Dehydration affects millions of people each year, from athletes pushing through intense workouts to elderly individuals managing chronic conditions. While oral rehydration solutions are often sufficient, intravenous (IV) fluids become essential when rapid or severe fluid replacement is needed. But with multiple types of IV fluids available, determining the best option can be confusing—even for healthcare professionals. This guide breaks down the most common IV fluids used in clinical settings, explains their composition and indications, and helps clarify which solution is best suited for different types of dehydration.

Understanding Dehydration and When IV Fluids Are Needed

Dehydration occurs when the body loses more fluids than it takes in, disrupting electrolyte balance and impairing vital functions. Mild cases can usually be managed with water or oral rehydration salts (ORS), but moderate to severe dehydration—especially when accompanied by vomiting, diarrhea, or altered mental status—requires immediate medical intervention. In these situations, IV fluids deliver water and electrolytes directly into the bloodstream, bypassing the digestive system for faster recovery.

The choice of IV fluid depends on several factors: the severity of dehydration, underlying health conditions, electrolyte imbalances, and whether the patient needs volume expansion, maintenance, or correction of specific deficiencies.

Types of IV Fluids: Composition and Uses

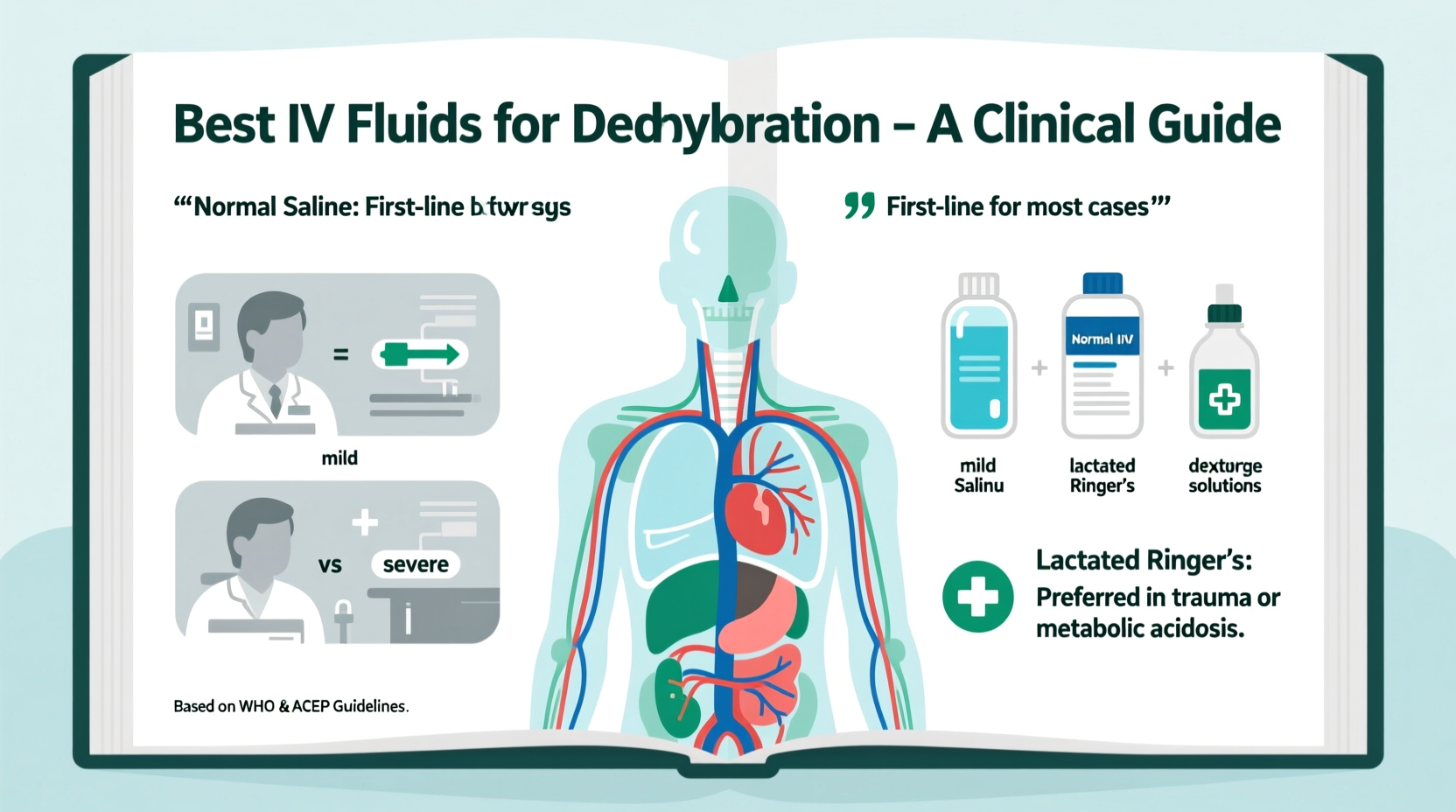

IV fluids are categorized based on their tonicity—how their concentration compares to blood plasma—and their primary components. The three main categories are isotonic, hypotonic, and hypertonic solutions.

Isotonic Solutions

These have a similar concentration to blood plasma and do not cause fluid shifts between compartments. They expand intravascular volume quickly, making them ideal for acute fluid resuscitation.

- Normal Saline (0.9% NaCl): Contains 154 mEq/L of sodium and chloride. Widely used in emergency departments for shock, trauma, and surgical patients due to its rapid volume-expanding effect.

- Lactated Ringer’s (LR): Balanced electrolyte solution containing sodium, potassium, calcium, chloride, and lactate (which converts to bicarbonate). Preferred in burn injuries, pancreatitis, and metabolic acidosis because it more closely mimics extracellular fluid.

- Plasmalyte-A: Similar to LR but contains acetate instead of lactate and has a pH closer to physiological levels. Often chosen in critical care to minimize acid-base disturbances.

Hypotonic Solutions

Lower solute concentration than plasma; they promote cellular hydration by shifting fluid from blood vessels into cells. Commonly used for maintenance therapy in hospitalized patients who can't eat or drink.

- Half-normal saline (0.45% NaCl): Often given with added dextrose (e.g., D5 0.45% NaCl) to prevent hypoglycemia while providing free water for cellular hydration.

Hypertonic Solutions

Higher concentration than plasma, drawing fluid into the bloodstream from tissues. Reserved for specific conditions like severe hyponatremia or cerebral edema.

- 3% Saline: Used cautiously under close monitoring to correct dangerously low sodium levels.

Comparing Common IV Fluids: A Clinical Overview

| Fluid Type | Key Components | Tonicity | Common Indications | Cautionary Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Saline (0.9%) | Na⁺ 154 mEq/L, Cl⁻ 154 mEq/L | Isotonic | Shock, hemorrhage, sepsis | Risk of hyperchloremic acidosis with large volumes |

| Lactated Ringer’s | Na⁺ 130, K⁺ 4, Ca²⁺ 3, Cl⁻ 109, Lactate 28 mEq/L | Isotonic | Burns, trauma, post-op hydration | Avoid in severe liver dysfunction (lactate metabolism) |

| Plasmalyte-A | Na⁺ 140, K⁺ 5, Mg²⁺ 3, Cl⁻ 98, Acetate 27, Gluconate 23 mEq/L | Isotonic | Critical illness, diabetic ketoacidosis | Contains potassium—avoid in renal failure |

| 0.45% Saline | Na⁺ 77, Cl⁻ 77 mEq/L | Hypotonic | Maintenance fluid, hypernatremia | Risk of cerebral edema if overused |

| 3% Saline | Na⁺ 513 mEq/L | Hypertonic | Severe hyponatremia with neurological symptoms | Requires ICU-level monitoring |

“Isotonic crystalloids like Lactated Ringer’s and normal saline are first-line for most cases of acute dehydration. The key is matching the fluid to the patient’s physiology—not just replacing volume, but preserving electrolyte and acid-base balance.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Critical Care Physician

Step-by-Step: How Clinicians Choose the Right IV Fluid

Selecting the optimal IV fluid involves a systematic assessment. Here’s how medical professionals approach the decision:

- Evaluate the Cause of Dehydration: Is it from vomiting, diarrhea, heat exposure, or another condition? Gastrointestinal losses often involve significant sodium and bicarbonate depletion, favoring balanced solutions like LR.

- Assess Volume Status: Look for signs of hypovolemia—low blood pressure, rapid heart rate, poor skin turgor. Isotonic fluids are preferred for volume resuscitation.

- Review Lab Values: Check serum sodium, potassium, creatinine, and arterial blood gases. Hyponatremia may require hypotonic fluids; hypernatremia calls for cautious use of isotonic or hypotonic solutions depending on volume status.

- Consider Underlying Conditions: Patients with heart failure may need restricted fluid administration, while those with liver disease may not metabolize lactate well, making Plasmalyte or normal saline better options.

- Monitor Response: After initiating therapy, reassess vital signs, urine output, and labs within hours. Adjust the fluid type or rate as needed.

Real-World Example: Treating Severe Dehydration in an Elderly Patient

An 82-year-old woman arrives at the emergency room after two days of vomiting and inability to keep fluids down. She appears lethargic, her blood pressure is 90/60 mmHg, heart rate is 118 bpm, and her skin shows poor elasticity. Blood tests reveal elevated sodium (152 mEq/L), increased BUN-to-creatinine ratio, and mild metabolic alkalosis from gastric losses.

The medical team starts her on Lactated Ringer’s at 500 mL/hour to restore intravascular volume and correct electrolyte deficits. Over the next six hours, her blood pressure stabilizes, she becomes more alert, and repeat labs show improving kidney function. Once stable, the team transitions her to oral fluids and adds potassium supplements based on ongoing monitoring.

This case illustrates how Lactated Ringer’s effectively addresses both volume loss and electrolyte imbalance in a real-world setting.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I receive IV fluids at home for dehydration?

In some cases, yes. Home infusion services are available for patients with chronic conditions requiring regular hydration support. However, this requires a prescription and professional oversight to ensure safety and proper fluid selection.

Why not always use normal saline since it’s widely available?

While normal saline is accessible and effective for volume expansion, prolonged or large-volume use can lead to hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis. Balanced crystalloids like Lactated Ringer’s or Plasmalyte are increasingly favored in modern practice for better physiological compatibility.

Are there risks associated with IV fluid therapy?

Yes. Complications include fluid overload (especially in heart or kidney disease), electrolyte imbalances, infection at the IV site, and, in rare cases, air embolism. That’s why IV therapy should be administered under medical supervision with regular monitoring.

Final Thoughts and Recommendations

There is no single “best” IV fluid for all cases of dehydration. The optimal choice hinges on the individual’s clinical condition, lab results, and treatment goals. For most acute scenarios involving volume loss—such as gastroenteritis, trauma, or surgery—Lactated Ringer’s or normal saline are appropriate starting points. However, nuanced cases demand tailored approaches that consider acid-base status, organ function, and ongoing losses.

If you're a patient, understanding your treatment can empower informed conversations with your healthcare provider. If you're a clinician, staying updated on evolving guidelines—like those from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign or Choosing Wisely—can improve outcomes by promoting evidence-based fluid selection.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?