Water is one of the most abundant and essential substances on Earth, yet it behaves in ways that defy typical physical expectations. One of the most fascinating anomalies is its density change when transitioning from liquid to solid form. Unlike most materials, which become denser as they cool and solidify, water reaches its maximum density at 4°C and becomes less dense when it freezes into ice. This seemingly small quirk has profound implications for life on Earth, from aquatic ecosystems to climate systems. Understanding the density differences between water and ice reveals not only fundamental principles of chemistry and physics but also highlights nature’s delicate balance.

The Basics of Density and Phase Changes

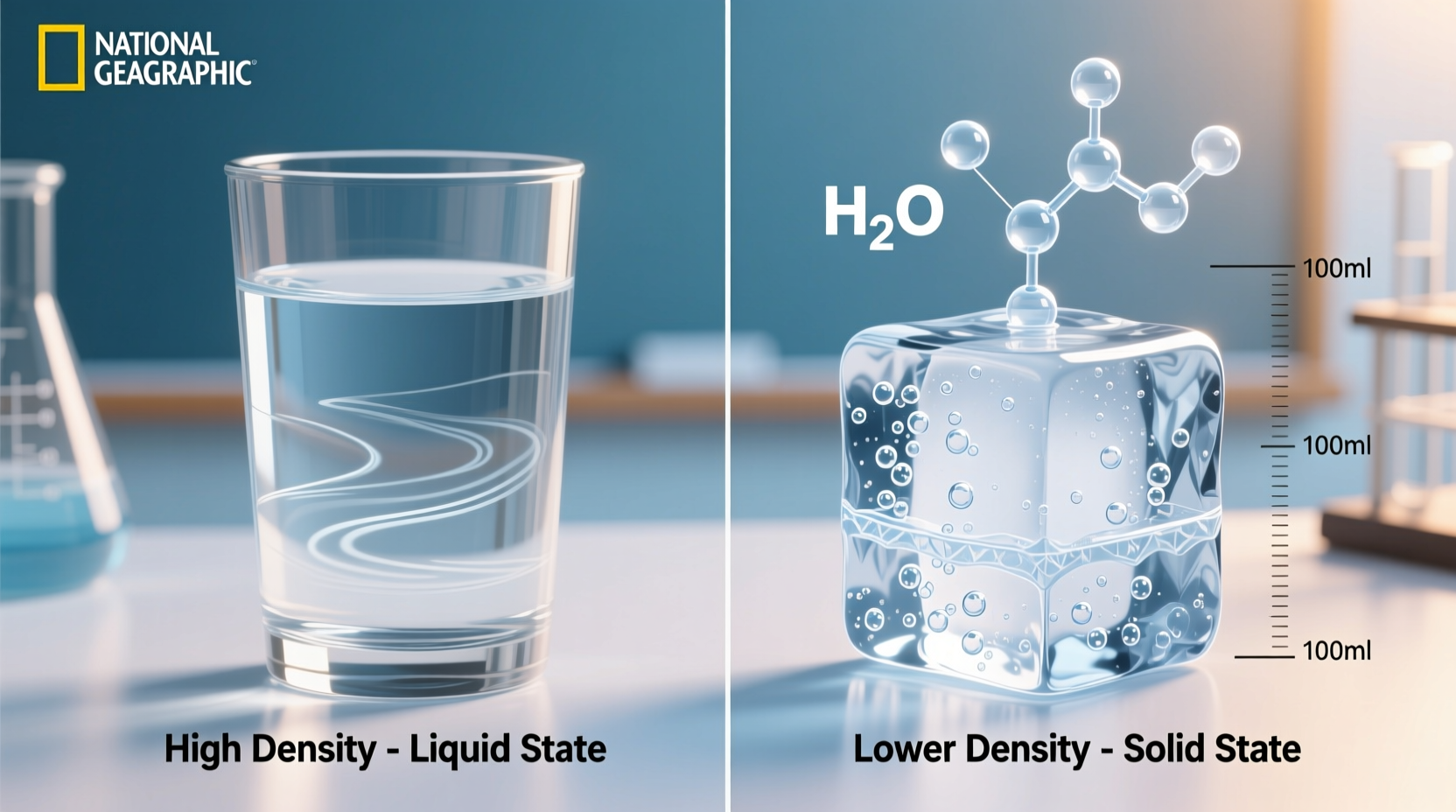

Density is defined as mass per unit volume (ρ = m/V). When a substance cools, its molecules typically move more slowly and pack closer together, increasing density. For most liquids, solidification results in a more compact molecular arrangement. Water follows this trend down to 4°C, where it reaches its highest density—approximately 1.000 g/cm³. However, as it continues to cool toward 0°C and freezes, something unusual happens: the molecules begin forming a hexagonal crystalline lattice due to hydrogen bonding, creating more space between them. This expansion causes ice to be about 9% less dense than liquid water, allowing it to float.

This property is rare in nature. Most substances, such as carbon dioxide or ethanol, have solids that sink in their own liquids. But water’s ability to expand upon freezing makes it an exception—and a critical one for planetary habitability.

Molecular Behavior: Why Ice Is Less Dense

The secret lies in water’s molecular structure. A water molecule consists of two hydrogen atoms bonded to one oxygen atom (H₂O), forming a bent shape with a partial positive charge on the hydrogens and a partial negative charge on the oxygen. This polarity enables hydrogen bonds—weak electrostatic attractions between the hydrogen of one molecule and the oxygen of another.

In liquid water, these bonds are constantly forming and breaking, allowing molecules to remain relatively close. As temperature drops, molecular motion slows, and hydrogen bonds stabilize. At 0°C, during freezing, each water molecule forms four hydrogen bonds in a tetrahedral configuration, locking into a rigid, open hexagonal lattice. This structure contains large empty spaces compared to the more randomly packed but tighter arrangement in liquid water.

The increased volume without added mass means lower density. Thus, ice occupies more space than the same mass of liquid water, making it buoyant.

“Water’s density anomaly is not just a curiosity—it’s a cornerstone of Earth’s biosphere.” — Dr. Alan Pierce, Physical Chemist, MIT

Real-World Implications: How Floating Ice Supports Life

If ice were denser than water, it would sink as it formed. In lakes and oceans, this would lead to continuous freezing from the bottom up, potentially turning entire bodies of water into solid ice over time. But because ice floats, it forms an insulating layer on the surface, slowing further heat loss and protecting aquatic life below.

A realistic example illustrates this: consider a northern lake in winter. As air temperatures drop, surface water cools, becomes denser, and sinks until the entire water column reaches 4°C. Further cooling makes surface water less dense, so it stays on top. Once it hits 0°C, ice begins to form. This floating ice sheet reduces convection and limits additional freezing, maintaining a liquid environment beneath where fish, plants, and microorganisms survive.

This phenomenon also influences global climate patterns. Sea ice reflects sunlight (high albedo), helping regulate Earth’s temperature. Its formation and melting affect ocean salinity and currents, playing a role in thermohaline circulation—the “global conveyor belt” that redistributes heat around the planet.

Practical Applications and Common Misconceptions

Understanding water’s density behavior helps explain everyday occurrences and prevent damage. For instance, homeowners are often warned to drain outdoor pipes in winter. When water freezes inside a pipe, its expansion can exert pressures exceeding 2,000 psi, enough to crack metal or burst PVC.

Another common misconception is that all frozen water is the same. In reality, different types of ice—such as hexagonal ice (Ih), found naturally on Earth, versus cubic ice (Ic) formed under specific lab conditions—have slightly different densities and structures. Only Ih exhibits the familiar low-density lattice that allows floating.

| State of Water | Temperature | Density (g/cm³) | Molecular Arrangement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Water | 4°C | 1.000 | Random, closely packed |

| Liquid Water | 0°C | 0.99987 | Slightly expanded |

| Ice (solid) | 0°C | 0.9167 | Hexagonal lattice, open structure |

Step-by-Step: Observing Density Differences at Home

You can demonstrate this principle with simple household items:

- Gather a clear glass, water, and a few ice cubes.

- Fill the glass nearly full with water.

- Gently place an ice cube into the glass.

- Observe how the ice floats, displacing some water.

- Mark the water level and wait for the ice to melt completely.

- Note that the water level remains unchanged after melting.

This shows that the mass of the ice equals the mass of the water it displaces—confirming Archimedes’ principle and illustrating that melting floating ice does not raise sea levels (though land-based glacial melt does).

Frequently Asked Questions

Why doesn’t ice sink if it’s colder than water?

Although colder, ice has a more open molecular structure due to hydrogen bonding. This increases volume and decreases density, overriding the usual expectation that colder = denser.

Does saltwater behave the same way?

Saltwater also forms ice that floats, but its freezing point is lower (around -2°C depending on salinity), and the expelled salt creates brine channels in sea ice. The density dynamics are similar but modified by dissolved ions.

Can water freeze without expanding?

Under high pressure, water can form denser ice phases like ice II, III, or IX, which are actually denser than liquid water. But these do not occur under normal atmospheric conditions.

Conclusion: Embracing the Anomaly

The fact that ice floats may seem trivial, but it underpins much of Earth’s environmental stability. From preserving underwater habitats to moderating climate extremes, water’s inverse density relationship is a quiet guardian of life. Recognizing this scientific marvel deepens appreciation for the natural world and underscores the importance of accurate scientific literacy. Whether you're a student, educator, or simply curious, take a moment to observe a glass of ice water—not just as a refreshment, but as a window into one of nature’s most vital exceptions.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?