The year 1900 is often cited as a surprising exception in the leap year system: it was divisible by four, yet it was not a leap year. This anomaly confuses many who assume that any year divisible by four automatically qualifies as a leap year. The explanation lies in the refined rules of the Gregorian calendar, introduced to correct inaccuracies in its predecessor, the Julian calendar. Understanding why 1900 wasn’t a leap year reveals the precision behind our modern timekeeping and how science shaped the calendar we use today.

The Problem with the Julian Calendar

Before the Gregorian reform, much of Europe followed the Julian calendar, instituted by Julius Caesar in 46 BCE. It established a simple rule: every year divisible by four would be a leap year, adding an extra day to February every four years. While this system improved upon earlier calendars, it overestimated the length of the solar year.

Astronomers had long known that a true solar year—the time it takes Earth to complete one orbit around the Sun—is approximately 365.2422 days. The Julian calendar, however, assumed a year of exactly 365.25 days. This small discrepancy—just 0.0078 days per year—accumulated over centuries. By the late 1500s, the calendar had drifted about 10 days ahead of the actual seasons. This misalignment affected the calculation of religious holidays like Easter, which depends on the spring equinox.

“Without correction, the calendar would eventually place summer in December in the Northern Hemisphere.” — Dr. Alan Stern, Planetary Scientist

The Gregorian Reform: A More Accurate System

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar to realign the calendar year with the astronomical year. The reform involved two key changes:

- Remove 10 days from October 1582 to reset the vernal equinox to March 21.

- Revise the leap year rule to reduce the average length of the calendar year.

The new leap year algorithm was designed to better approximate the solar year. Instead of adding a leap day every four years without exception, the Gregorian calendar introduced exceptions for century years (years ending in 00).

How the Leap Year Rule Works Today

The current rule for determining leap years in the Gregorian calendar consists of three steps:

- If the year is not divisible by 4, it is a common year.

- If the year is divisible by 4 but not by 100, it is a leap year.

- If the year is divisible by 100, it must also be divisible by 400 to be a leap year.

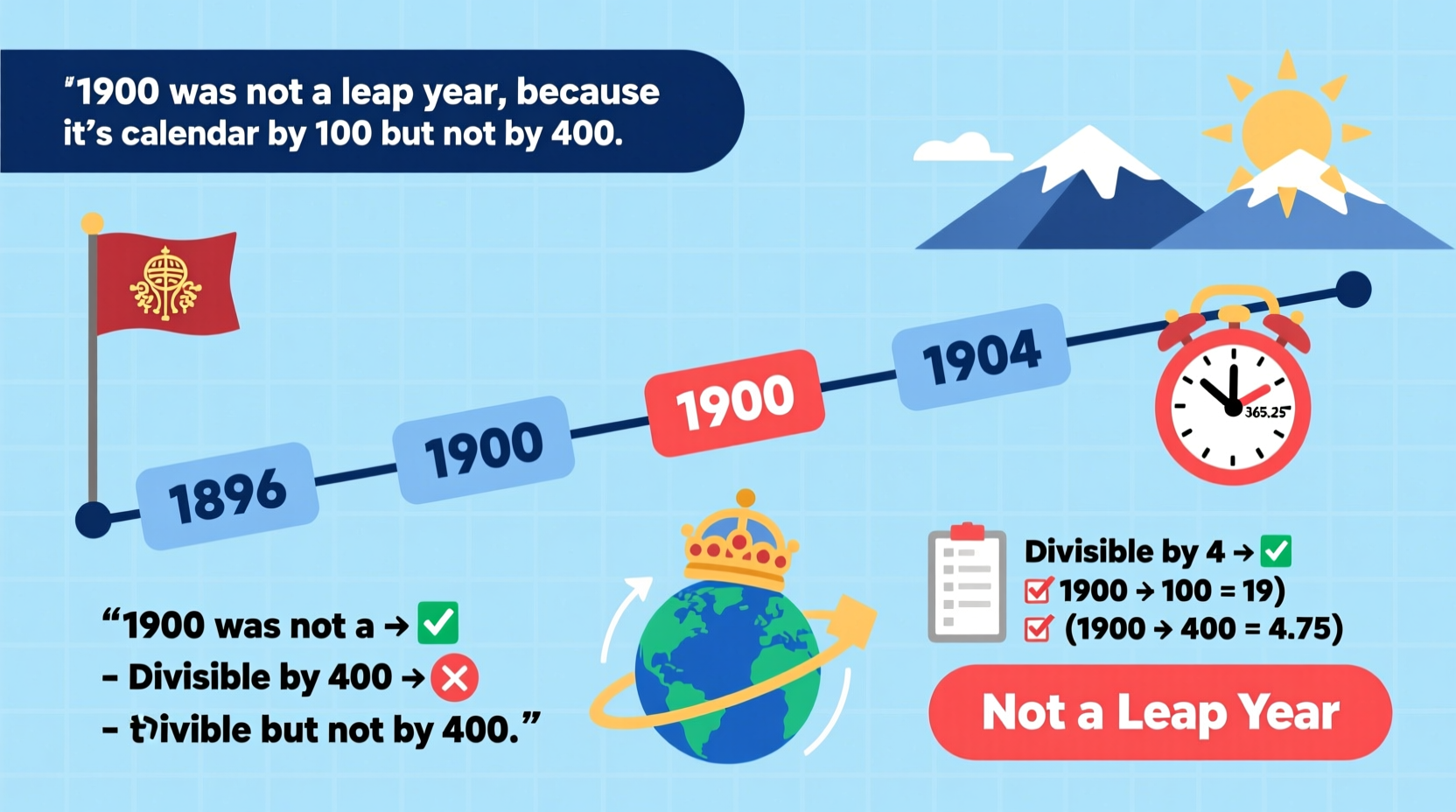

This means that while 1900 was divisible by 4 and by 100, it was not divisible by 400—and therefore not a leap year. In contrast, the year 2000 was a leap year because it met all three criteria, including divisibility by 400.

Examples of Century Years in the Gregorian System

| Year | Divisible by 4? | Divisible by 100? | Divisible by 400? | Leap Year? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1700 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 1800 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 1900 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 2000 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2100 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

This tiered system reduces the average length of the calendar year to 365.2425 days—extremely close to the astronomical 365.2422. The difference is just 26 seconds per year, meaning it will take over 3,000 years for the calendar to drift by a single day.

Real-World Impact: Why It Matters

The accuracy of the Gregorian calendar affects more than just historical trivia. Consider agricultural planning, astronomical observations, and international coordination. A drifting calendar would gradually shift seasonal markers, disrupting planting schedules, school terms, and holiday traditions.

Mini Case Study: The Russian Revolution and Calendar Confusion

Russia continued using the Julian calendar well into the 20th century. When the February Revolution occurred in 1917, it actually took place in March according to the Gregorian calendar. Similarly, the October Revolution happened in November. This discrepancy caused confusion in international reporting and diplomatic records. Russia finally adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1918, skipping 13 days to realign with the rest of Europe. This example shows how calendar systems can influence historical narratives and global communication.

Common Misconceptions About Leap Years

Many people believe leap years occur simply every four years, period. This misunderstanding leads to surprise when they learn that 1900 or 2100 are not leap years. Others think the Gregorian calendar is perfectly accurate forever—but even it requires occasional adjustments.

For instance, leap seconds are occasionally added to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) to account for irregularities in Earth’s rotation. These are separate from leap days but serve a similar purpose: maintaining alignment between human timekeeping and astronomical reality.

Step-by-Step Guide: Is Any Year a Leap Year?

To determine whether a given year is a leap year under the Gregorian system, follow these steps:

- Check divisibility by 4: If the year is not divisible by 4, it is not a leap year. (Example: 2022)

- Check if it's a century year: If it is divisible by 100 (e.g., 1800, 1900), proceed to step 3. Otherwise, it is a leap year. (Example: 2024 ÷ 4 = 506 → leap year)

- Check divisibility by 400: If the century year is divisible by 400, it is a leap year. If not, it is not. (Example: 1900 ÷ 400 = 4.75 → not a leap year; 2000 ÷ 400 = 5 → leap year)

This logical sequence ensures consistent application across centuries and prevents cumulative drift.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did we switch from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar?

The Julian calendar’s overestimation of the solar year caused seasonal drift. By the 1500s, the equinoxes were occurring earlier in the calendar, affecting the timing of Easter. The Gregorian reform corrected this by refining leap year rules and removing accumulated excess days.

Will the Gregorian calendar ever need another update?

While highly accurate, the Gregorian calendar still gains about one day every 3,236 years. Future civilizations may need to adjust it, but for now, no official plans exist. Leap seconds are used for short-term synchronization with Earth’s rotation.

Was February 29, 1900 a valid date?

No. Since 1900 was not a leap year, February had only 28 days. Anyone born on February 29 must wait four years to celebrate on their actual birth date, but those born in 1900 didn’t face this issue—because that date didn’t exist that year.

Conclusion: Precision in Timekeeping

The fact that 1900 was not a leap year is not an error—it’s a feature of a sophisticated system designed to harmonize human calendars with the rhythms of nature. The Gregorian calendar reflects centuries of astronomical observation and mathematical refinement. Its leap year rules, though sometimes counterintuitive, ensure that our seasons stay where they belong and our dates remain reliable across generations.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?