Every holiday season, millions of homes transform into luminous displays—strings of LEDs, incandescent bulbs, and animated figures blinking in synchronized cheer. But behind the glow lies an often-overlooked electrical reality: Christmas lights strain household circuits more than most people realize. Overloading isn’t just inconvenient—it’s a leading cause of seasonal residential fires. According to the U.S. Fire Administration, an average of 790 home fires per year are attributed to decorative lighting, with overloading and faulty connections cited as primary contributors. This article explains precisely what occurs when you exceed a circuit’s capacity, why common assumptions about “just one more string” are dangerously misleading, and—most importantly—how to calculate, verify, and maintain safe loads without dimming your festive spirit.

How Household Circuits Work—and Why They Have Limits

A standard North American residential circuit is typically rated for 15 or 20 amps at 120 volts. That translates to a maximum continuous load of 1,800 watts (15 A × 120 V) or 2,400 watts (20 A × 120 V). Crucially, the National Electrical Code (NEC) recommends operating circuits at no more than 80% of their rated capacity for sustained loads—a safety buffer that reduces the practical limit to 1,440 watts on a 15-amp circuit and 1,920 watts on a 20-amp circuit. This derating prevents heat buildup in wires, outlets, and breakers, all of which degrade faster under constant thermal stress.

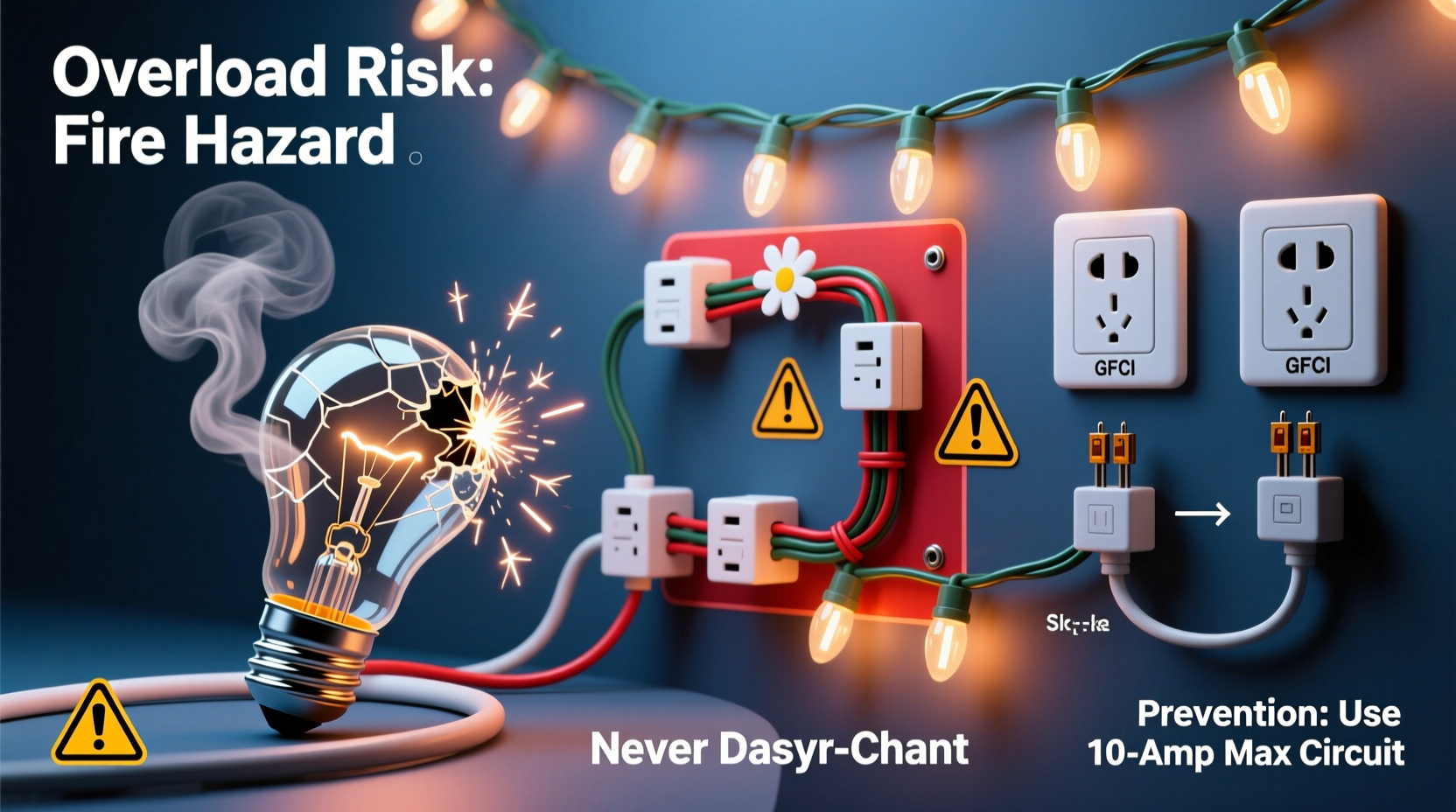

Christmas lights vary widely in power draw. Incandescent mini-lights (the classic warm-glow kind) consume roughly 0.3–0.5 watts per bulb. A 100-bulb string may draw 30–50 watts—but chain multiple strings together, and consumption escalates quickly. LED strings, by contrast, use only 4–7 watts per 100 bulbs. However, many homeowners mistakenly assume LED safety extends to unlimited daisy-chaining. While LEDs generate less heat *per string*, the outlet, extension cord, and circuit breaker still see cumulative current flow—and every connection point introduces resistance and potential failure points.

The Real Consequences of Overloading: Beyond Tripped Breakers

When a circuit exceeds its safe amperage, several interrelated physical responses occur—not all immediately obvious:

- Thermal buildup in wiring: Excess current causes conductors to heat beyond design thresholds. In older homes with aluminum wiring or degraded insulation, temperatures can exceed 90°C—enough to embrittle insulation and initiate slow pyrolysis (chemical decomposition of wire sheathing).

- Outlet and receptacle degradation: Repeated overheating loosens internal terminal screws, increases contact resistance, and creates micro-arcing. This “hot spot” effect worsens over time—even at loads below trip thresholds—until failure becomes inevitable.

- Breaker fatigue: Circuit breakers are mechanical devices. Frequent tripping accelerates wear on bimetallic strips and magnetic coils. A fatigued breaker may delay tripping—or worse, fail to trip entirely during a true fault.

- Extension cord hazards: Most seasonal overloads originate not at the circuit panel but at the outlet-to-light interface. A 16-gauge extension cord rated for 10 amps (1,200 W) becomes dangerous when feeding 1,600 watts—even if the circuit itself can handle it. Voltage drop across undersized cords further increases current draw to compensate, creating a vicious cycle.

Importantly, modern AFCI (Arc-Fault Circuit Interrupter) breakers—now required in living areas by NEC—can detect dangerous arcing before heat builds to ignition levels. But they won’t prevent thermal overload from sustained overcurrent. And they offer zero protection if the overload occurs downstream of the breaker, such as within a damaged outdoor outlet box or a coiled extension cord under mulch.

Step-by-Step: Calculate Your Safe Light Load in Under 5 Minutes

Accurate load calculation doesn’t require an electrician’s license—just attention to detail and consistent units. Follow this verified sequence:

- Identify your circuit’s rating: Locate your home’s breaker panel. Find the label for the outlet(s) powering your lights (e.g., “Living Room Outlets” or “Front Porch”). Note the amperage (15A or 20A).

- Determine your safe wattage limit: Multiply amps × 120V × 0.8. For a 15A circuit: 15 × 120 × 0.8 = 1,440 watts. For 20A: 20 × 120 × 0.8 = 1,920 watts.

- Inventory all connected devices: Don’t forget anything sharing that circuit—refrigerator compressors, entertainment centers, space heaters, or even garage door openers. Add their wattages (check nameplates or manuals; use 1,200W for refrigerators, 1,500W for heaters).

- Subtract non-light loads from your safe limit: If your 15A living room circuit already powers a TV (120W), soundbar (60W), and game console (90W), subtract 270W. Remaining capacity: 1,440 − 270 = 1,170 watts for lights only.

- Calculate light string consumption: Check each light package for wattage (not “equivalent brightness”). If unspecified, measure with a plug-in power meter ($25–$40 online)—the only truly reliable method. Avoid estimating based on bulb count alone.

This process reveals hard constraints. For example, a single 150-foot commercial-grade incandescent net light (often 240W) consumes over 20% of a fully dedicated 15A circuit’s safe capacity—before adding any other strings.

Risks in Context: A Real-World Case Study

In December 2022, a family in Portland, Oregon, decorated their two-story colonial with approximately 1,200 feet of mixed lighting: vintage incandescent C7 bulbs on the roofline, LED icicle lights along the eaves, and three animated lawn displays. All were plugged into a single outdoor GFCI outlet fed by a 15-amp circuit also powering the garage freezer and a Wi-Fi router.

On Christmas Eve, after adding a final string of 100-bulb incandescents to the front porch railing, the outlet emitted a sharp ozone smell. Within minutes, the GFCI tripped—but reset immediately when pressed. The family assumed a “momentary surge.” They reset it twice more before giving up and unplugging everything. The next morning, the outlet cover was discolored brown, and the brass terminals showed visible pitting. An electrician later measured 1,680 watts drawn at peak—16% over the NEC-recommended 1,440W limit. Thermal imaging revealed 82°C at the outlet’s hot terminal (vs. 35°C on identical outlets elsewhere). The insulation on the 12-gauge branch circuit had begun charring at the junction box where the cable entered the outlet.

No fire occurred—but the near-miss underscores how overload damage accumulates invisibly. The outlet wasn’t “blown”; it was thermally compromised, increasing future arc-fault risk exponentially. The family now uses a dedicated 20-amp circuit with a weatherproof subpanel for all exterior holiday loads.

Prevention Checklist: What to Do Before You Plug In

Use this actionable checklist before installing any lights this season:

- ✅ Map your circuits: Use a circuit breaker finder tool ($15) to identify exactly which outlets share a breaker. Label them clearly.

- ✅ Replace worn outlets: Any outlet with loose plugs, discoloration, or warmth during use must be replaced by a licensed electrician before connecting lights.

- ✅ Use outdoor-rated, heavy-gauge extension cords: For permanent or semi-permanent setups, use 12-gauge or 10-gauge cords rated for “extra heavy duty” and wet locations. Never coil active cords.

- ✅ Stagger high-wattage devices: Run animatronics, inflatable displays, and heated elements on separate circuits from static light strings.

- ✅ Install a smart plug with energy monitoring: Devices like the Emporia Vue or Kill A Watt WiFi provide real-time wattage, amperage, and cost tracking—alerting you instantly if you breach thresholds.

Do’s and Don’ts: Holiday Lighting Safety Comparison

| Action | Do | Don’t |

|---|---|---|

| Cord Management | Use cord reels designed for outdoor storage; keep cords uncoiled during operation | Run cords under rugs, through windowsills, or across high-traffic walkways |

| String Connection | Connect LED strings using manufacturer-approved connectors; verify max run length | Daisy-chain more than three incandescent strings or exceed package-specified limits |

| Outdoor Protection | Use GFCI-protected outlets; install weatherproof covers on all outdoor receptacles | Plug indoor-rated lights or cords into outdoor outlets—even with adapters |

| Timing & Monitoring | Use timers to limit daily runtime; inspect lights weekly for damaged sockets or frayed wires | Leave lights on unattended overnight or while traveling |

| Power Source | For large displays (>500W), consult an electrician about a dedicated circuit or temporary service panel | Power entire displays from a single power strip or multi-outlet adapter |

Expert Insight: What Electricians See Behind the Scenes

“Most holiday fires I investigate start not with sparks, but with ‘warm’ outlets—people ignore the first sign because nothing’s smoking yet. By the time they smell burning plastic, the damage is done: oxidized terminals, carbon-tracked insulation, and compromised grounding paths. Prevention isn’t about buying fancier lights—it’s about respecting physics. Every watt you add generates heat. Every connection adds resistance. Every extension cord adds voltage drop. There are no exceptions.”

— Marcus Chen, Master Electrician & NFPA Certified Electrical Safety Specialist, 28 years in residential forensics

FAQ: Common Questions About Circuit Overload and Christmas Lights

Can I safely plug multiple light strings into a single power strip?

No—not unless the power strip is explicitly rated for continuous outdoor use *and* its total load (including all connected strings) stays under 80% of the circuit’s capacity. Most retail power strips are rated for 15A/1,800W *peak*, but lack thermal protection for sustained loads. Using one multiplies connection points and increases fire risk significantly. Dedicated outdoor outlets with built-in GFCI/AFCI protection are safer alternatives.

Why do my lights dim when I turn on the tree fan or another appliance?

Dimming indicates voltage drop caused by excessive current draw on the same circuit. This is a clear warning sign: your circuit is overloaded or has high-resistance connections (loose terminals, corroded wires, or undersized conductors). Dimming stresses LED drivers and transformer-based lights, shortening lifespan and increasing failure risk. Immediately reduce the load and inspect connections.

Are solar-powered Christmas lights a safe alternative for overloading concerns?

Solar lights eliminate circuit loading entirely—but they’re unsuitable for primary display lighting. Most produce only 2–5 lumens per bulb, lack consistent brightness in cloudy weather, and have limited runtime (4–6 hours). They work well for pathway accents but cannot replace grid-powered displays. Their batteries also degrade in freezing temperatures, reducing reliability in winter months.

Conclusion: Light Responsibly, Celebrate Confidently

Christmas lights should inspire wonder—not worry. Understanding circuit limits isn’t about restricting joy; it’s about ensuring your traditions continue for decades, not just one season. Overloading isn’t a theoretical risk—it’s a predictable failure mode with measurable symptoms: warmth at outlets, discoloration, buzzing sounds, and inconsistent brightness. These aren’t quirks of holiday magic; they’re physics announcing themselves. By calculating loads honestly, upgrading infrastructure where needed, and treating every connection as a critical safety node, you protect more than your home—you safeguard memories in the making. This year, make safety part of your ritual: test outlets, measure actual wattage, and share these practices with neighbors. Because the most beautiful light is the one that shines steadily, safely, and for years to come.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?