Brown is one of the most versatile yet misunderstood colors in the artist’s palette. Often dismissed as a simple blend of primary colors, achieving rich, nuanced browns requires an understanding of color theory, pigment behavior, and subtle tonal variation. Whether you're working in acrylics, oils, watercolors, or digital media, mastering brown expands your ability to render earth tones, skin complexions, wood textures, and natural landscapes with authenticity and depth.

This guide breaks down the science and artistry behind creating brown, offering actionable methods, common pitfalls to avoid, and professional insights that elevate your mixing skills from basic to refined.

Understanding How Brown Is Formed

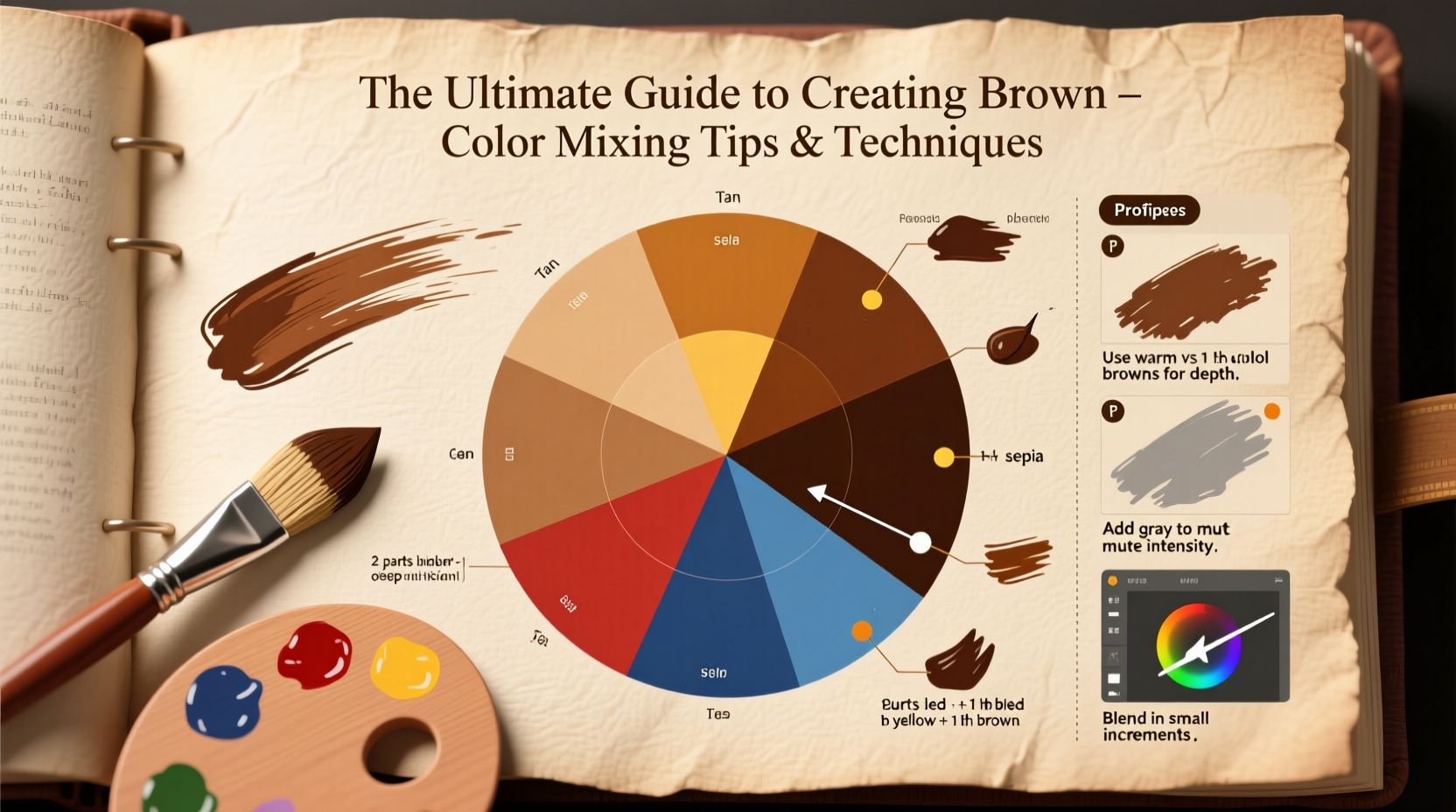

Brown is not a spectral color like red or blue—it doesn’t appear on the traditional color wheel. Instead, it emerges when complementary colors (opposites on the color wheel) are mixed, or when all three primary colors combine in varying proportions. The resulting hue depends heavily on the intensity, transparency, and undertones of the pigments used.

For example, combining cadmium red and viridian green produces a warm olive-brown, while ultramarine blue and burnt sienna yield a deep, cool chocolate tone. The key is balance: too much of one color skews the mix toward that dominant hue rather than a true neutral brown.

“Brown isn’t the absence of color—it’s the harmony of opposing forces. When you understand how complements cancel each other out, you gain control over shadow, warmth, and realism.” — Julian Hart, Muralist & Color Theory Instructor

Core Methods for Mixing Brown

There are several reliable approaches to generate brown, each suited to different artistic needs. Experimentation is essential, but starting with proven formulas accelerates learning and consistency.

Mixing Complementary Colors

Pairing opposites on the color wheel neutralizes their vibrancy and creates muted tones, often leaning into brown territory:

- Red + Green = Warm terracotta or rusty brown

- Orange + Blue = Rich chocolate or walnut

- Yellow + Purple = Earthy mustard or umber-like shade

Combining All Three Primaries

Equal parts red, yellow, and blue create a neutral gray-brown. Adjusting ratios shifts the temperature:

- More red/yellow → warmer, reddish-brown

- More blue → cooler, ashy brown

Using Pre-Made Earth Tones

Pigments like Burnt Sienna, Raw Umber, and Van Dyke Brown are naturally occurring browns derived from iron oxides. These offer consistency and depth without complex mixing. However, relying solely on tube colors limits flexibility. Use them as anchors, then modify with other hues to achieve custom variations.

Step-by-Step Guide to Creating Custom Browns

Follow this sequence to develop tailored brown shades for specific applications:

- Identify the purpose: Determine whether you need a warm wood tone, a cool shadow, or a skin-neutral base.

- Select base pigments: Choose two complementary colors or a primary trio based on desired warmth.

- Mix in small increments: Add the secondary/cool color gradually to avoid overpowering the mixture.

- Adjust value with white or black: Use ivory black or ultramarine for darkening; titanium white for tints (beige, tan).

- Test on scrap surface: Observe how the color dries (especially in watercolor or oil), as values shift upon drying.

- Record your formula: Note ratios and brands used for future replication.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced artists struggle with muddy results when mixing browns. Here’s what typically goes wrong—and how to fix it.

| Issue | Why It Happens | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Muddy, lifeless brown | Overmixing or using low-quality pigments with poor tinting strength | Limit palette to 2–3 high-quality pigments; mix less, blend gently |

| Too gray or dull | Excessive complementary contrast without warming bias | Add a touch of cadmium yellow or light red to revive warmth |

| Unexpected green/blue cast | Blue or green pigment dominance due to strong tinting power | Dilute with medium first, then add warm color drop by drop |

| Inconsistent batch matching | No record of previous mix; pigment settling in tubes | Label mixes; stir paints thoroughly before use |

Practical Tips for Realistic Results

Mini Case Study: Painting a Forest Floor

An environmental illustrator needed to depict a moist woodland floor under morning light. Initial attempts resulted in flat, monotonous browns. By applying layered glazing—first a base of burnt sienna and ultramarine, followed by thin washes of yellow ochre and quinacridone gold—the artist achieved depth and luminosity. Small accents of phthalocyanine green added mossy highlights, breaking up uniformity. The final result felt alive, textured, and seasonally accurate.

Essential Checklist for Confident Brown Mixing

Before beginning any project requiring brown tones, run through this checklist:

- ☑ Assess the required warmth or coolness of the brown

- ☑ Choose high-integrity pigments (avoid student-grade if precision matters)

- ☑ Prepare a mixing palette with ample space for test swatches

- ☑ Keep a journal of successful combinations (include brand names)

- ☑ Use a medium to extend drying time in oils or improve flow in acrylics

- ☑ Clean brushes thoroughly between mixes to prevent contamination

- ☑ Test dried samples—some browns darken significantly after 24 hours

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I make brown without black paint?

Absolutely. Black is not necessary. True brown arises naturally from mixing complements or primaries. Many professionals avoid black entirely, preferring to darken colors with deep complements (e.g., alizarin crimson + phthalo green for a near-black brown).

Why does my mixed brown look fake or plastic?

This usually occurs when synthetic, overly saturated pigments are combined without sufficient neutralization. Try switching to earth tones like yellow ochre, burnt umber, or Indian red, which have inherent subtlety and granulation.

How do I make beige or light brown?

Begin with a balanced brown mix, then gradually add titanium white. For creamier tones, include a minute amount of cadmium yellow or light red. Avoid adding white first—this dilutes pigment strength and leads to chalkiness.

Conclusion: Master Brown, Master Your Palette

Brown may seem unremarkable at first glance, but its role in visual storytelling is foundational. From grounding compositions to conveying age, texture, and emotion, skillfully mixed browns separate competent work from exceptional art. By understanding the principles of color interaction, avoiding common traps, and practicing intentional mixing, you transform brown from a fallback option into a powerful expressive tool.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?