You reach for the doorknob after walking across the carpet, and—zap—a sudden jolt shoots through your finger. Or maybe you pull a sweater over your head and hear crackling sounds like miniature lightning strikes. These everyday shocks are caused by static electricity, a phenomenon so common it's often dismissed as a minor annoyance. But behind these tiny zaps lies a fascinating interplay of physics, materials, and environmental conditions. Understanding why you’re getting shocked isn’t just about curiosity—it’s the first step toward reducing those uncomfortable surprises.

The Science Behind Static Electricity

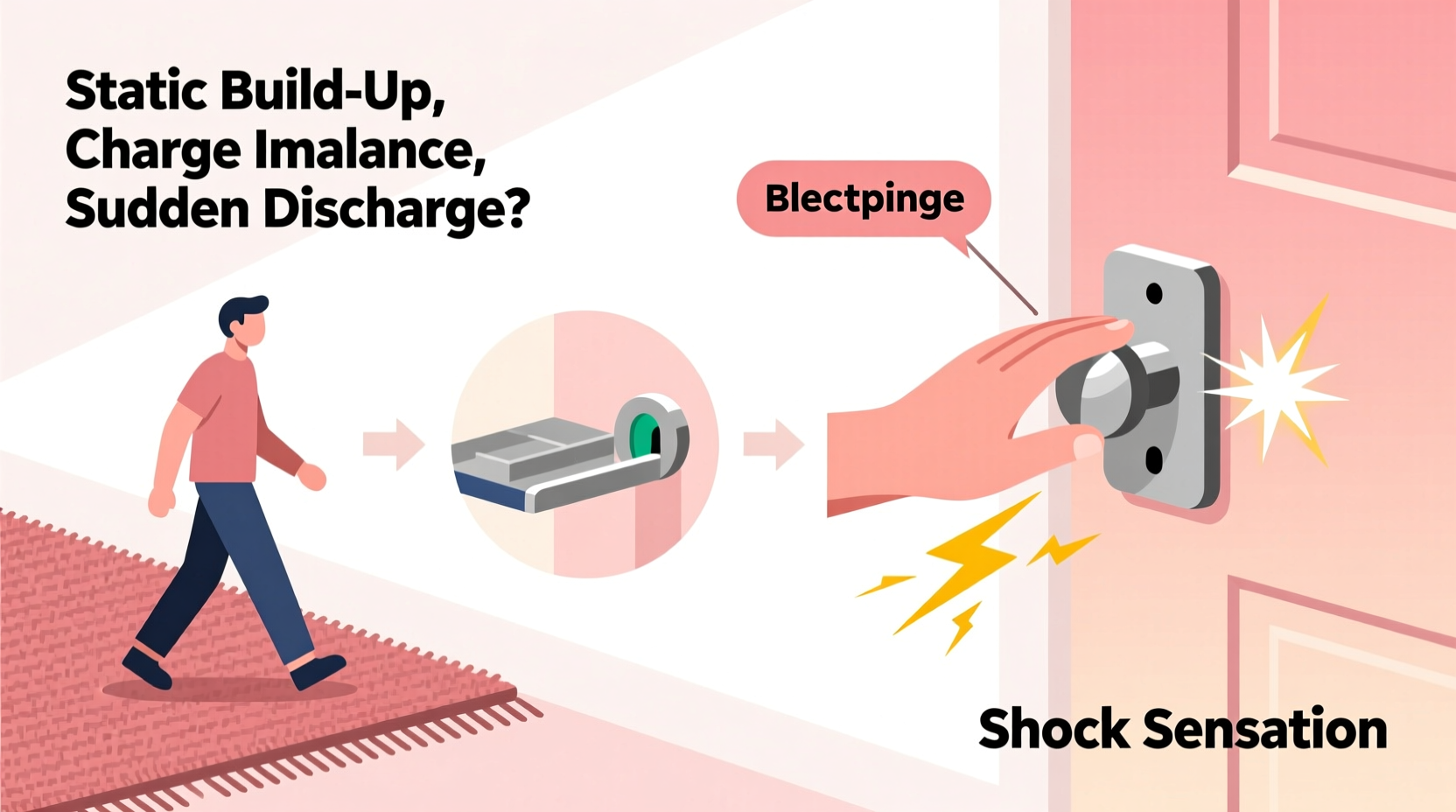

Static electricity occurs when there is an imbalance of electric charges on the surface of a material. Unlike current electricity, which flows through wires, static electricity stays in one place until it discharges—often through you. This buildup happens through a process called triboelectric charging, where two different materials come into contact and then separate. During this interaction, electrons transfer from one material to another.

For example, when you walk across a synthetic carpet in rubber-soled shoes, your body picks up extra electrons. Your body becomes negatively charged. When you touch a metal doorknob—a good conductor—the excess electrons jump from your hand to the knob, creating a spark. That spark is what you feel as a shock.

The strength of the shock depends on several factors: the amount of charge built up, the conductivity of the materials involved, and the humidity in the air. Dry environments make static buildup more likely because moisture in the air normally helps dissipate charges before they accumulate.

“Static shocks are essentially miniature lightning bolts—same principle, vastly smaller scale.” — Dr. Alan Pierce, Physicist and Electromagnetism Researcher

Common Situations That Cause Static Shocks

While any insulating material can generate static under the right conditions, certain daily activities increase your risk:

- Walking on synthetic carpets: Nylon and polyester fibers easily transfer electrons to your shoes and body.

- Sliding off a vinyl or leather car seat: Friction between clothing and upholstery builds charge quickly.

- Drying clothes in a tumble dryer: Synthetic fabrics rub together, generating static that lingers after removal.

- Touching electronics or metal surfaces in dry weather: Low humidity allows charges to build without natural dissipation.

- Removing plastic packaging or tape: Peeling apart adhesive layers separates charges rapidly.

Environmental and Personal Factors at Play

Not everyone experiences static shocks equally. Some people seem to attract them more than others. While no one is inherently “more conductive,” personal habits and surroundings play a major role.

Low indoor humidity—common in winter due to heating systems—is the biggest contributor. Air with less than 40% relative humidity acts as an insulator, preventing built-up charges from leaking away gradually. In contrast, humid summer air reduces static incidents significantly.

Your clothing choices also matter. Wearing multiple layers of synthetic fabrics (like polyester, acrylic, or nylon) increases friction and electron transfer. Wool sweaters, while warm, are notorious for generating static when rubbed against cotton or silk.

Even footwear influences your likelihood of shocking. Rubber-soled shoes insulate you from the ground, preventing charge from escaping into the floor. Leather soles, on the other hand, allow some grounding, especially on conductive surfaces.

| Factor | Increase Risk? | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Dry indoor air (<40% RH) | Yes | Lack of moisture prevents natural charge dissipation |

| Synthetic clothing | Yes | Materials easily gain/lose electrons through friction |

| Rubber-soled shoes | Yes | Insulate body, trapping charge |

| Carpeted floors | Yes | Frequent contact and separation with shoes |

| Humid environment (>60% RH) | No | Moisture conducts charge away harmlessly |

How to Reduce or Prevent Static Shocks

Eliminating static electricity entirely may not be possible, but you can drastically reduce its occurrence with simple changes. Here’s a step-by-step guide to minimizing unwanted zaps:

- Use a humidifier indoors: Maintain indoor humidity between 40% and 60%. This allows charges to dissipate naturally through the air.

- Choose natural-fiber clothing: Wear cotton, linen, or silk instead of synthetics. If wearing wool, layer it over cotton to reduce direct friction.

- Treat carpets and upholstery: Apply anti-static sprays to rugs and furniture. These contain compounds that increase surface conductivity.

- Moisturize your skin: Dry skin has higher resistance, making shocks more intense. Regular use of lotion helps your body release charge gradually.

- Ground yourself before touching metal: Touch a wall, wooden surface, or use a key to discharge safely before grabbing a doorknob.

- Wear leather-soled shoes indoors: They allow slight grounding compared to rubber soles.

- Add fabric softener when washing clothes: It coats fibers with a conductive layer, reducing static cling and shocks.

Mini Case Study: Office Worker’s Winter Shock Problem

Sarah, a graphic designer working in a downtown office building, started experiencing frequent shocks every time she touched her computer or filing cabinet during December. Her workspace had wall-to-wall synthetic carpet, and the building’s heating system kept the air extremely dry. She wore wool socks and rubber-soled boots indoors.

After tracking her routine, she realized the shocks occurred mostly mid-morning, after walking from the break room back to her desk. By introducing a desktop humidifier, switching to cotton-blend socks, and using a metal paperclip to discharge before touching her monitor, her shocks dropped from nearly ten per day to less than one per week within three days.

FAQ: Common Questions About Static Electricity

Can static electricity harm me?

Generally, no. The shocks from everyday static discharge are high in voltage (up to 25,000 volts) but extremely low in current and duration. They pose no real danger to healthy individuals. However, people with sensitive medical devices like pacemakers should consult their doctor, though modern devices are well-shielded.

Why do I get shocked more in winter?

Winter air is drier, both outdoors and indoors due to heating. Low humidity prevents static charges from leaking into the air, allowing them to build up on your body and clothing. Combine that with heavy layers and synthetic fabrics, and shocks become much more common.

Do some people generate more static than others?

Not inherently. Differences come down to behavior and environment—what you wear, how dry the air is, and how much you move across insulating surfaces. Someone who wears rubber-soled shoes on carpet all day will experience more shocks than someone in leather shoes on hardwood.

Conclusion: Take Control of Static, One Zap at a Time

Getting shocked by static electricity isn't random—it's predictable, preventable, and largely within your control. By understanding how charge builds and discharges, you can adjust your environment, clothing, and habits to minimize discomfort. Small changes like using a humidifier, choosing natural fabrics, or grounding yourself before touching metal can transform your daily experience, especially during dry months.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?