Action potentials are the electrical signals that neurons use to communicate across the nervous system. These rapid, temporary changes in membrane potential allow information to travel from sensory receptors to the brain and from the brain to muscles and glands. A critical feature of action potentials is their unidirectional movement—once initiated, they travel down the axon in only one direction: from the cell body toward the axon terminals. This might seem like a minor detail, but it’s essential for accurate and efficient neural signaling. Without this one-way propagation, signals could double back, causing confusion, delays, or even chaotic neural activity.

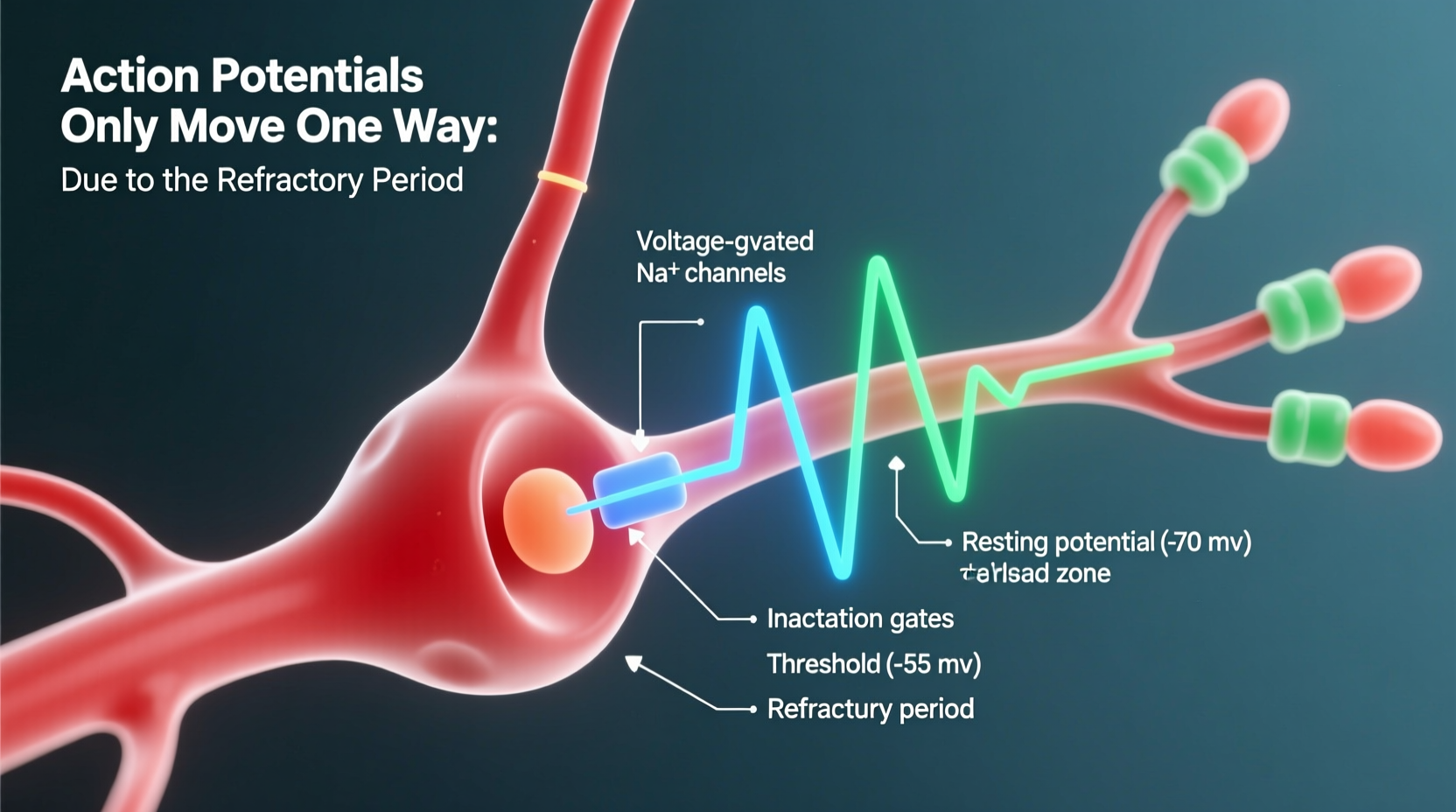

The reason action potentials move in only one direction lies in the physiology of voltage-gated ion channels and the refractory periods that follow each signal. Understanding this mechanism reveals not just how neurons function reliably, but also how the nervous system maintains precision in everything from reflexes to conscious thought.

The Basics of Action Potential Propagation

An action potential begins when a neuron’s membrane potential reaches a threshold—typically around -55 mV—triggering the opening of voltage-gated sodium (Na⁺) channels. Sodium ions rush into the cell, causing rapid depolarization. This spike in voltage then prompts nearby voltage-gated Na⁺ channels further down the axon to open, propagating the signal forward.

At first glance, this process seems symmetrical: if the influx of Na⁺ at one point can trigger adjacent channels on either side, why doesn’t the signal travel backward as well as forward? The answer lies in what happens immediately after an action potential passes through a segment of the axon.

Refractory Periods: The Key to One-Way Travel

After an action potential, a region of the axon enters a brief period during which it cannot generate another action potential. This is known as the **refractory period**, and it comes in two phases:

- Absolute refractory period: During this phase, no new action potential can be initiated, regardless of stimulus strength. Voltage-gated Na⁺ channels are inactivated—they have closed and cannot reopen immediately.

- Relative refractory period: Following the absolute phase, a stronger-than-usual stimulus may trigger another action potential, but it’s more difficult. Some Na⁺ channels have recovered, but the membrane is hyperpolarized due to potassium (K⁺) efflux, making it harder to reach threshold.

These refractory periods ensure that once an action potential has passed a given point on the axon, that segment becomes temporarily unresponsive. As a result, the next segment down the line—still at resting potential—is the only area capable of firing. This forces the signal to move forward and prevents it from reversing course.

Role of Voltage-Gated Channel States

Voltage-gated Na⁺ channels have three distinct states: closed (resting), open (activated), and inactivated. When the membrane depolarizes, these channels transition from closed to open. But shortly after opening, they automatically enter the inactivated state, during which they cannot reopen—even if the membrane remains depolarized.

This inactivation is crucial. While the upstream portion of the axon (behind the action potential) is in the refractory phase with inactivated Na⁺ channels, the downstream portion is still polarized and ready to respond. Thus, the wave of depolarization can only proceed forward.

In myelinated axons, where action potentials jump between nodes of Ranvier (saltatory conduction), the same principle applies. Each node fires sequentially, and once a node has fired, it enters its refractory period, ensuring the signal leaps forward—not backward.

“Without the refractory period, neural circuits would misfire constantly. It's the biological equivalent of a diode in an electrical circuit.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Neurophysiology Researcher, Stanford University

Step-by-Step: How an Action Potential Moves Forward

Here’s a chronological breakdown of how unidirectional propagation occurs:

- Stimulus arrives at the axon hillock, depolarizing the membrane to threshold.

- Voltage-gated Na⁺ channels open at the initial segment, allowing Na⁺ influx and generating the rising phase of the action potential.

- Depolarization spreads to the adjacent downstream segment, triggering its voltage-gated Na⁺ channels.

- Meanwhile, the upstream segment enters the absolute refractory period—its Na⁺ channels are inactivated.

- The action potential thus cannot move backward because the previous segment is unexcitable.

- The signal continues down the axon in a wave, with each segment activating the next while becoming temporarily inactive itself.

- Repolarization follows via K⁺ efflux, and the Na⁺/K⁺ pump restores ion gradients over time.

Why Bidirectional Signaling Doesn't Happen (Even Though It Could)

Under experimental conditions—such as when stimulating the middle of an axon—action potentials can indeed travel in both directions. This demonstrates that the axon membrane is capable of bidirectional conduction. However, under normal physiological conditions, action potentials start at the axon hillock and never initiate in the middle.

Because initiation begins at one end and the refractory period blocks retrograde movement, the system is designed to enforce unidirectionality. In rare cases, such as in some sensory neurons or during pathological states (e.g., epilepsy), abnormal signaling can occur, but these are exceptions that prove the rule.

Common Misconceptions About Neural Signaling

Some believe that myelin alone ensures one-way travel. While myelin speeds up conduction via saltatory propagation, it does not prevent backward movement. The real safeguard is still the refractory period.

Others assume that neurons fire continuously. In reality, the refractory period limits the maximum firing rate of a neuron, which helps regulate signal frequency and prevents signal overlap.

| Misconception | Reality |

|---|---|

| Action potentials can naturally reverse direction. | No—refractory periods block backward propagation under normal conditions. |

| Myelin directs signal flow. | Myelin speeds conduction but doesn’t control direction; refractoriness does. |

| All parts of the neuron can initiate action potentials. | Initiation typically occurs only at the axon hillock, which has the lowest threshold. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can action potentials ever travel backward?

Yes—but only experimentally or in specific neural circuits. For example, in some dendrites or during certain forms of synaptic plasticity, backpropagating action potentials occur. However, these are specialized cases and do not interfere with normal forward signaling in the axon.

What happens if the refractory period didn’t exist?

Signals could reverberate along the axon, leading to repeated firing, signal collision, and disrupted communication. The nervous system would lose precision, potentially causing muscle spasms, sensory distortion, or seizures.

Does the strength of the stimulus affect direction?

No. Action potentials are all-or-none events. Once threshold is reached, the signal propagates fully in one direction. Stimulus strength affects firing frequency, not amplitude or direction.

Practical Implications in Medicine and Research

Understanding unidirectional propagation has clinical relevance. For instance, in nerve conduction studies, doctors assess the speed and integrity of action potentials to diagnose conditions like multiple sclerosis or peripheral neuropathy. Abnormal bidirectional signaling or delayed conduction can indicate demyelination or channelopathies.

Moreover, drugs that alter sodium channel function—such as local anesthetics or anti-seizure medications—work by prolonging inactivation or blocking channels, effectively extending refractory periods and reducing neuronal excitability.

Conclusion: Precision Through Design

The one-way movement of action potentials is not accidental—it’s a fundamental design feature of the nervous system. By combining strategic initiation at the axon hillock, rapid voltage-gated channel dynamics, and mandatory refractory periods, neurons ensure that signals travel swiftly and accurately to their targets.

This directional fidelity allows you to react to stimuli without delay, recall memories without interference, and move your body with coordination. It’s a quiet miracle of biology that most never think about—until something goes wrong.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?