Many home cooks reach for an onion without considering the variety in their hand, assuming all onions are interchangeable. Yet, choosing between a long onion and a regular (bulb) onion can dramatically affect the flavor, texture, and authenticity of a dish. While both belong to the Allium family and share pungency and aroma, their structural form, chemical composition, and culinary roles diverge significantly. Understanding these differences isn't just botanical curiosity—it's essential for achieving balanced taste and proper technique, especially in regional cuisines where specific onion types define traditional flavors. This guide breaks down the distinctions in structure, taste, usage, and substitution potential, empowering you to make informed choices in everyday cooking.

Definition & Overview

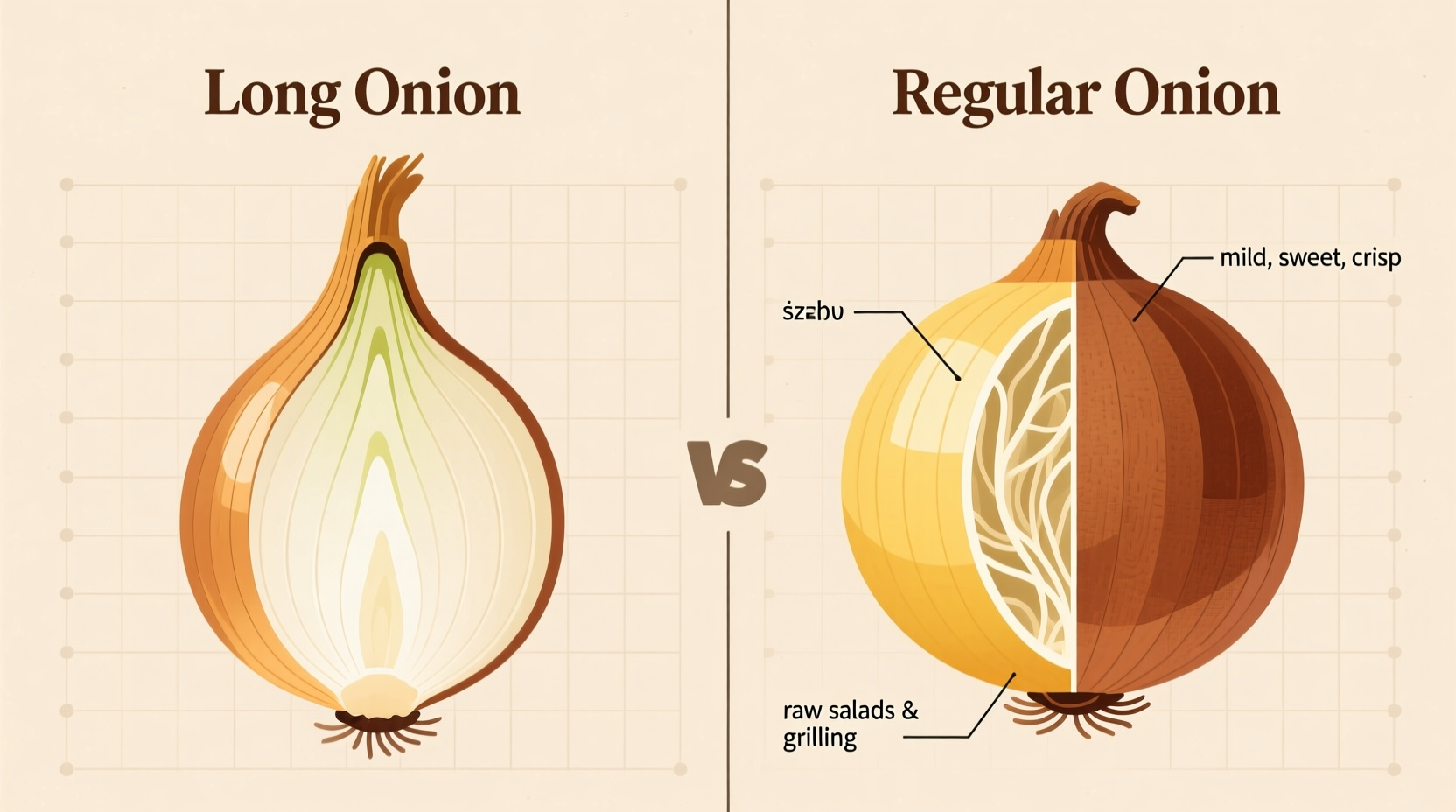

Long onions, often referred to as scallions, green onions, spring onions, or salad onions depending on region and maturity, are young, immature members of the Allium fistulosum or Allium cepa species. They feature elongated green stalks with a small, barely developed white bulb at the base. Harvested early, they are prized for their crisp texture and mild, fresh onion flavor.

Regular onions, also known as bulb onions or storage onions, come primarily from the Allium cepa species. These mature into large, layered bulbs with thick, papery skin. Available in yellow, red, and white varieties, they are cultivated for longer shelf life and deeper, more complex flavor profiles that develop through cooking. Unlike long onions, regular onions undergo full maturation, resulting in higher sulfur compound concentration, which contributes to their sharpness and tear-inducing qualities.

While both are used globally, their applications differ by cuisine and preparation method. Confusing the two can lead to overly pungent salads, under-seasoned stir-fries, or textural imbalances in soups and sauces.

Key Characteristics

| Characteristic | Long Onion | Regular Onion |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Allium fistulosum or immature A. cepa | Allium cepa |

| Form & Structure | Elongated green stalk; slender white base, no dense bulb | Dense, round bulb with concentric layers |

| Flavor Profile | Mild, fresh, slightly sweet with subtle bite | Pungent, sharp when raw; sweetens with cooking |

| Aroma | Clean, grassy, faintly sulfurous | Strong, acrid, high in volatile sulfur compounds |

| Texture | Crisp, juicy, tender (both green and white parts) | Firm, fibrous when raw; softens and breaks down when cooked |

| Shelf Life | 5–7 days refrigerated, best used fresh | 2–3 months when stored in cool, dry conditions |

| Culinary Function | Raw garnish, quick-cook aromatics, color and freshness | Base for sautéing, caramelizing, stewing, roasting |

Practical Usage: How to Use Each Onion Type

Long Onions in Cooking

Due to their delicate nature and mild flavor, long onions excel in applications where freshness and visual appeal matter. The entire stalk—white base and green top—is typically used, though the very dark green tips may be trimmed if fibrous.

- Raw Applications: Sliced thinly over tacos, rice bowls, noodle dishes, or salads. Their crunch adds contrast without overwhelming other ingredients.

- Quick-Cook Dishes: Added in the final minutes of stir-fries, omelets, or soups to preserve texture and color.

- Garnishing: Chopped green onions finish pho, ramen, dim sum, or baked potatoes, contributing both flavor and vibrant green hue.

- Marinades & Dressings: Finely minced, they infuse vinaigrettes or yogurt sauces with onion essence without harshness.

In East and Southeast Asian kitchens, long onions are foundational. In Chinese cuisine, they're part of the “aromatic trio” with garlic and ginger, sautéed briefly to build flavor without browning. Japanese chefs use them in miso soup and atop okonomiyaki. Korean kimchi sometimes includes chopped scallions for added bite.

Regular Onions in Cooking

Bulb onions serve as the backbone of countless savory dishes. Their ability to transform under heat makes them indispensable in professional and home kitchens alike.

- Sautéing & Sweating: Yellow onions are most commonly used here. Cooked slowly in fat, they release sugars and become translucent, forming the flavor base for sauces, stews, and curries.

- Caramelizing: A slow process (30–45 minutes) that converts natural sugars into deep, umami-rich compounds. Ideal for French onion soup, burgers, or pizza toppings.

- Roasting & Grilling: Whole or halved onions caramelize in the oven or on the grill, developing smoky sweetness. Pairs well with meats and root vegetables.

- Raw Uses: Thinly sliced red onions add color and sharpness to salsas, sandwiches, and ceviche. Soaking in cold water or vinegar reduces their bite.

- Pickling: White onions are preferred for quick pickles due to their crisp texture and neutral flavor, common in Mexican and Middle Eastern dishes.

Pro Tip: When building flavor layers, start with regular onions as your aromatic base. Add long onions at the end for freshness and texture. Never substitute one for the other in equal measure during critical stages—doing so alters moisture content, cooking time, and flavor intensity.

Variants & Types

Types of Long Onions

- True Scallions (Allium fistulosum): No bulb formation, consistent thin stalk. Most common in Asia.

- Spring Onions: Immature bulb onions pulled early; have a small, rounded bulb and green tops. Slightly stronger than scallions.

- Welsh Onions: A perennial variety, often grown in gardens. More robust flavor, excellent for cooking.

- Salad Onions: Commercial term for small, round-bulbed onions with long greens, milder than mature bulbs.

Types of Regular Onions

- Yellow Onions: Most versatile; high in sulfur and sugar. Best for cooking. Makes up 80% of onion sales in the U.S.

- White Onions: Crisper, milder when raw. Common in Mexican cuisine for salsas and grilled dishes.

- Red Onions: Contain anthocyanins (natural pigments), giving them purple skin and flesh. Used raw for color and moderate sharpness.

- Shallots: Technically a separate Allium species (A. cepa var. aggregatum). Milder, sweeter, with fine layers. Preferred in French and Thai cooking.

- Spanish Onions: Large, mild, high-water-content yellow onions. Often eaten raw in sandwiches or burgers.

Each variant serves a purpose. For example, red onions are rarely caramelized—they lose color and turn muddy—but shine in raw applications. White onions are favored in authentic tacos because they don’t overpower lime and cilantro.

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Confusion often arises not just between long and regular onions, but among related alliums. Here’s how they compare:

| Ingredient | vs. Long Onion | vs. Regular Onion |

|---|---|---|

| Shallot | More intense flavor than long onion; never used as garnish | Milder, sweeter, less fibrous than yellow onion; better for fines herbes or vinaigrettes |

| Leek | Larger, thicker stalk; requires thorough cleaning; milder, earthier | Used like long onion in soups but needs longer cooking; not a direct substitute |

| Chives | Grass-like, very delicate; only green part used; floral onion note | No bulb; strictly garnish; cannot replace either in cooking |

| Garlic Scapes | Also long and green, but curly and harvested from garlic plants | Not a bulb-former; used like long onion in stir-fries but with garlicky punch |

“In Thai curry pastes, we use only shallots and garlic—never bulb onions. But for finishing a boat noodle soup, fresh-sliced long onions are non-negotiable. The balance of cooked depth and raw brightness defines the dish.” — Chef Niran Rerkkittiwong, Bangkok Street Food Authority

Practical Tips & FAQs

Can I substitute long onions for regular onions?

Only partially and contextually. You’d need about 6–8 long onions to match the volume of one medium bulb onion, but the flavor will be much milder. Not suitable for recipes requiring long cooking or significant sweetness development. Best reserved for last-minute additions or raw use.

Can I use regular onions in place of long onions?

Not effectively. Raw bulb onions are too strong and crunchy for garnishes. If long onions are unavailable, blanch sliced yellow onion for 30 seconds and chill to reduce sharpness, or use very finely minced red onion soaked in ice water.

How should I store each type?

Store long onions wrapped in a damp paper towel inside a plastic bag in the refrigerator crisper drawer. Use within a week. Regular onions require cool, dark, dry ventilation—never refrigerate unless cut. Avoid storing near potatoes, which emit ethylene gas and accelerate sprouting.

Which is healthier?

Both offer benefits. Long onions provide vitamin K, C, and antioxidants in their green parts. Regular onions contain quercetin, a flavonoid with anti-inflammatory properties, concentrated in the outer layers. Red onions have the highest antioxidant content. Cooking preserves most nutrients, though some vitamin C is lost.

Why do long onions sometimes have a pink tinge at the base?

This is normal in spring onions and indicates youth, not spoilage. It results from anthocyanin pigments and disappears when cooked.

Do long onions make you cry?

Rarely. Because they’re harvested before full bulb development, they produce fewer lachrymatory-factor synthase enzymes—the compounds that trigger tears. Regular onions, especially yellow ones, are far more likely to cause eye irritation.

Storage Hack: Freeze chopped regular onions for cooking. They’ll soften when thawed but work perfectly in soups, stews, and sauces. Do not freeze long onions—they turn mushy and lose flavor.

Regional & Cultural Considerations

The distinction between long and regular onions carries cultural weight. In Indian cuisine, “onion” refers almost exclusively to the bulb type, used generously in curries and dals. Long onions appear mainly in street food like chaat or as a side garnish.

In contrast, Chinese recipes often specify cong (scallion) versus yang cong (Western onion). Substituting one for the other disrupts balance. Cantonese chefs use long onions in steamed fish and dumpling fillings, while bulb onions are avoided in delicate preparations.

Mexican cooking relies heavily on white bulb onions for raw applications but rarely uses long onions except as a garnish on certain antojitos. Meanwhile, Japanese households keep long onions on hand daily but use bulb onions sparingly, usually only in Western-style stews or hamburgers.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Understanding the difference between long onions and regular onions goes beyond botany—it’s fundamental to culinary precision. Long onions bring freshness, color, and mild bite, ideal for garnishes and quick-cook dishes. Regular onions deliver depth, sweetness, and structural integrity, forming the foundation of slow-cooked meals.

- Use long onions when you want freshness, crunch, and visual appeal—especially in Asian, Latin, and contemporary fusion dishes.

- Reach for regular onions when building flavor bases, caramelizing, roasting, or pickling.

- Never assume interchangeability. Their water content, fiber structure, and sulfur levels are too different for seamless substitution.

- Respect cultural context. Traditional recipes often depend on the correct onion type for authenticity.

- Store appropriately: Refrigerate long onions; keep bulb onions dry and ventilated.

Final Advice: Keep both types in rotation. Buy long onions weekly for freshness. Stockpile yellow and red bulb onions for versatility. Learning to distinguish their roles elevates your cooking from improvised to intentional—one slice at a time.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?