Baseball is often celebrated for its traditions, precision, and uniformity—yet one of its most striking features is the lack of standardization in field dimensions. Unlike sports such as football or soccer, where playing fields adhere to strict size regulations, baseball parks vary dramatically in layout, fence distances, and outfield shapes. Fenway Park’s Green Monster looms just 310 feet from home plate down the left-field line, while Minute Maid Park’s Tal's Hill once created a unique challenge in center field. These differences aren’t flaws—they’re part of the game’s charm and strategic depth. Understanding why baseball field dimensions differ requires exploring historical evolution, architectural constraints, competitive balance, and even psychological impact on players.

The Historical Roots of Variable Field Dimensions

When baseball emerged in the 19th century, it was played in open lots, city parks, and makeshift fields with no governing standards. The first official rules, codified by Alexander Cartwright in 1845, specified the distance between bases (90 feet) and the pitcher’s mound to home plate (originally 45 feet, later adjusted), but they said nothing about outfield boundaries. This omission allowed early ballparks to be shaped by available land, urban layouts, and local preferences.

As cities grew and professional teams established permanent homes, ballpark construction became constrained by geography and real estate. For example, Wrigley Field in Chicago was built within a tight city block, resulting in a shorter right-field porch (346 feet) and an iconic ivy-covered wall. Similarly, Fenway Park’s asymmetrical design accommodated Lansdowne Street, which runs directly behind the left-field wall. These physical limitations made cookie-cutter designs impossible and led to enduring idiosyncrasies.

MLB Rules and Minimum Standards

Despite the variation, Major League Baseball (MLB) does enforce baseline requirements. According to Rule 2.01 of the Official Baseball Rules, the infield must be a perfect square with 90-foot sides, and the pitcher’s mound must sit precisely 60 feet, 6 inches from home plate. However, the rulebook only mandates that the outfield fence be “a minimum of 250 feet from home plate,” with a recommended minimum of 320 feet along the foul lines and 400 feet in center field. These guidelines are not strictly enforced, allowing teams significant leeway.

This regulatory flexibility means that while all MLB fields share core geometric elements, their outfield configurations remain highly individualized. No two major league parks have identical dimensions, and many feature irregularities such as angled walls, varying wall heights, and oddly placed obstacles.

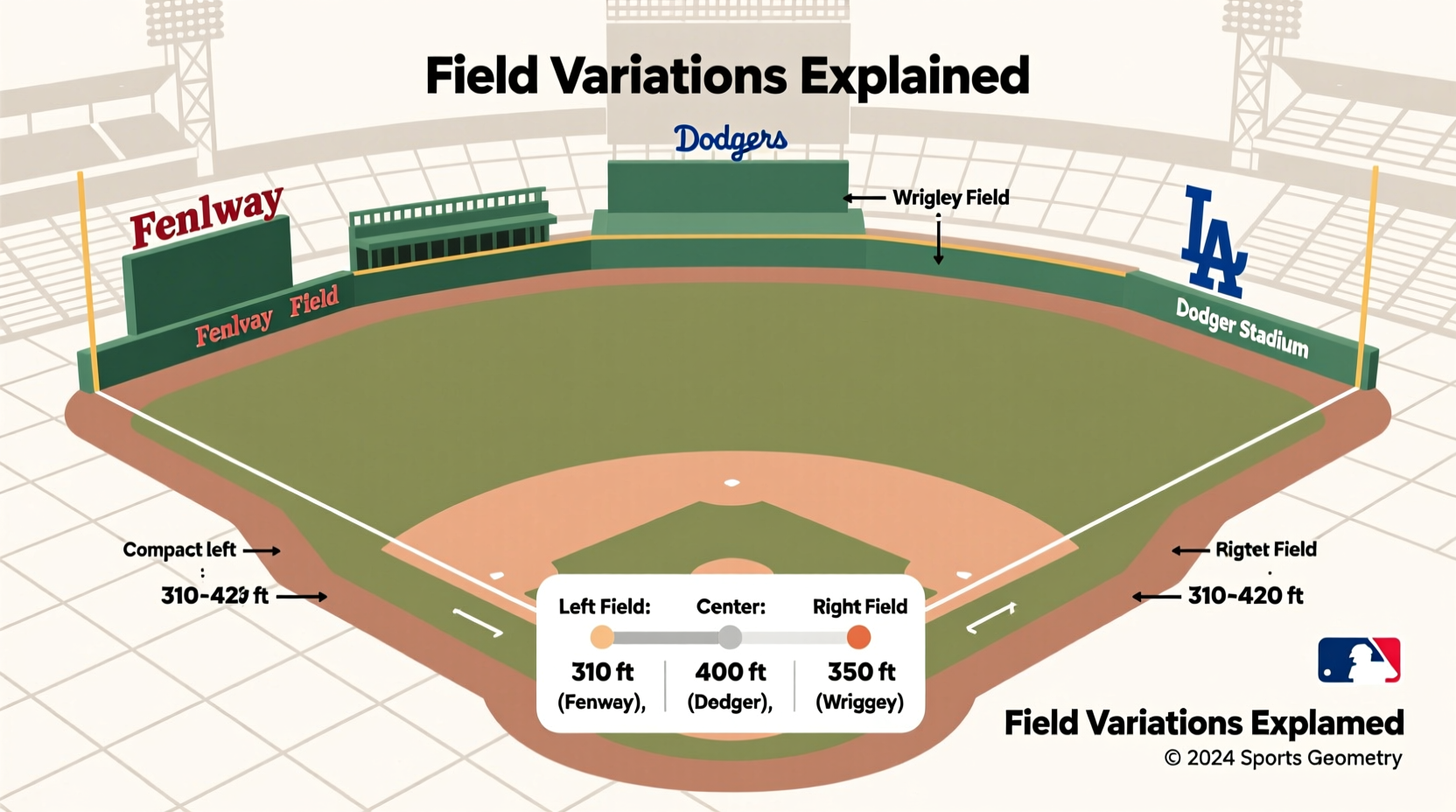

A Comparison of Iconic Ballpark Dimensions

| Ballpark | Left Field (ft) | Center Field (ft) | Right Field (ft) | Notable Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fenway Park (Boston) | 310 | 420 | 302 (Pesky’s Pole) | Green Monster (37' high wall) |

| Yankee Stadium (New York) | 318 | 408 | 314 | Short right field favors left-handed power |

| Wrigley Field (Chicago) | 355 | 400 | 346 | Ivy-covered brick walls |

| Oracle Park (San Francisco) | 309 | 400 | 330 | “Splash Hits” into McCovey Cove |

| Globe Life Field (Texas) | 332 | 400 | 326 | Symmetrical, retractable roof |

The table highlights how even modern stadiums retain personality. Oracle Park, for instance, has one of the shortest left-field fences in the league, encouraging home runs toward the bay—so much so that fans track “splash hits” when balls land in the water. In contrast, the original Yankee Stadium was famously tough on right-handed hitters due to its cavernous right-center field, known as “Death Valley.”

Strategic Impacts of Field Variation

Different dimensions directly influence team strategy, player development, and game outcomes. A stadium with short porches in left field, like Fenway, rewards left-handed pull hitters who can take advantage of the proximity to the wall. Players like Ted Williams and David Ortiz thrived in this environment. Conversely, spacious outfields such as those at Comerica Park in Detroit suppress home runs and favor pitchers and defensive specialists.

Front offices consider ballpark effects when building rosters. The Colorado Rockies, who play at Coors Field—a high-altitude park with thin air and a hitter-friendly environment—often prioritize strong pitching and defensive talent to offset the natural offensive inflation. Meanwhile, the Oakland Athletics under Billy Beane famously leveraged analytics to identify undervalued players whose skills translated well regardless of park effects.

“Every ballpark tells a story. The dimensions shape not just how the game is played, but how it’s remembered.” — John Thorn, Official Historian of Major League Baseball

Modern Trends and the Push for Consistency

In recent decades, there has been a trend toward more standardized, fan-friendly designs. Retro-classic ballparks like PNC Park in Pittsburgh and American Family Field in Milwaukee blend traditional aesthetics with modern amenities, but they still embrace asymmetry and local character. At the same time, some newer stadiums, particularly in warm climates with retractable roofs (e.g., Chase Field, Globe Life Field), adopt more symmetrical dimensions to create neutral playing conditions.

Yet even these attempts at balance don’t eliminate variation. Teams continue to tweak dimensions during renovations—sometimes shrinking them to boost offense, other times expanding them to aid pitching staffs. For example, the Los Angeles Angels reduced the distance to left-center field at Angel Stadium in the 1990s to help their power hitters, only to reverse course years later when the change led to excessive home runs.

Real Example: The Case of Coors Field

No discussion of field variation is complete without examining Coors Field in Denver. At over 5,200 feet above sea level, the air is thinner, offering less resistance to batted balls. While its dimensions (347 ft to left, 390 to center, 352 to right) are not extreme, the environmental factor turns routine fly balls into home runs. To counteract this, the Rockies store baseballs in humidors to reduce bounce and elasticity. Even so, the park remains one of the most hitter-friendly in baseball, altering player performance metrics and complicating Hall of Fame evaluations for players who spent significant time there.

This case illustrates that field variation isn’t just about measurements—it’s about context. Altitude, wind patterns, sun angles, and even crowd noise contribute to the uniqueness of each venue.

FAQ

Do all MLB fields have the same infield size?

Yes. All Major League Baseball fields have exactly 90-foot basepaths and a pitcher’s mound positioned 60 feet, 6 inches from home plate. This consistency ensures fairness in gameplay mechanics like stealing and bunting.

Can teams change their field dimensions?

Yes. Teams can modify outfield fence positions during renovations. For example, the New York Mets brought in the fences at Citi Field in 2012 to increase home run rates after criticism that the park was too pitcher-friendly.

Why don’t they standardize all fields?

Standardization would erase the individual identity of ballparks, which are deeply tied to team history, city culture, and fan experience. The variation adds strategic richness and unpredictability that many purists cherish.

Conclusion

The diversity of baseball field dimensions is not a flaw—it’s a feature. From the shadowed corners of old urban parks to the sleek, engineered layouts of modern domes, each ballpark offers a distinct canvas for the game. These variations challenge players, inform strategies, and deepen fan engagement. Rather than seeking uniformity, baseball celebrates the quirks that make each stadium memorable. Whether it’s a walk-off homer off the Green Monster or a warning-track flyout in a vast center field, the dimensions shape the drama.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?