The bright tang of a ripe tomato is one of the most defining flavors in global cuisine. Whether simmered into a rich Italian ragù, blended into a Mexican salsa, or sliced fresh over bruschetta, tomatoes deliver a complex interplay of sweetness and acidity that shapes entire dishes. Yet, for all their culinary ubiquity, the acidity level of tomatoes remains poorly understood by many home cooks—leading to overly sharp sauces, unbalanced dressings, or digestive discomfort for sensitive individuals. Understanding tomato acidity isn’t just about pH numbers; it’s about mastering flavor equilibrium, texture development, and ingredient compatibility in everyday cooking.

Acidity in tomatoes is not a flaw—it’s a feature. It acts as a natural preservative, enhances aroma, and lifts other ingredients from flatness to brilliance. But when unchecked, high acidity can dominate a dish or react unpredictably with cookware, dairy, or baking agents. This article provides a comprehensive, science-backed exploration of tomato acidity: what influences it, how it varies across types and preparations, and—most importantly—how to manage it effectively in real-world recipes.

Definition & Overview

Tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum) are botanically classified as berries and culinarily treated as vegetables. Native to western South America, they were introduced to Europe in the 16th century and have since become foundational in Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, Latin American, and Asian cuisines. While commonly associated with red color and juicy flesh, tomatoes vary widely in size, shape, color (yellow, orange, purple, green, striped), and chemical composition.

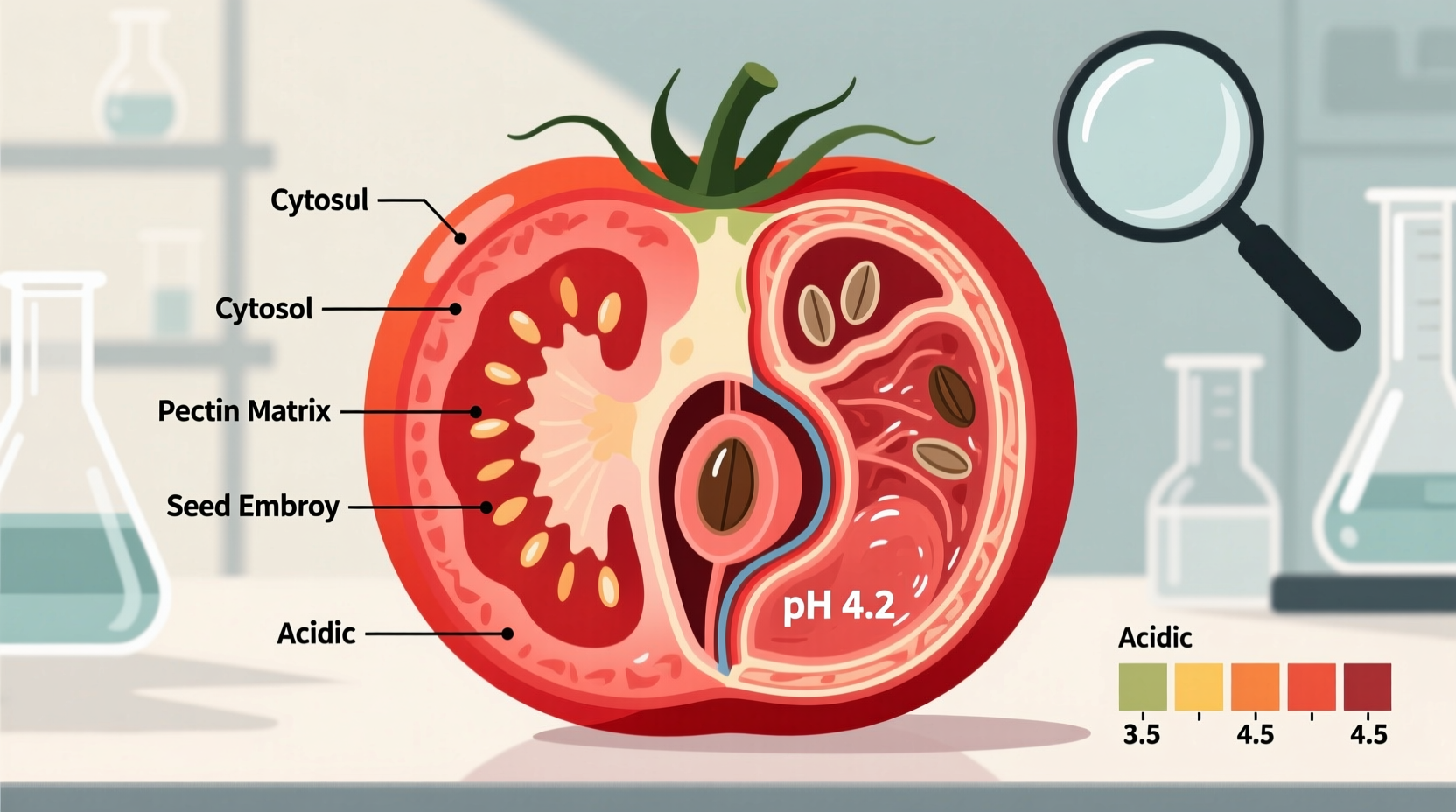

One of the most influential chemical properties of tomatoes is their acidity, primarily due to citric and malic acids. These organic acids contribute significantly to taste perception, microbial stability, and interaction with other ingredients during cooking. The pH of most ripe tomatoes ranges between 4.3 and 4.9, placing them firmly in the acidic category (pH below 7). For reference, lemon juice has a pH of around 2.0–2.6, while milk is near neutral at 6.5–6.7. Despite being less acidic than citrus, tomatoes are still potent enough to influence digestion, flavor layering, and even food safety practices like home canning.

Key Characteristics of Tomato Acidity

- pH Range: 4.3–4.9 (ripe), dropping slightly in underripe fruit

- Primary Acids: Citric acid (~60%), malic acid (~30%), with traces of ascorbic (vitamin C) and oxalic acid

- Flavor Impact: Bright, tart, mouthwatering; balances sweetness and umami

- Aroma Influence: Volatile compounds responsible for “fresh tomato” scent are more volatile at lower pH, enhancing perceived freshness

- Culinary Function: Acts as a flavor enhancer, tenderizer (in marinades), and preservative (in pickling and canning)

- Shelf Life: Higher acidity inhibits bacterial growth but accelerates enzymatic browning when cut

- Digestive Consideration: May trigger heartburn or GERD symptoms in sensitive individuals

Pro Tip: Acid-sensitive tasters often confuse sourness with bitterness. True tomato acidity is clean and fruity—not harsh or metallic. If your tomatoes taste unpleasantly sharp, they may be underripe or stored improperly.

Factors That Influence Tomato Acidity

Not all tomatoes are equally acidic. Multiple variables affect their pH and perceived tartness:

Variety (Cultivar)

Some cultivars are naturally lower in acid. Yellow and orange heirlooms such as ‘Golden Sunray’ or ‘Persimmon’ tend to have higher sugar-to-acid ratios, resulting in milder, sweeter profiles. In contrast, classic red varieties like ‘Roma’ or ‘San Marzano’ maintain a sharper bite ideal for long-cooked sauces.

Ripeness

As tomatoes ripen, acid levels decrease while sugars increase. A fully vine-ripened tomato will taste rounder and more balanced than one picked green and gassed for color. However, if left too long, degradation of acids can lead to flat, insipid flavor.

Growing Conditions

Sun exposure, soil composition, irrigation, and temperature all impact acid development. Tomatoes grown in cooler climates often retain higher acidity. Calcium-rich soils can buffer acidity slightly and improve cell wall integrity, reducing mushiness during cooking.

Post-Harvest Handling

Refrigeration slows ripening but can dull flavor and intensify perceived acidity by suppressing aromatic volatiles. Store ripe tomatoes at room temperature, stem-side down, for optimal flavor expression.

Practical Usage: Managing Acidity in Cooking

Knowing how to modulate tomato acidity separates competent cooks from skilled ones. The goal is rarely elimination—but rather balance.

Neutralizing Excess Acidity

If a sauce or soup tastes too sharp, do not reach for sugar first. Instead, consider these professional techniques:

- Add Fat: A swirl of olive oil or butter coats the palate and softens acidic perception. Emulsified fats, like those in a finished Béarnaise or aioli, are especially effective.

- Incorporate Umami-Rich Ingredients: Anchovies, Parmesan rind, soy sauce, or dried mushrooms deepen savoriness without adding sweetness, counterbalancing acidity through complexity rather than masking.

- Use Starchy Thickeners: A teaspoon of cornstarch slurry or a mashed potato knob thickens and rounds out texture, which indirectly tempers acidity.

- Simmer with Aromatics: Onion, carrot, and celery (mirepoix) caramelize slowly, releasing natural sugars that harmonize with acid over time.

- Introduce Alkaline Agents Sparingly: Baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) chemically neutralizes acid. Use no more than ⅛ teaspoon per quart of sauce to avoid soapy off-flavors or loss of structure.

Preserving Desired Acidity

In raw applications—gazpacho, pico de gallo, vinaigrettes—acidity is essential. To preserve it:

- Use freshly cut tomatoes within 30 minutes of preparation to maximize volatile aroma retention.

- Add salt early: sodium ions suppress bitter notes and enhance both sweet and sour perception.

- Pair with creamy elements like avocado or feta to create textural contrast that highlights brightness.

Canning and Preservation Safety

Because tomatoes hover near the threshold of safe acidity for water-bath canning (pH 4.6 is the cutoff for preventing Clostridium botulinum growth), USDA guidelines require acidification when processing low-acid types:

| Type of Tomato Product | Required Acid Addition | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Whole/Chunked Tomatoes (pH > 4.6) | 1 tbsp bottled lemon juice or ¼ tsp citric acid per pint | Ensure safe pH ≤ 4.3 |

| Tomato Juice | 1 tbsp lemon juice per quart | Prevent pathogen risk |

| Tomato Sauce with Onions/Peppers | Double acid addition recommended | Vegetable dilution lowers overall acidity |

\"When preserving tomatoes, never assume visual ripeness equals safe acidity. Always test with pH strips if experimenting with heirloom varieties, and always follow tested recipes from trusted sources like the National Center for Home Food Preservation.\" — Dr. Linda Harris, Food Microbiologist, UC Davis

Variants & Types: How Form Affects Acidity

The form in which tomatoes are used dramatically alters their acid concentration and behavior in cooking.

| Type | Average pH | Acidity Notes | Best Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh Ripe Tomato | 4.3–4.9 | Balanced citric/malic profile; volatile aromas peak at room temp | Salsas, salads, sandwiches, quick sautés |

| Canned Whole/Stewed | 4.0–4.6 | Slight acid drop due to heat processing; may include added citric acid for preservation | Stews, curries, braises, pantry sauces |

| Tomato Paste | 5.8–6.4 (concentrated solids) | Lower pH initially, but Maillard reaction during concentration creates deeper, less tart flavor | Flavor base for sauces, soups, rubs |

| Sun-Dried Tomatoes (oil-packed) | 4.0–4.5 | Higher perceived acidity due to water removal concentrating acids | Pasta, tapenade, grain bowls, antipasto |

| Dehydrated Powder | ~4.2 | Intense umami with residual tartness; dissolves easily in liquids | Seasoning blends, dry rubs, instant soups |

Note: Tomato paste, despite its deep color and richness, is actually less acidic in functional terms because prolonged heating breaks down some organic acids and promotes caramelization. Its role is more about depth than brightness.

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Tomato acidity is often compared—or substituted—for other souring agents. Here's how they differ:

| Ingredient | pH | Primary Acid | Flavor Profile | Substitution Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato (fresh) | 4.3–4.9 | Citric, Malic | Fruity, vegetal, rounded | N/A – baseline |

| Lemon Juice | 2.0–2.6 | Citric | Sharp, clean, piercing | Use ¼ volume of lemon juice to match tomato tartness; add sweetness separately |

| Vinegar (white) | 2.4–3.4 | Acetic | Pungent, sharp, fermented | Not interchangeable; acetic acid lacks fruitiness and reacts differently in emulsions |

| Pomegranate Molasses | 4.0–4.5 | Tartaric, Citric | Fruity, wine-like, slightly tannic | Can replace tomato concentrate in Middle Eastern dishes; darker color, more viscosity |

| Green Mango (shredded) | 3.4–4.0 | Malic, Ascorbic | Crisp, tropical, fibrous | Good substitute in Southeast Asian salads where texture matters more than juiciness |

Crucially, no other ingredient replicates the full-spectrum contribution of tomatoes: their combination of moisture, acidity, umami (from glutamates), and aroma is irreplaceable in dishes like ragù, shakshuka, or chermoula.

Practical Tips & FAQs

Does cooking reduce tomato acidity?

Not significantly in pH terms. While prolonged simmering can slightly lower measured acidity through evaporation and Maillard reactions, the change is minimal. What shifts is perception: caramelized sugars, fat integration, and aromatic development make the final dish taste less sharp even if pH remains stable.

Are \"low-acid\" tomatoes safe for canning?

No variety is reliably low-acid enough for safe water-bath canning without added acid. Even yellow tomatoes marketed as “gentle” can exceed pH 4.6. Always follow current USDA guidelines and acidify unless using a pressure canner.

Can I substitute fresh tomatoes for canned in recipes?

Yes, but adjust for water content. One pound of fresh tomatoes (peeled, seeded, drained) ≈ 1 cup canned crushed tomatoes. Simmer fresh purée for 15–20 minutes to concentrate flavor before use.

Why does my tomato sauce taste metallic?

This often results from cooking acidic foods in reactive pans (aluminum, unlined copper). Switch to stainless steel, enamel-coated cast iron, or glass. Also check for expired canned tomatoes—older cans may leach trace metals.

How can I grow less acidic tomatoes?

Choose known low-titratable-acid cultivars like ‘Arkansas Traveler’, ‘Cherokee Purple’, or ‘Great White’. Grow in warm, sunny conditions with consistent watering and adequate potassium, which supports sugar production.

Is tomato acidity harmful to health?

For most people, no. The acids in tomatoes are metabolized normally and contribute to antioxidant intake (e.g., vitamin C). However, individuals with acid reflux, IBS, or kidney stones (due to oxalates) may need to moderate intake. Cooking reduces irritants slightly compared to raw consumption.

Quick Checklist: Balancing Tomato Acidity in Sauces

- Start with quality, ripe tomatoes

- Sauté aromatics (onion, garlic) until golden to build sweetness

- Add tomatoes gradually, allowing evaporation between additions

- Taste after 20 minutes of simmering—adjust only then

- Finish with fat (olive oil, butter) and umami boosters (Parmesan rind, anchovy)

- Resist sugar unless absolutely necessary; use grated carrot or roasted pepper instead

Summary & Key Takeaways

Tomato acidity is a dynamic, multifaceted property that defines much of their culinary value. Far from a single metric, it encompasses pH, flavor balance, chemical interactions, and sensory perception. Understanding it empowers cooks to craft better dishes, preserve safely, and accommodate diverse palates.

Key points to remember:

- Tomatoes are mildly acidic (pH 4.3–4.9), primarily due to citric and malic acids.

- Acidity enhances flavor, preserves food, and interacts critically with cookware and other ingredients.

- Ripeness, variety, and growing conditions significantly influence acid levels.

- In cooking, balance acidity with fat, umami, starch, or minimal alkaline agents—not just sugar.

- All tomato products intended for water-bath canning must meet minimum acidity standards, often requiring added lemon juice or citric acid.

- No substitute fully replicates the integrated acidity, moisture, and umami of real tomatoes.

Mastering tomato acidity means moving beyond instinctual adjustments toward intentional, informed seasoning. Whether crafting a delicate summer salad or a robust winter stew, recognizing the role of acidity allows for greater control, consistency, and confidence in the kitchen.

Next time you prepare a tomato-based dish, conduct a simple experiment: prepare two batches—one with a pinch of baking soda, one without. Taste them side by side. Notice not just the reduction in tartness, but the subtle flattening of aroma and depth. That moment of comparison is the beginning of true flavor literacy.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?