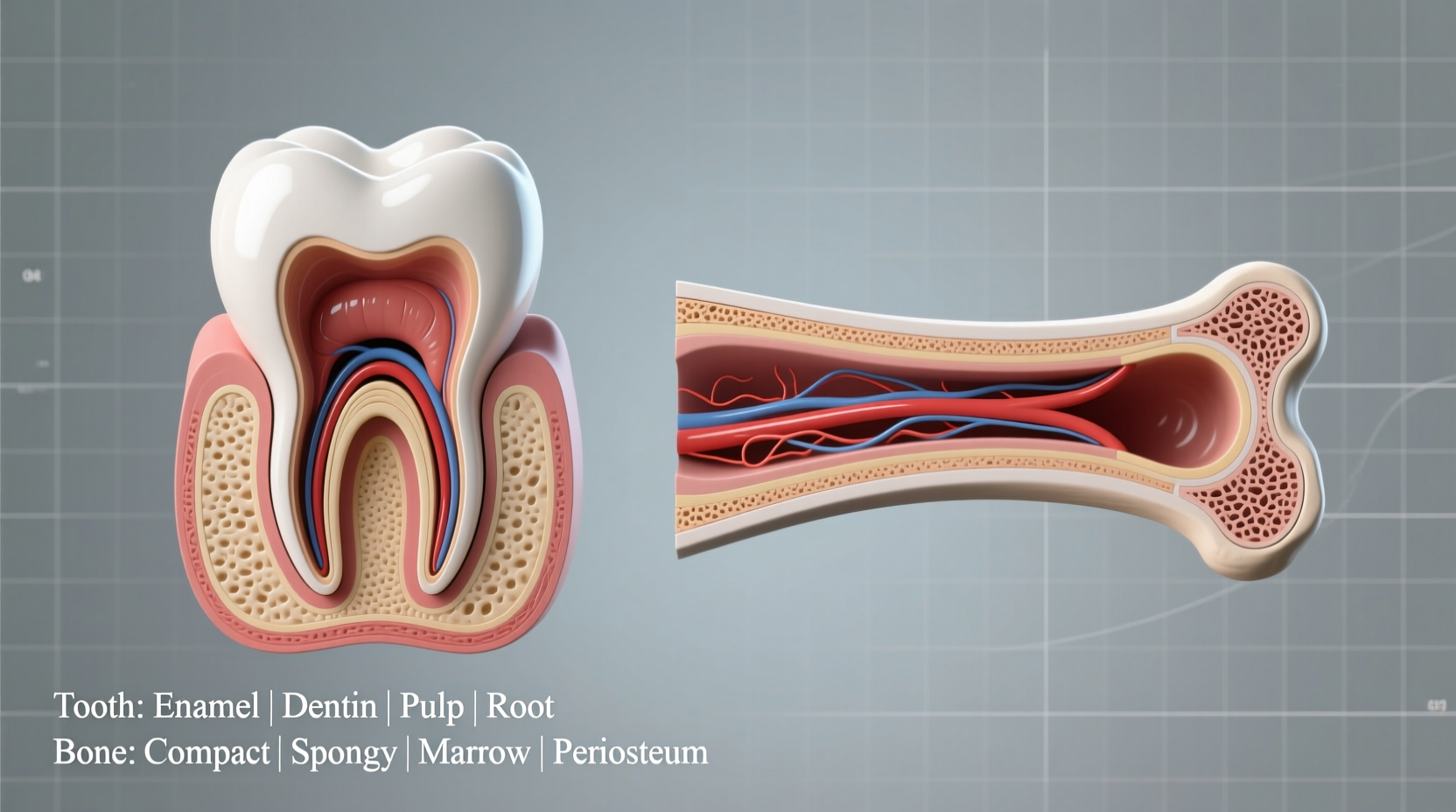

In contrast, teeth consist of multiple layers—enamel, dentin, cementum, and pulp—but lack the regenerative cellular network found in bones. Enamel, the outermost layer, is the hardest substance in the human body but contains no living cells. Once damaged, enamel cannot regenerate. Dentin, beneath the enamel, is softer and contains microscopic tubules connected to the nerve-rich pulp at the core.

Bones are surrounded by a vascular membrane called the periosteum, which supplies blood and nerves essential for healing. Teeth have a similar outer covering—the periodontal ligament—but rely on the pulp and surrounding gum tissue for nutrients. Unlike bones, teeth do not have a direct blood supply once fully developed, limiting their ability to respond to injury.

Regeneration and Healing Capabilities

One of the most critical distinctions between teeth and bones lies in their ability to heal. When a bone fractures, the body initiates a complex repair process. Blood clots form at the break, stem cells migrate to the site, and new bone tissue gradually replaces the damaged area. Full recovery can take weeks to months, but complete regeneration is possible.

Teeth, however, cannot self-repair in the same way. A chipped or cracked tooth does not grow back. While dentin can slowly deposit secondary layers in response to minor damage—a process known as tertiary dentinogenesis—this is limited and insufficient to mend significant injuries. Cavities caused by bacteria erode enamel and dentin irreversibly. Without intervention, decay spreads to the pulp, leading to infection or abscess.

This lack of regenerative capacity underscores the importance of preventive dental care. Unlike broken bones, which often heal with time and immobilization, damaged teeth require professional treatment such as fillings, crowns, or root canals.

“Teeth are marvels of biological engineering, but they’re not built to regenerate like bones. Once enamel is gone, it’s gone for good.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Oral Biologist and Researcher at Columbia University School of Dental Medicine

Functional Roles in the Body

Bones serve multiple roles: supporting the body, protecting organs, enabling movement through muscle attachment, storing minerals (especially calcium and phosphorus), and producing blood cells in the marrow. The skeletal system is dynamic, responsive, and integrated into the body’s metabolic processes.

Teeth, on the other hand, are specialized for mechanical processing of food. Their primary function is mastication—breaking down food into smaller particles for digestion. They also play roles in speech articulation and facial structure support. Unlike bones, teeth do not contribute to hematopoiesis or systemic mineral regulation.

Another key difference is turnover rate. Bone tissue renews itself approximately every 10 years through resorption and formation. Teeth, once fully developed, remain structurally unchanged unless altered by disease, wear, or trauma. This static nature makes long-term oral hygiene essential.

Key Functional Differences Summary

| Feature | Bones | Teeth |

|---|---|---|

| Living Tissue? | Yes – constantly remodeling | No – minimal cell activity after development |

| Healing Ability | Full regeneration possible | Limited; no enamel repair |

| Primary Function | Support, protection, movement, mineral storage | Chewing, speech, aesthetics |

| Turnover Rate | ~10 years | None after maturation |

| Blood Supply | Rich via periosteum and marrow | Only through pulp and gums |

Misconceptions and Real-World Implications

A common misconception is that because teeth and bones share a chalky appearance and mineral content, they should be cared for similarly. This leads some to neglect dental hygiene, assuming that “strong bones mean strong teeth.” But nutrition alone doesn’t guarantee dental health. For example, vitamin D and calcium support both systems, but sugar intake disproportionately harms teeth due to bacterial fermentation in the mouth.

Mini Case Study: Sarah, a 32-year-old fitness instructor, maintained excellent bone density through diet and weight training. Despite her healthy lifestyle, she developed multiple cavities due to frequent consumption of sports drinks. The acidity and sugar eroded her enamel over time. Her dentist explained that while her bones were robust, her teeth lacked the biological defenses to combat constant acid exposure. Adjusting her hydration habits and increasing fluoride use reversed further damage.

This case illustrates that systemic health doesn’t automatically translate to oral health. Teeth require targeted care strategies distinct from those used for bones.

Preventive Care Checklist

- Brush twice daily with fluoride toothpaste

- Floss daily to remove plaque between teeth

- Limit sugary and acidic foods and beverages

- Use a mouthguard if you grind your teeth at night

- Schedule dental checkups every six months

- Rinse with water after meals when brushing isn’t possible

- Consider dental sealants for added protection, especially in children

Frequently Asked Questions

Are teeth stronger than bones?

Enamel, the outer layer of teeth, is harder than bone on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness. However, this doesn’t make teeth “stronger” overall. Enamel is brittle and prone to cracking under pressure, whereas bone is more flexible and impact-resistant due to its collagen matrix.

Can teeth heal themselves like bones?

No. While bones regenerate through cellular activity, teeth cannot regrow enamel or repair large structural damage. Minor remineralization can occur on the surface of enamel through fluoride and saliva, but this is not true healing.

Why do we say teeth are not bones if they look so similar?

Appearance can be misleading. Though both are calcified and white, teeth lack bone’s living cellular structure, blood vessels, marrow, and regenerative abilities. They are anatomically classified as separate organs with unique developmental origins.

Conclusion: Why This Distinction Matters

Recognizing that teeth are not bones transforms how we approach oral health. It shifts the focus from passive assumptions (“I eat well, so my teeth are fine”) to active prevention. Unlike bones, which benefit from general wellness, teeth demand consistent, specialized care. Ignoring this distinction risks preventable issues like decay, gum disease, and tooth loss.

Your skeleton will rebuild itself over time. Your teeth won’t. Every brushing, flossing session, and dental visit is an investment in preserving a non-renewable resource. Treat your smile with the precision it deserves.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?