When home cooks slice open a garlic clove and encounter a hard, pale core running through its center, many instinctively discard it—assuming it’s inedible or undesirable. That core is the garlic pit, also known as the garlic germ or central stem, and its presence sparks confusion across kitchens worldwide. Contrary to popular belief, the garlic pit isn’t waste; it’s a natural part of mature garlic with distinct culinary properties. Understanding what the garlic pit is—and whether (or when) to use it—can refine your seasoning techniques, deepen flavor control, and reduce unnecessary food waste. This guide clarifies the botany, taste, function, and practical applications of the garlic pit, empowering cooks to make informed decisions based on desired outcomes.

Definition & Overview

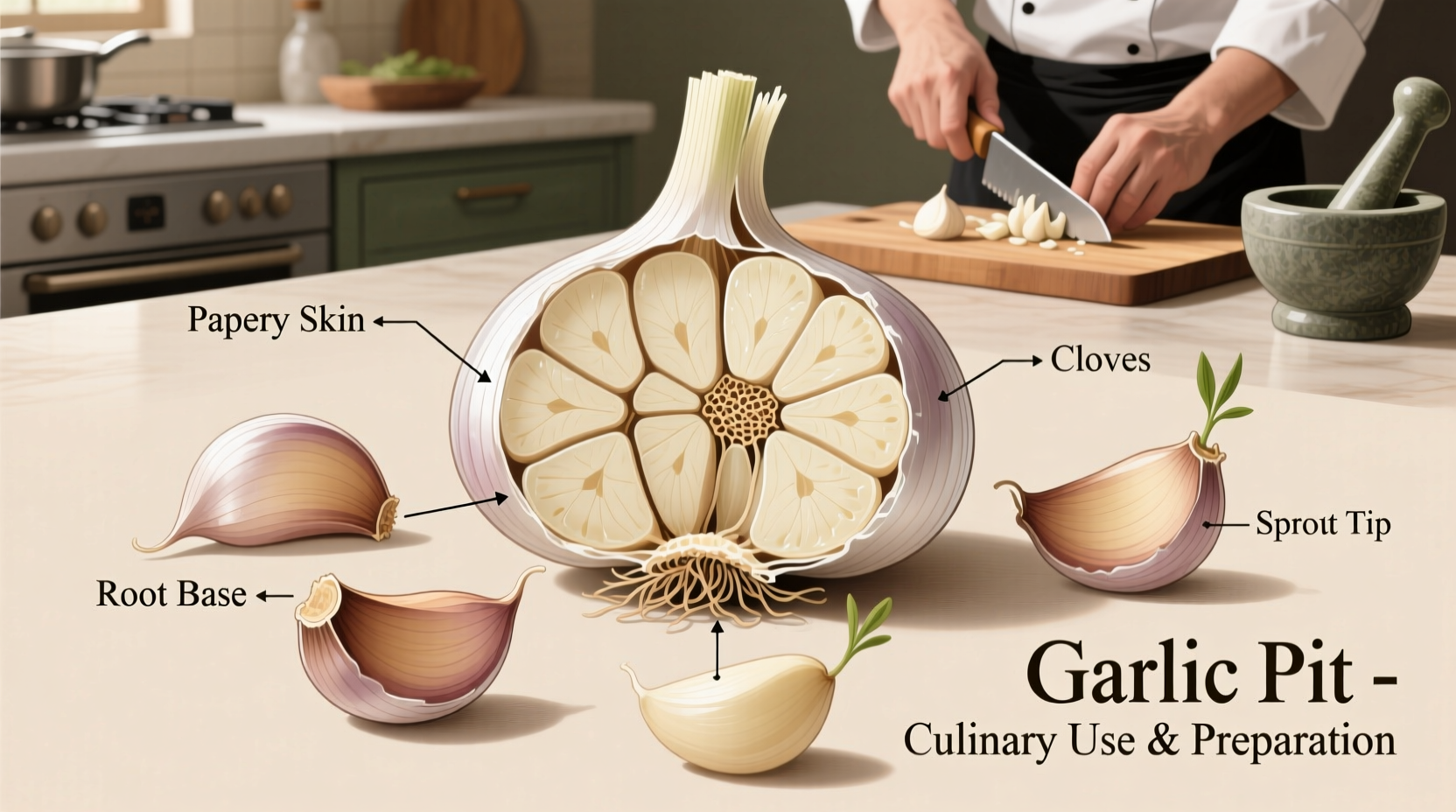

The garlic pit refers to the central, fibrous sprout that develops within individual cloves of mature garlic bulbs (*Allium sativum*). It emerges as the clove ages or begins to germinate, transforming from a barely visible strand into a pronounced, pale-green to yellowish shoot. Unlike the fleshy outer layers of the clove, which are soft and aromatic when crushed, the pit has a woody texture and a sharper, more bitter flavor profile.

Botanically, the garlic pit is the plant’s embryonic growth point—the precursor to a new garlic plant. In younger garlic, such as fresh or “green” garlic harvested in spring, this central core is tender and undeveloped, often indistinguishable from the surrounding clove tissue. However, as garlic cures and stores over time—typically after several weeks post-harvest—the pit elongates and hardens, becoming increasingly prominent in older bulbs commonly found in supermarkets.

In culinary contexts, the garlic pit occupies a gray area: not toxic, not inedible, but texturally and flavor-wise divergent from the rest of the clove. Its use depends on cooking method, dish type, and desired intensity. While many chefs remove it for aesthetic and sensory refinement, others retain it for convenience or in applications where its bitterness mellows or integrates seamlessly.

Key Characteristics

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| Flavor | Bitter, sharp, slightly pungent; more astringent than the clove flesh, especially when raw. |

| Aroma | Less sweet and floral than garlic flesh; carries a green, almost vegetal sharpness. |

| Texture | Fibrous, tough, and rigid—does not break down easily even with prolonged cooking. |

| Color | Pale yellow to light green; becomes more vividly green as the sprout matures. |

| Culinary Function | Acts as a structural element rather than a flavor base; can contribute subtle heat and complexity in long-cooked dishes. |

| Shelf Life Indicator | Larger, greener pits signal older garlic; smaller or absent pits indicate fresher bulbs. |

Practical Usage: How to Use Garlic Pit in Cooking

The decision to keep or remove the garlic pit hinges on three factors: preparation method, dish format, and desired flavor balance. In raw or finely minced applications, the pit's bitterness and toughness stand out, making removal advisable. In slow-cooked or blended dishes, its impact diminishes, and removal becomes less critical.

When to Remove the Garlic Pit

- Raw preparations: In aioli, vinaigrettes, uncooked salsas, or garlic-infused oils, the raw pit imparts an unpleasant bitterness. Always remove it before mincing or grating.

- Fine emulsions: Mayonnaise, pesto, or tapenade benefit from smooth texture and balanced flavor—leaving the pit in can create graininess and off-notes.

- Delicate sauces: Cream-based sauces, butter sauces, or clear broths highlight subtle flavors. An intact pit may introduce unwanted harshness.

When It’s Acceptable to Leave It In

- Slow braises and stews: In dishes like beef bourguignon, lentil dal, or tomato ragù, whole or lightly crushed garlic cloves are often simmered for hours. The pit softens slightly and blends into the background, contributing minimal bitterness.

- Stocks and broths: When garlic is used as an aromatic base and later strained out, the pit doesn’t affect the final product. Removing it beforehand adds unnecessary prep time.

- Rustic roasting: Whole roasted garlic heads are meant to be squeezed from their skins. The softened pit can be eaten along with the flesh or discarded by the diner—no pre-roast removal needed.

Step-by-Step: How to Remove the Garlic Pit

- Peel the garlic clove completely.

- Lay it flat on a cutting board and slice it in half lengthwise, from root end to tip.

- Inspect the center: the pit appears as a pale line or small green shoot.

- Use the tip of a paring knife or your fingernail to lift and pull out the core.

- Proceed with mincing, crushing, or slicing as the recipe requires.

Pro Tip: If you're processing multiple cloves, do the pit removal in batches after peeling. A small knife or specialized garlic tool speeds up the process. For maximum efficiency, reserve the removed pits for stock-making—see below.

Variants & Types of Garlic and Their Pits

Not all garlic produces pits equally. The likelihood and prominence of the pit depend on garlic variety, harvest time, and storage duration.

Hardneck Garlic

Common in farmers markets and cooler climates, hardneck varieties (e.g., Porcelain, Rocambole, Purple Stripe) are more prone to developing large, noticeable pits. They produce a flowering stalk (scape), and their cloves tend to be larger and fewer per bulb. Because they’re often sold closer to harvest, their pits may still be tender—especially in early-season bulbs.

Softneck Garlic

The standard supermarket garlic, softneck (e.g., California White, Silverskin) stores longer and typically has smaller, less developed pits—unless kept for months. These bulbs are bred for shelf stability, so while pits form over time, they’re often thinner and paler.

Green (Spring) Garlic

Harvested young, green garlic resembles scallions with a small, undeveloped bulb. Its central core is tender and edible, lacking the fibrous quality of mature pits. No removal is necessary—use the entire plant like a mild leek or garlic chive.

Elephant Garlic

Despite the name, elephant garlic is more closely related to leeks. Its cloves are massive, and the central pit is thick but milder in flavor. While still firmer than the flesh, it’s less bitter and can be left in for most cooked applications.

| Garlic Type | Pit Development | Removal Recommended? |

|---|---|---|

| Hardneck (mature) | Large, green, fibrous | Yes, especially for raw uses |

| Softneck (aged) | Thin, pale, moderately tough | Optional, depending on dish |

| Green/Spring Garlic | Tender, barely visible | No |

| Elephant Garlic | Thick but mild | Rarely |

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

The garlic pit is often confused with other internal structures in alliums or mistaken for spoilage. Clarifying these distinctions ensures proper handling.

| Ingredient | Difference from Garlic Pit |

|---|---|

| Onion Core | Onions have a dry, papery central axis, but it lacks chlorophyll and does not sprout. It’s removed primarily for texture, not bitterness. |

| Leek Center | The hollow tube of a leek is structurally similar but entirely edible and mild. Not analogous to a pit. |

| Garlic Sprout (Scallion-style) | When garlic grows a full green shoot above ground, that leafy portion is edible and mild—unlike the fibrous internal pit. |

| Mold or Rot | Dark spots, sliminess, or foul odor indicate spoilage. A garlic pit is firm, straight, and pale—not fuzzy or discolored. |

“Many home cooks treat the garlic pit like a defect, but it’s simply a sign of maturity. In my restaurant work, we leave it in stocks and remove it only when purity of flavor is paramount—like in a consommé or raw sauce.” — Claire Nguyen, Executive Chef, Hearth & Vine

Practical Tips & FAQs

Does the garlic pit have any nutritional value?

While limited data exists specifically on the pit, it contains trace amounts of allicin precursors and fiber. However, due to its low consumption volume and tough texture, it contributes minimally to overall nutrition compared to the clove flesh.

Can you eat garlic with a green sprout inside?

Yes. A green sprout (the visible pit) does not mean the garlic is spoiled. The clove may be drier and the pit more bitter, but it remains safe to eat. For best quality, use older garlic in cooked dishes rather than raw ones.

How can I prevent strong pits in garlic?

- Buy garlic in season—late summer through winter—for fresher bulbs.

- Store garlic in a cool, dark, well-ventilated place (not the refrigerator).

- Use older bulbs promptly; rotate stock to avoid long-term storage.

Are there creative uses for removed garlic pits?

Yes. Save them in a freezer bag and use as aromatic additions to vegetable stock, meat bones, or bean pots. Though they won’t dissolve, they release subtle depth during simmering and are strained out at the end—just like bay leaves or peppercorns.

Does roasting eliminate the bitterness of the pit?

Roasting mellows the pit significantly. The high heat caramelizes natural sugars and breaks down some of the harsh compounds, rendering the sprout softer and less assertive. In fully roasted cloves, the pit becomes chewable and blends into the creamy texture.

Is the garlic pit spicy or hot?

Not in the capsaicin sense. Its “heat” is more astringent and pungent—similar to raw radish or mustard greens. It lacks the sulfurous burn of fresh garlic flesh but introduces a different kind of sharpness.

Storage Tip: To delay pit development, store garlic at 60–65°F (15–18°C) with 60–70% humidity. Refrigeration can trigger sprouting, while hot, humid environments accelerate drying and bitterness.

Summary & Key Takeaways

The garlic pit is not a flaw—it’s a natural component of mature garlic with specific sensory traits. Recognizing its role allows for smarter, more efficient cooking practices. Key points include:

- The garlic pit is the central germ or sprout in aged garlic cloves, not a defect or contaminant.

- It has a fibrous texture and bitter, sharp flavor, particularly noticeable in raw applications.

- Removal is essential for refined dishes like aioli or pesto but optional in soups, stews, and roasted preparations.

- Young garlic (green garlic) has no problematic pit—its entire structure is tender and edible.

- Different garlic types develop pits at varying rates, with hardneck varieties showing them more prominently.

- Removed pits can be repurposed in stocks and broths for zero-waste cooking.

Mastering the nuances of ingredients—even seemingly minor ones like the garlic pit—separates functional cooking from truly intentional cuisine. By understanding when to embrace or edit out this core element, you gain finer control over flavor, texture, and ingredient utilization. Next time you peel a clove, pause before discarding the center. Assess the dish, the garlic’s age, and your desired outcome. In doing so, you transform a routine step into a deliberate culinary choice.

Try This: Conduct a side-by-side test: prepare two versions of garlic mashed potatoes—one with pit-free cloves, one with pits intact. Note differences in aftertaste and mouthfeel. You’ll develop a personal threshold for tolerance and preference.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?