Height is a complex trait shaped by a combination of genetics, environment, nutrition, and evolutionary history. While it's inaccurate to generalize all Asian populations as \"short,\" many East and Southeast Asian groups do tend to have lower average heights compared to some Western populations. This article examines the biological, historical, and cultural factors that contribute to this trend, focusing on genetic inheritance, evolutionary adaptation, and long-term dietary patterns.

The Global Picture of Human Height

Human height varies significantly across regions. According to global health studies, the Netherlands has one of the tallest average male heights at around 183 cm (6 feet), while countries like Indonesia and the Philippines report averages closer to 158–163 cm (5'2\"–5'4\"). East Asian nations such as China, Japan, and South Korea fall somewhere in between—historically on the shorter end but with rapid increases in recent decades.

This variation isn't static. Average heights have changed dramatically over the past century due to improvements in public health and nutrition. For example, Japanese men born in the 1980s are about 10 cm taller than those born in the early 1900s. Such shifts highlight that while genetics play a foundational role, environmental factors can powerfully influence how genes are expressed.

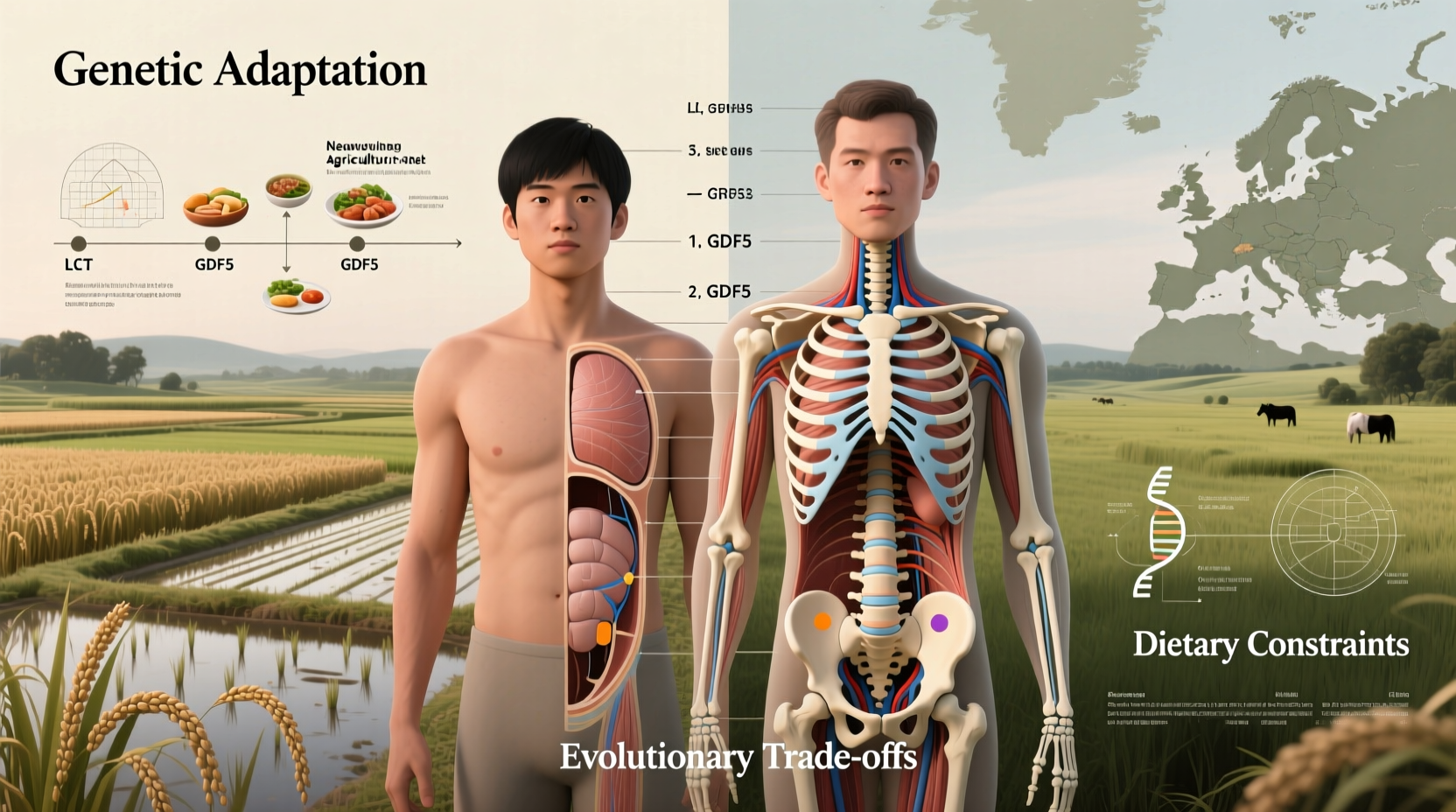

Genetic Factors Influencing Stature

DNA accounts for an estimated 60–80% of height variation. Scientists have identified hundreds of genetic markers associated with height, many located in or near genes involved in bone growth, cartilage development, and hormonal regulation.

Some of these variants are more common in certain populations. For instance, a 2014 study published in Nature Genetics found that East Asians carry higher frequencies of alleles linked to reduced linear growth, particularly in the GDF5 and EFEMP1 genes. These genes regulate skeletal development and joint formation. One variant of GDF5, known as rs143384, is present in over 70% of East Asians but less than 20% of Europeans.

“Population-specific genetic variants evolved in response to local environments and lifestyles. The same gene that may limit height could also confer advantages in mobility or energy efficiency.” — Dr. Sarah Tishkoff, Geneticist, University of Pennsylvania

It’s important to emphasize that “shorter” does not mean “deficient.” Evolution selects traits based on survival and reproductive success, not arbitrary ideals of size. In many ancestral environments, smaller stature offered distinct benefits.

Evolutionary Pressures and Body Size

Bergmann’s Rule in biology states that animals (including humans) in colder climates tend to have larger body masses to conserve heat, while those in warmer regions evolve smaller frames to dissipate heat more efficiently. Much of East and Southeast Asia lies in tropical and subtropical zones, where a compact body shape supports better thermoregulation.

Additionally, smaller bodies require fewer calories. In agrarian societies historically reliant on rice cultivation—where caloric surplus was rare—a lower energy demand improved survival during famines and food shortages. Over generations, natural selection may have favored individuals whose growth patterns aligned with resource availability.

Island dwarfism offers another parallel. On islands with limited resources, large mammals often evolve into smaller forms. While humans didn’t undergo extreme dwarfism, similar selective pressures likely influenced regional body size trends.

Dietary Patterns Across Generations

Nutrition is perhaps the most impactful environmental factor in determining height. Chronic protein deficiency, especially in childhood, can severely stunt growth. Traditional Asian diets, while rich in carbohydrates like rice and noodles, were historically low in animal protein, dairy, and certain micronutrients critical for bone development—such as calcium, vitamin D, and zinc.

In rural China before the 1980s, meat consumption averaged less than 10 kg per person annually. Compare that to modern levels exceeding 60 kg, and the correlation with rising stature becomes clear. Children who grow up with consistent access to diverse proteins and fortified foods reach their full genetic height potential more reliably.

| Era | Typical Diet (East Asia) | Average Male Height (cm) |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-1950 | Rice-based, low animal protein | 155–160 |

| 1950–1980 | Gradual increase in dairy/meat | 160–168 |

| Post-2000 | Balanced, diversified, urban diets | 170–173 |

This nutritional transition explains much of the “height boom” seen in countries like South Korea, which now boasts one of the fastest-growing average heights globally. Korean males born in 2000 are nearly 173 cm tall on average—comparable to many European nations.

Urbanization, Healthcare, and Modern Shifts

Beyond diet, modernization has accelerated height gains through improved sanitation, reduced childhood disease, and universal healthcare. Chronic infections and intestinal parasites—once common in densely populated agricultural regions—can impair nutrient absorption and disrupt growth hormones.

As vaccination rates increased and clean water became standard, children experienced fewer growth interruptions. Combined with school meal programs and prenatal care, these advances created optimal conditions for reaching maximum height potential.

Consider this real-world example:

Mini Case Study: The Korean Height Surge

In the 1950s, following the Korean War, South Korea was one of the poorest nations in the world. Malnutrition was widespread, and the average adult male stood just 161 cm tall. Today, thanks to economic development, national school lunch programs, and strong emphasis on child health, South Korean men average 172.8 cm—taller than their American counterparts under age 30. This transformation occurred within two generations, underscoring the power of environment over inherited limitations.

Common Misconceptions About Asian Height

- Myth: Asians are genetically destined to be short.

Truth: Genes set a range, but environment determines where within that range a person falls. - Myth: Short stature indicates poor health.

Truth: Many shorter populations have high life expectancy and low chronic disease rates. - Myth: All Asians are short.

Truth: There is significant diversity—from the relatively taller Central Asians to the shorter Indigenous groups in Southeast Asia.

What Can Be Done? A Practical Checklist

For parents, caregivers, or policymakers interested in supporting healthy growth, here’s a concise action plan:

- Ensure children consume adequate protein daily (e.g., eggs, fish, legumes, lean meats).

- Promote fortified foods or supplements if dairy intake is low (calcium, vitamin D).

- Schedule regular pediatric check-ups to monitor growth curves.

- Encourage outdoor play to boost vitamin D synthesis and physical development.

- Address intestinal health—treat parasitic infections and support gut microbiome balance.

- Support breastfeeding in infancy, which correlates with healthier growth trajectories.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Asians getting taller over time?

Yes, significantly. Due to improved nutrition and healthcare, average heights in countries like China, Japan, and South Korea have increased by 5–12 cm over the last century. The trend continues, especially in urban areas.

Is there a ‘best’ height for health?

No single height is universally healthier. Extremely tall or short individuals may face specific risks, but within the normal range, lifestyle factors like diet, exercise, and stress matter far more than stature.

Do genetics determine everything about height?

No. While genetics provide a blueprint, epigenetic factors—like maternal nutrition, stress, and toxin exposure during pregnancy—can influence how height-related genes are activated. Environment remains a powerful modifier.

Conclusion: Beyond Stereotypes, Toward Understanding

The question of why some Asian populations are shorter cannot be answered with a single cause. It emerges from deep-rooted genetic adaptations, historical dietary constraints, and ecological realities. But today, with globalization and improved living standards, many of these limitations are fading.

Instead of viewing height through a lens of deficiency, we should recognize it as a dynamic trait shaped by both nature and nurture. As science continues to unravel the interplay between DNA and environment, one thing is clear: human potential is not measured in centimeters.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?