The United States presidential election process is unlike that of most other democracies. Rather than being decided by a simple majority of the popular vote, the president is elected through the Electoral College system. This often leads to confusion: How many votes does a candidate actually need to win? Why do some states seem more influential than others? And what happens if no one reaches the threshold? This guide breaks down the mechanics of the U.S. electoral system with clarity and precision.

How the Electoral College Works

The U.S. Constitution established the Electoral College as a compromise between electing the president by Congress and by direct popular vote. Each state is allocated a number of electors equal to its total representation in Congress—its number of U.S. Representatives (based on population) plus two Senators. Washington, D.C., though not a state, is granted three electors under the 23rd Amendment.

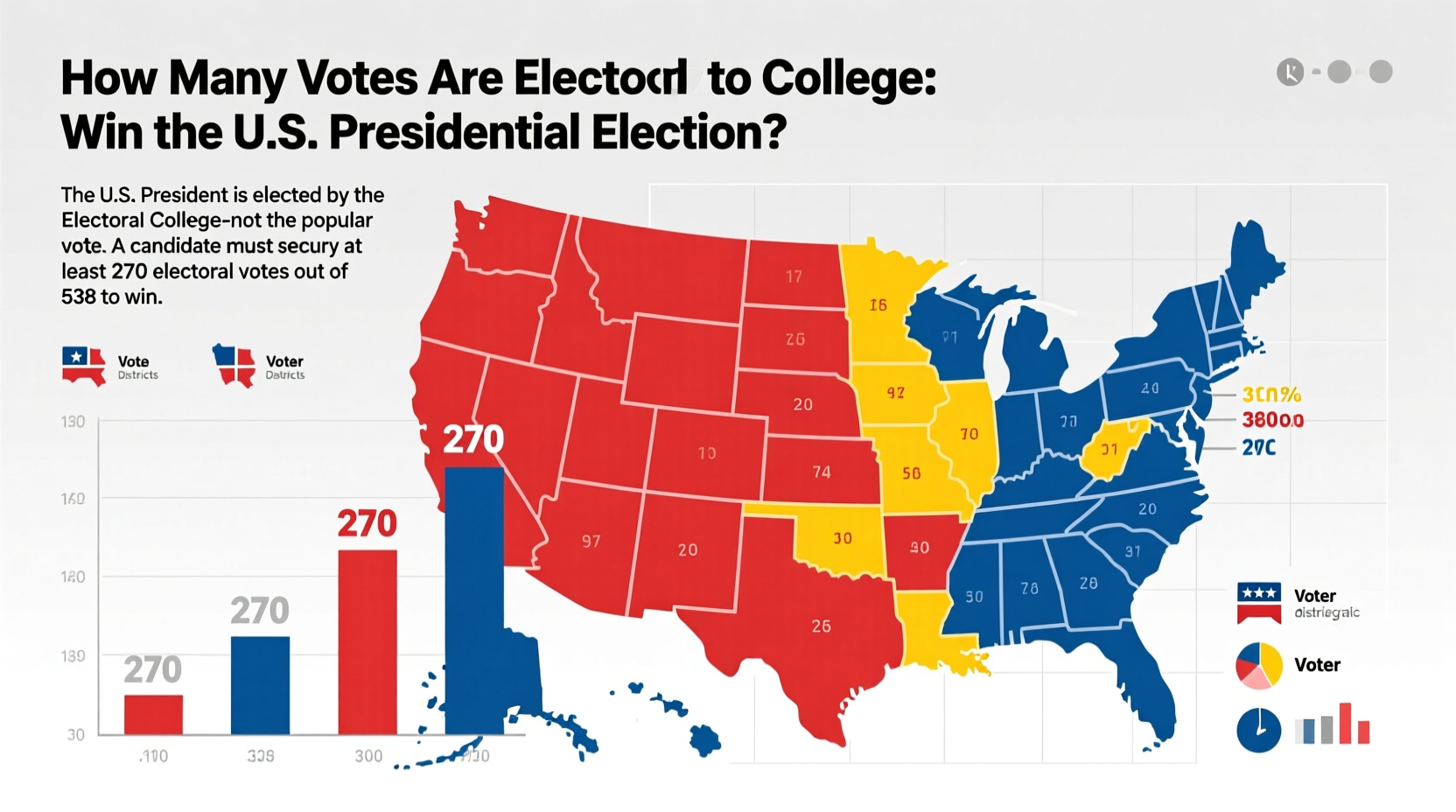

There are currently 538 electors in total. To win the presidency, a candidate must secure at least 270 electoral votes—one more than half of 538. This number is not fixed permanently; it can shift slightly after each decennial census due to reapportionment of House seats.

Electors meet in their respective states in December following the November general election to formally cast their votes. These votes are then counted in a joint session of Congress in January.

Electoral Votes by State: A Snapshot

The distribution of electoral votes reflects population disparities across states. California, the most populous state, holds 54 electoral votes as of 2024, while seven states—Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming—each have only three.

The table below shows selected states and their electoral vote counts based on the 2020 census data (effective through 2030):

| State | Electoral Votes | Population (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|

| California | 54 | 39 million |

| Texas | 40 | 30 million |

| Florida | 30 | 22 million |

| New York | 28 | 20 million |

| Illinois | 19 | 12.7 million |

| Pennsylvania | 19 | 13 million |

| Ohio | 17 | 11.8 million |

| Wyoming | 3 | 580,000 |

This imbalance means that voters in less populous states have slightly more influence per capita in the Electoral College than those in larger states.

Winning Strategies: Paths to 270 Electoral Votes

Candidates don’t need to win every state—only enough to surpass the 270 threshold. Campaigns focus heavily on “swing states” or “battleground states,” where the outcome is uncertain and can tip the balance. Examples include Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, Wisconsin, Arizona, and Nevada.

A winning campaign typically combines strong support in reliably partisan states (e.g., Democrats in California, Republicans in Alabama) with narrow victories in competitive ones. For instance, winning California (54), Texas (40), Florida (30), and New York (28) would already total 152 votes—less than halfway. The remaining 118 must come from a mix of smaller and swing states.

“Presidential candidates don’t campaign nationally—they campaign in a handful of pivotal states where margins matter most.” — Dr. Rebecca Thomas, Political Science Professor at Georgetown University

What Happens If No Candidate Reaches 270?

If no candidate secures 270 electoral votes, the election is decided by the U.S. House of Representatives under a process known as a “contingent election.” This has happened only a few times in history, most recently in 1824.

In this scenario:

- The House selects the president from among the top three electoral vote-getters.

- Each state delegation casts one vote, regardless of size. A majority of states (26 out of 50) is required to win.

- The Senate independently elects the vice president from the top two vice-presidential candidates, with each senator casting one vote.

This process underscores the constitutional weight given to states rather than individual voters in such rare outcomes.

Common Misconceptions About Winning the Presidency

Several myths persist about how presidents are elected:

- Myth: The candidate with the most popular votes automatically wins.

Reality: The winner is determined by electoral votes. In 2000 and 2016, the winner lost the popular vote but secured 270+ electoral votes. - Myth: Every vote counts equally nationwide.

Reality: Due to the Electoral College and state-based allocation, a vote in Wyoming carries more electoral weight than one in California. - Myth: Electors are legally bound to follow their state’s popular vote.

Reality: While 33 states and D.C. have laws binding electors, “faithless electors” have occasionally voted for someone other than the winner of their state. However, recent Supreme Court rulings have upheld state enforcement of these laws.

Step-by-Step: How the Election Unfolds After November

- November – General Election Day: Voters cast ballots for president, effectively choosing their state’s electors.

- Late November – Certification: States certify their results and finalize the list of electors.

- December – Electoral Vote Casting: Electors meet in their states and send certified results to Congress.

- January 6 – Congressional Count: Congress meets in joint session to count electoral votes and officially declare the winner.

- January 20 – Inauguration Day: The president-elect is sworn into office.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a candidate win with less than 270 electoral votes?

No. A candidate must receive at least 270 electoral votes to win outright. If no one reaches 270, the House of Representatives chooses the president from the top three candidates.

Why is 270 the magic number?

Because there are 538 total electoral votes, a majority requires 270. It’s one more than half of 538 (which is 269).

Do all of a state’s electoral votes go to one candidate?

In 48 states and D.C., yes—this is the “winner-takes-all” system. Maine and Nebraska use the “Congressional District Method,” awarding one electoral vote per district and two based on statewide results.

Action Checklist for Understanding the Electoral Process

- ✅ Learn your state’s number of electoral votes

- ✅ Understand whether your state uses winner-takes-all or district-based allocation

- ✅ Identify key swing states that often decide elections

- ✅ Follow certification deadlines and the December elector meeting date

- ✅ Watch the January 6 congressional count to see the official result confirmed

Real Example: The 2000 Election and the Path to 270

The 2000 presidential race between George W. Bush and Al Gore illustrates how critical a single state can be. Gore won the national popular vote by over 500,000 ballots but fell short in the Electoral College. The outcome hinged on Florida’s 25 electoral votes.

After a controversial recount and legal battle that reached the U.S. Supreme Court (*Bush v. Gore*), Florida was awarded to Bush by a margin of just 537 votes. That gave him exactly 271 electoral votes—just one over the required 270. Without Florida, he would have had only 246.

This case highlights how a razor-thin margin in one state can determine the presidency, even when the national popular vote favors the opponent.

Conclusion

Winning the U.S. presidential election requires precisely 270 electoral votes—a majority of the 538 available. While millions of Americans cast ballots in November, the outcome is determined by a complex state-based system that emphasizes geographic balance over pure population totals. Understanding this process empowers voters to appreciate not just who wins, but how and why.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?