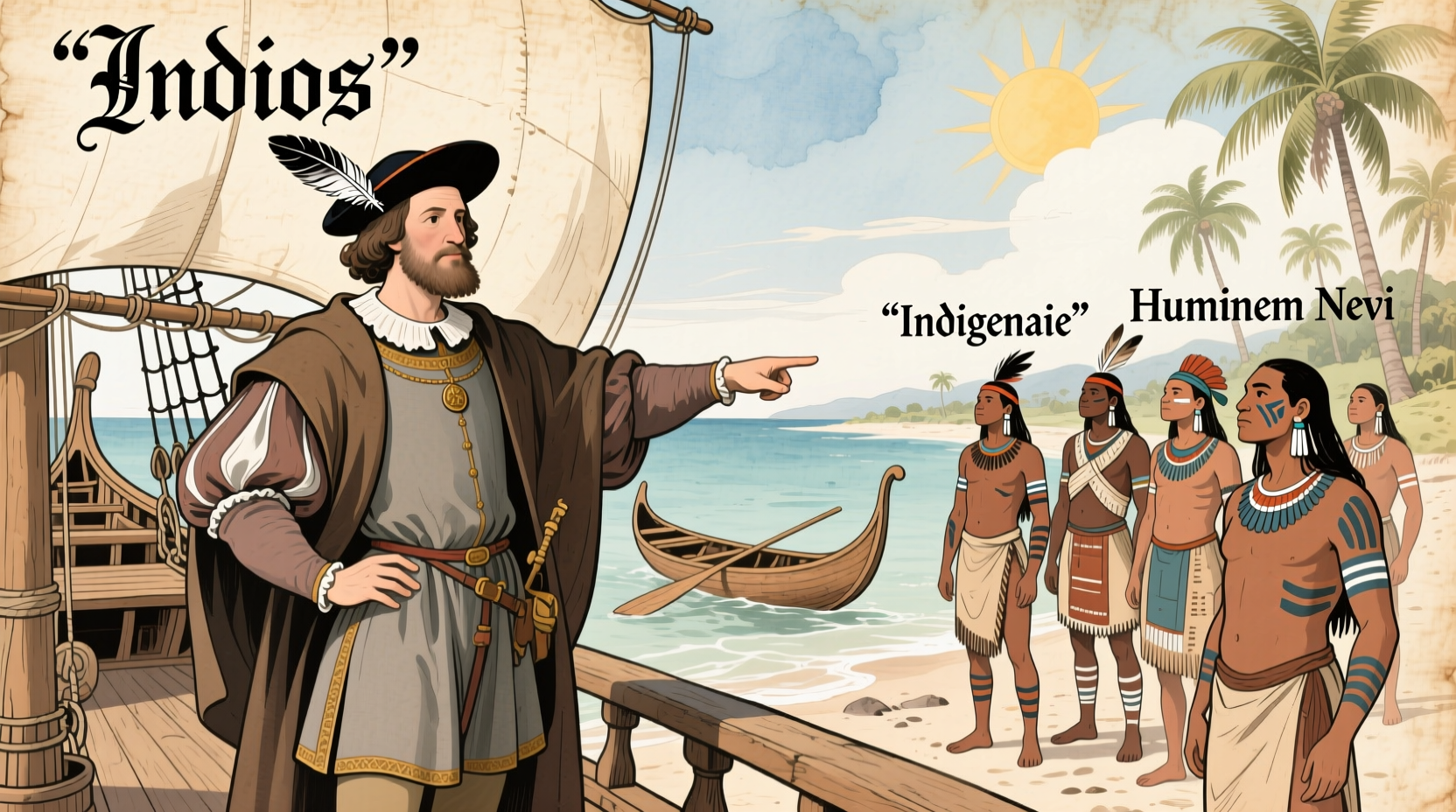

When Christopher Columbus first landed in the Caribbean in 1492, he encountered people whose cultures, languages, and histories were entirely unknown to him. In his writings, Columbus referred to these Indigenous inhabitants using terms that reflected his geographical misconceptions and cultural biases. The labels he applied not only misrepresented the people he met but also laid the foundation for centuries of misnaming and marginalization. Understanding what Columbus called Native peoples, where those terms originated, and how they evolved over time is essential to grasping the broader legacy of European colonization in the Americas.

Columbus’s First Encounters and Initial Terminology

Upon arriving in the Bahamas, Columbus believed he had reached the outer edges of Asia—specifically the Indies, a term Europeans used broadly for South and Southeast Asia. As a result, he referred to the Indigenous people he encountered as los Indios, or “Indians.” This misnomer stemmed directly from his mistaken belief that he had sailed westward to reach India. Despite later explorers realizing the geographic error, the term \"Indian\" persisted across Europe and its colonies for hundreds of years.

In his journal entries and letters, Columbus described the Taíno people of the Greater Antilles with terms like “gentle,” “timid,” and “naked,” emphasizing their physical appearance and perceived lack of European customs. He also noted their generosity and willingness to trade, which he interpreted as a sign of naivety rather than diplomacy. These early descriptions set a precedent for dehumanizing portrayals of Native Americans in European narratives.

The Origin and Spread of the Term “Indian”

The word “Indian” entered European lexicons through Columbus’s reports to the Spanish Crown. Since he was under the impression that he had reached the Indian Ocean region, it was natural for him to assume the inhabitants were “Indios.” This label was quickly adopted by other explorers, cartographers, and chroniclers throughout the 15th and 16th centuries.

Even after Amerigo Vespucci and others confirmed that the lands were part of a previously unknown continent, the name stuck. The term appeared on maps, legal documents, and missionary records across Spain, Portugal, France, and England. Over time, “Indian” became a blanket designation for all Indigenous peoples of the Americas, despite the vast diversity among nations, tribes, and civilizations—from the Inuit of the Arctic to the Mapuche of southern Chile.

“Columbus didn’t discover a new world—he mislabeled one.” — Dr. Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Indigenous Scholar and Author of *Decolonizing Methodologies*

Alternative Names and Their Implications

As awareness grew about the inaccuracy of “Indian,” alternative terms emerged, each carrying its own political, cultural, and historical weight. Some of the most commonly used labels include:

- American Indian – A formal term used in U.S. government contexts, especially during the 19th and 20th centuries. Though still recognized legally, many find it outdated due to its colonial roots.

- Native American – Gained popularity in the late 20th century as a more accurate and respectful descriptor. It emphasizes indigeneity and pre-colonial presence.

- Indigenous Peoples – A global term preferred in academic and international settings (e.g., United Nations). It acknowledges sovereignty and shared experiences of colonization.

- First Nations – Used primarily in Canada to refer to status and non-status Indigenous groups excluding Inuit and Métis.

- Aboriginal – Common in Australia and sometimes used in Canada, though increasingly replaced by more specific identifiers.

Importantly, many communities prefer to be identified by their specific nation or tribal affiliation—such as Navajo, Lakota, Quechua, or Māori—rather than broad pan-ethnic terms.

Timeline of Terminology Evolution

The language used to describe Native peoples has shifted significantly since 1492. Below is a timeline highlighting key developments:

- 1492 – Columbus lands in the Bahamas and begins referring to inhabitants as “Indios.”

- 1507 – Martin Waldseemüller names the new continent “America” after Amerigo Vespucci, but “Indian” remains in use for its people.

- 1800s – “American Indian” becomes standard in U.S. policy and census records.

- 1960s–1970s – Civil rights movements prompt reevaluation of racial and ethnic labels; “Native American” gains traction.

- 1980s–Present – Academic and activist circles promote “Indigenous” as a decolonizing term.

- 2020s – Federal agencies in the U.S. and Canada increasingly adopt nation-specific naming and phase out “Indian” in official usage.

Do’s and Don’ts of Modern Terminology

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Use specific tribal or national names when known (e.g., Cherokee, Ojibwe) | Assume all Native people are the same or use generic terms without context |

| Follow community preferences—some embrace “Indian,” others reject it | Use “Indian” casually or in stereotypical phrases (“Indian giver,” “on the warpath”) |

| Use “Indigenous” in global or academic discussions | Use outdated or offensive terms like “savage,” “primitive,” or “redskin” |

| Respect self-identification and ask when unsure | Impose external labels based on tradition or convenience |

Mini Case Study: The Name Change of the Washington NFL Team

For decades, the Washington NFL team used a name widely regarded as a racial slur against Native Americans. While officially called the “Redskins” since 1933, the term had long been criticized for its derogatory connotations. Activists, tribal leaders, and scholars campaigned for change, citing psychological harm and perpetuation of stereotypes.

In 2020, amid nationwide protests for racial justice, corporate sponsors pressured the team to reevaluate its branding. The organization retired the old name and logo, eventually becoming the Washington Commanders in 2022. This shift exemplifies how public awareness of historical terminology—rooted in misrepresentation beginning with figures like Columbus—can lead to meaningful institutional change.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did Columbus call Native people “Indians”?

Columbus believed he had reached the East Indies (Asia) by sailing west. Since he thought he was in India, he referred to the local inhabitants as “Indios,” a term derived from the Spanish word for Indians. The name endured despite geographical corrections.

Is it offensive to say “Indian” today?

It depends on context and preference. Some Native individuals and communities, particularly older generations or those involved in organizations like the National Congress of American Indians, still use “Indian” due to legal recognition (e.g., “American Indian”). However, many consider it outdated or inaccurate. When in doubt, opt for “Native American,” “Indigenous,” or the person’s specific tribal affiliation.

What should I say instead of “Indian”?

Use “Native American” in U.S. contexts, “First Nations” in Canada, or “Indigenous Peoples” in international or academic discussions. Whenever possible, use the specific name of the nation or tribe (e.g., Hopi, Cree, Zapotec). Always respect individual and community preferences.

Practical Checklist for Respectful Language Use

- ✅ Learn the correct names of local Indigenous nations in your area.

- ✅ Avoid pan-Indian generalizations; recognize cultural diversity.

- ✅ Replace outdated terms in writing and speech (e.g., “squaw,” “chief” as slang).

- ✅ Support media and institutions that use accurate, self-determined terminology.

- ✅ Listen to Native voices when they speak about identity and representation.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Identity Beyond Columbus’s Labels

The terminology Columbus introduced over 500 years ago continues to echo in modern discourse, but increasing awareness is reshaping how we speak about Native peoples. Moving beyond “Indian” is not just about political correctness—it’s about accuracy, respect, and justice. By understanding the origins of these terms and choosing language that honors self-identification, we contribute to a more truthful and equitable narrative.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?