Spice is more than just heat—it’s a dimension of flavor that can elevate, transform, and define a dish. Yet many home cooks treat spiciness as an afterthought, adding chili flakes at the end or relying on bottled hot sauces without understanding how heat integrates into a recipe from the ground up. The true mastery of spice lies not in its intensity, but in its foundation. The “spicy flavor profile of bases” refers to how pungent, aromatic, and thermally active ingredients are introduced early in cooking to build depth, complexity, and balance. Understanding this concept separates competent cooking from truly dynamic cuisine.

In global culinary traditions—from Sichuan stir-fries to Ethiopian stews and Mexican moles—heat is rarely applied topically. Instead, it is woven into the fabric of the dish through base ingredients that are toasted, sautéed, fermented, or slow-cooked to unlock their full sensory potential. This article explores the science, technique, and strategy behind constructing a robust spicy foundation, offering practical guidance for building dishes where heat enhances rather than overwhelms.

Definition & Overview

The term spicy flavor profile of bases describes the intentional use of pungent ingredients during the initial stages of cooking to establish a layered, integrated heat that evolves throughout the dish. Unlike superficial applications of spice (such as garnishing with fresh chilies), base-level spicing involves incorporating heat sources into the aromatic foundation—typically alongside onions, garlic, ginger, or aromatics—that form the backbone of soups, sauces, curries, braises, and sautés.

This approach is central to numerous world cuisines. In Indian cooking, the tadka or tempering of whole spices in oil often includes dried red chilies. In Thai cuisine, curry pastes begin with pounding fresh chilies into a paste with lemongrass, galangal, and shrimp paste. In Creole and Cajun cooking, the “holy trinity” of onion, celery, and bell pepper may be joined by cayenne or paprika at the outset. These are not incidental additions—they are structural elements that shape the dish’s thermal architecture.

The goal is not simply to make food hot, but to create a flavor profile where heat contributes texture, aroma, and resonance. When done correctly, the spiciness becomes inseparable from the overall taste, emerging gradually with each bite rather than striking abruptly.

Key Characteristics of Spicy Bases

Spicy bases vary widely depending on culture, ingredient form, and cooking method, but they share several defining traits:

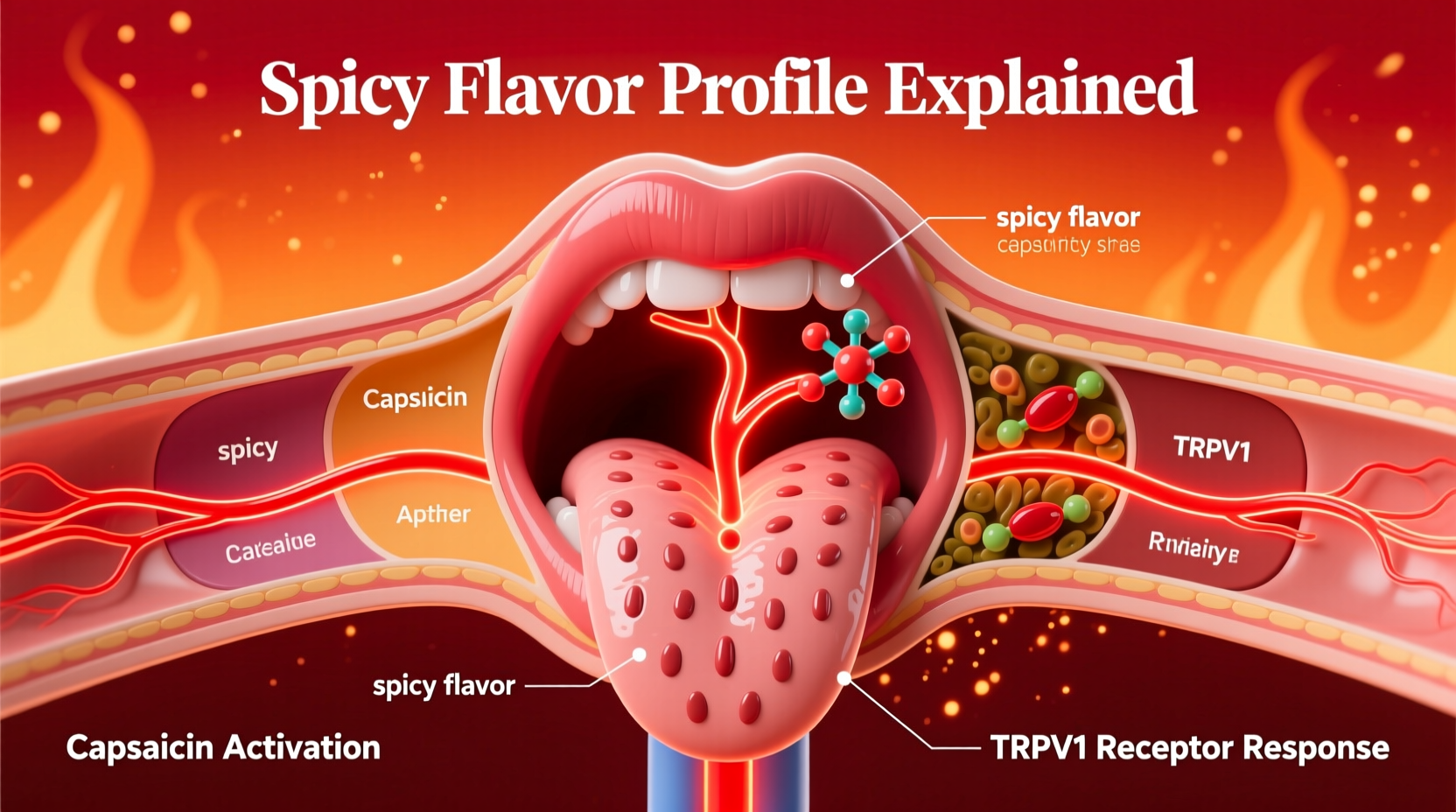

- Thermal Integration: Heat is developed during the foundational cooking phase, allowing capsaicin and other volatile compounds to disperse evenly.

- Aromatic Complexity: Spices release essential oils when heated in fat, producing fragrant compounds that interact with other ingredients.

- Layered Development: Multiple forms of heat (fresh, dried, fermented) may be combined to create multidimensional spiciness.

- Functional Role: Beyond pungency, spicy base ingredients contribute color, umami, bitterness, and even sweetness (as in smoked paprika).

- Stability: Once incorporated into a base, heat becomes stable and less prone to burning or fading during prolonged cooking.

| Characteristic | Description | Culinary Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Flavor Profile | Pungent, sharp, sometimes smoky or fruity | Adds dimension beyond mere heat |

| Aroma | Volatile, floral, earthy, or resinous when heated | Enhances nose and perceived richness |

| Color Contribution | Reds, oranges, deep browns (from chilies, paprika, etc.) | Imparts visual appeal and indicates flavor depth |

| Heat Level (Capsaicin Release) | Varies by ingredient; intensified by fat and time | Determines progression and balance of spiciness |

| Cooking Function | Sautéed, toasted, bloomed in oil, or blended into pastes | Structural role in flavor development |

| Shelf Life (Prepared Base) | Fresh: 3–5 days refrigerated; frozen: up to 3 months | Enables batch prep and consistent results |

Practical Usage: How to Build a Spicy Flavor Base

Constructing a successful spicy base requires attention to timing, temperature, and ingredient synergy. The following steps outline a universal framework applicable across cuisines:

- Select Your Heat Source(s): Choose one or more primary spicy ingredients based on desired effect—fresh chilies for brightness, dried for depth, fermented for funk, powdered for consistency.

- Prepare the Aromatic Trinity: Begin with a neutral base such as onion, shallot, garlic, and ginger. Sweat these gently in oil or ghee over medium-low heat until translucent but not browned.

- Bloom Dry Spices: Add ground spices like cayenne, smoked paprika, or chili powder to the fat and cook for 30–60 seconds, stirring constantly. This step, known as “blooming,” activates flavor compounds and removes raw notes.

- Incorporate Whole or Fresh Chilies: Add sliced fresh chilies or whole dried ones (e.g., arbol, guajillo) to infuse slowly. For pastes, blend ahead and add now.

- Build with Liquid: Deglaze with stock, coconut milk, or tomatoes to lock in flavors and prevent scorching.

- Simmer for Integration: Allow the mixture to simmer for 10–20 minutes so heat distributes evenly and melds with other components.

Pro Tip: Always bloom powdered spices in fat before adding liquids. Skipping this step leaves them tasting dusty and one-dimensional. A quick toast in oil transforms cayenne from sharp to resonant.

For example, consider a basic **red curry base**: blend 3–4 red Thai chilies, 1 stalk lemongrass (minced), 1-inch galangal, 3 cloves garlic, 1 shallot, and 1 tsp shrimp paste. Sauté this paste in coconut oil for 3–4 minutes until fragrant, then add coconut milk and simmer. The result is a rich, layered heat that unfolds gradually—first floral, then warming, finally lingering.

In contrast, a **Mexican adobo base** might involve rehydrating ancho and chipotle chilies, blending them with garlic, cumin, and oregano, then frying the puree in vegetable oil until thickened. This concentrated paste can be used immediately or stored, delivering deep, smoky heat ideal for braising meats or enriching beans.

Variants & Types of Spicy Bases

Spicy bases manifest differently across culinary traditions. Each variant reflects regional preferences, available ingredients, and cultural approaches to heat. Below are six major types, with guidance on usage:

- Curry Pastes (Southeast Asia): Blended mixtures of fresh chilies, aromatics, and herbs. Examples include Thai red, green, and Massaman curry pastes. Use: Stir-fries, soups, marinades. Best added early and fried briefly in oil.

- Tempered Spices (South Asia): Whole spices—including dried red chilies—fried in ghee or oil at the start or finish of cooking. Use: Dals, vegetable dishes, rice preparations. Adds sudden burst of fragrance and moderate heat.

- Adobos & Mojos (Latin America/Caribbean): Acid-forward blends using vinegar, citrus, and crushed chilies. Often marinated overnight. Use: Meat rubs, stew starters. Can be reduced into a base sauce.

- Roux-Based Heat (Cajun/Creole): Cayenne, paprika, or hot sauce incorporated into a roux (flour-fat mixture). Use: Gumbos, étouffées. Heat integrates structurally with thickening agent.

- Fermented Chili Bases (Korea, Ethiopia): Long-aged pastes like gochujang or berbere. Fermentation adds umami and mellows raw heat. Use: Stews, braises, condiments. Requires gentle heating to preserve complexity.

- Dry-Roasted Spice Mixes (Middle East/North Africa): Ground chilies combined with cumin, coriander, and caraway, dry-toasted before grinding. Use: Tagines, grain dishes, dips. Bloom again in oil before use.

| Type | Primary Ingredients | Best Used In | Heat Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thai Curry Paste | Fresh chilies, lemongrass, galangal | Curries, soups | Moderate to High |

| Indian Tadka | Dried red chilies, mustard seeds, cumin | Dals, vegetables | Low to Moderate |

| Mexican Adobo | Rehydrated chilies, garlic, vinegar | Mojo-marinated meats, salsas | Moderate (smoky) |

| Cajun Roux + Cayenne | Flour, oil, cayenne pepper | Gumbo, jambalaya | Medium, sustained |

| Korean Gochujang Base | Fermented chili paste, soy, rice syrup | Stir-fries, marinades | Medium (sweet-heat) |

| Ethiopian Berbere | Chili, fenugreek, cardamom, cloves | Doro wat, lentil stews | High, complex |

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Many cooks confuse spicy bases with standalone hot ingredients. Understanding the difference ensures proper application:

- Hot Sauce vs. Spicy Base: Hot sauce (e.g., Tabasco, sriracha) is typically added at the end or served on the side. It provides immediate heat but lacks integration. A spicy base is foundational and evolves with the dish.

- Chili Flakes vs. Toasted Chili Oil: Crushed red pepper sprinkled on pizza delivers surface heat. In contrast, chili oil—made by steeping chilies in hot oil—is a prepared base that infuses dishes from within.

- Raw Garlic + Chili vs. Cooked Paste: Raw combinations (like in some salsas) offer bright, aggressive heat. Cooking the same ingredients together mellows sharpness and creates harmony.

- Single Spice vs. Layered Base: Adding only cayenne to a stew yields flat heat. Combining cayenne with toasted onion, garlic, and smoked paprika builds dimensional warmth.

“The difference between amateur and professional heat management isn’t how much spice you use—it’s where and when you introduce it. A great spicy base doesn’t announce itself; it belongs.”

— Chef Elena Torres, Executive Chef, Mestiza Cocina

Practical Tips & FAQs

How do I control heat levels when building a base?

Start with less. You can always add more spice later, but you cannot remove it. Remove seeds and membranes from fresh chilies to reduce capsaicin load. For dried chilies, soak and taste before blending. Use mild paprika to dilute intense powders like cayenne.

Can I prepare spicy bases in advance?

Yes—and you should. Most aromatic-spice pastes freeze exceptionally well. Portion into ice cube trays, cover with oil, and freeze. Drop directly into pans when needed. Prepared bases keep refrigerated for up to five days or frozen for three months.

What fats work best for blooming spices?

Neutral oils (grapeseed, canola) allow spice flavors to shine. Coconut oil adds sweetness ideal for curries. Ghee or butter enhances richness and carries fat-soluble flavor compounds effectively. Avoid extra virgin olive oil for high-heat blooming due to low smoke point.

Why does my spicy base taste bitter?

Bitterness usually results from burning. Capsaicin and spice compounds degrade quickly at high temperatures. Always bloom spices over medium-low heat and stir constantly. If bitterness occurs, add a pinch of sugar or acid (lemon juice, vinegar) to counterbalance.

Are there non-chili sources of heat for bases?

Yes. Mustard seeds, black pepper, horseradish, wasabi, and ginger all contribute pungency without relying on capsaicin. In Scandinavian and Eastern European cuisines, mustard-based sauces serve as spicy foundations. Japanese wasabi-komi (a paste of wasabi and soy) functions similarly in sushi preparations.

How do I pair spicy bases with proteins and vegetables?

Match intensity to substance. Delicate fish works best with light, citrus-infused bases (e.g., Yucatán-style achiote). Heavier meats like lamb or beef stand up to robust, fermented bases like berbere or gochujang. Root vegetables absorb heat deeply; leafy greens benefit from quick sautéing with tempered chilies.

Storage Tip: Store homemade spicy bases in airtight containers under a thin layer of oil to prevent oxidation. Label with date and heat level (mild/medium/hot) for easy reference.

Can I substitute one spicy base for another?

With caution. While substitutions are possible, they alter flavor profiles significantly. Gochujang can replace harissa in a pinch, but expect sweetness instead of smokiness. Paprika-based roux can mimic adobo if smoked paprika and garlic are added, but lacks acidity. Always adjust seasoning after substitution.

Summary & Key Takeaways

The spicy flavor profile of bases is not about overwhelming the palate, but about embedding heat into the core structure of a dish. By treating spice as a foundational element—introduced early, cooked deliberately, and balanced thoughtfully—cooks achieve greater depth, control, and sophistication in their cuisine.

Key principles include:

- Introduce heat during the aromatic stage, not at the end.

- Bloom powdered spices in fat to activate flavor.

- Combine multiple forms of heat (fresh, dried, fermented) for complexity.

- Use oil as a carrier to distribute capsaicin evenly.

- Prepare and store bases in advance for consistency and efficiency.

- Respect regional traditions while adapting to personal taste.

Mastering the spicy flavor profile of bases transforms cooking from reactive to strategic. Whether crafting a simple tomato sauce or an elaborate curry, the foundation determines the outcome. Heat, when built with intention, becomes not a sensation but a story—one that unfolds with every bite.

Experiment this week: Make a double batch of a spicy base (e.g., red curry paste or berbere blend). Use one immediately, freeze the other. Notice how the pre-made version saves time and deepens flavor in future meals. Share your results with #SpicyBaseChallenge.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?