In the rivers and estuaries of the eastern United States, a quiet but powerful transformation is underway—one driven not by climate shifts or industrial pollution, but by a single, fast-growing fish: the blue catfish (*Ictalurus furcatus*). Originally native to the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio River basins, blue catfish have been introduced far beyond their natural range, particularly into the Chesapeake Bay watershed and its tributaries. While prized by anglers for their size and fight, these apex predators have become a major ecological concern. Their unchecked expansion threatens native species, disrupts food webs, and alters aquatic ecosystems in ways scientists are only beginning to fully understand.

Ecological Impact of Blue Catfish Invasion

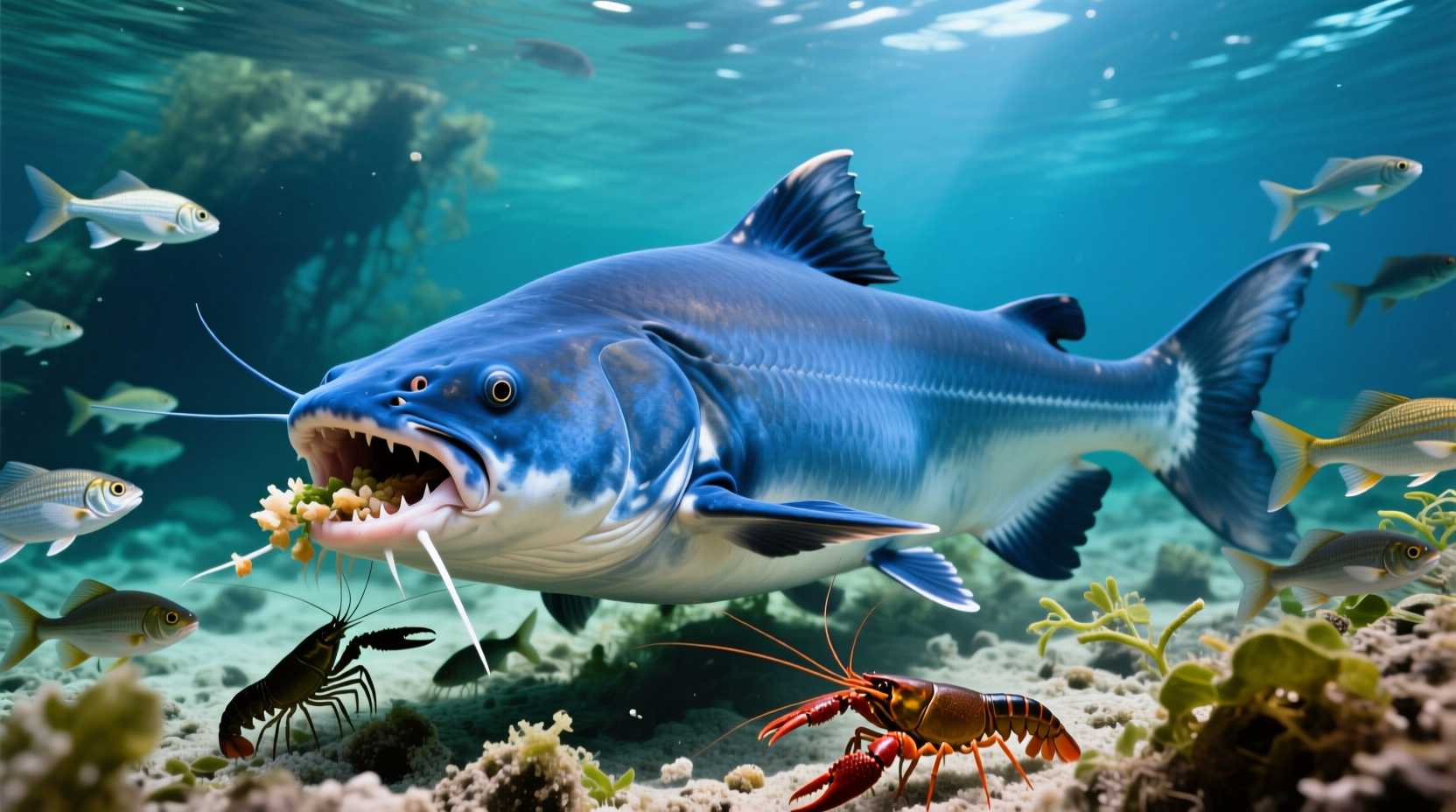

Blue catfish are opportunistic feeders with an enormous appetite. They consume everything from small fish and crustaceans to mollusks and even plant material. In their native habitats, their populations are kept in balance by natural predators and environmental constraints. But in non-native waters—especially in the tidal freshwater and brackish zones of the Potomac, James, and Rappahannock Rivers—they face few natural checks on their growth or reproduction.

Studies show that adult blue catfish can grow over 40 inches long and weigh more than 100 pounds. With lifespans exceeding 20 years, they accumulate significant biomass and dominate their environment. As voracious consumers, they outcompete native predators such as striped bass and white perch for food resources. More alarmingly, they prey directly on ecologically and commercially important species like American shad, river herring, and blue crabs—particularly during juvenile stages when these species are most vulnerable.

Their feeding habits also contribute to trophic cascades. By reducing populations of smaller forage fish, blue catfish indirectly affect birds, larger fish, and even marine mammals that depend on those species. The ripple effect extends through entire food chains, destabilizing ecosystems that have evolved without such a dominant, generalist predator.

How Blue Catfish Spread Beyond Native Range

The expansion of blue catfish into Atlantic coastal rivers began primarily through intentional stocking by state fisheries agencies in the 1970s and 1980s. Virginia and Maryland introduced them to enhance recreational fishing opportunities, assuming their growth would be limited by salinity and temperature. However, researchers later discovered that blue catfish are remarkably adaptable. They thrive in brackish water up to 12 parts per thousand (ppt) salinity—conditions common in the lower Chesapeake Bay—and can migrate dozens of miles upstream to spawn.

Once established, their spread accelerated through natural reproduction and movement. Female blue catfish can produce between 20,000 and 100,000 eggs per spawning event, depending on size and age. Spawning occurs in late spring, with males guarding nests in secluded cavities. Juveniles mature quickly, surviving on plankton and insects before transitioning to larger prey. With no effective biological controls in place, populations exploded—reaching densities of over 5,000 fish per hectare in some areas.

“Blue catfish are not just another game fish. They are ecosystem engineers capable of redefining what’s possible in invaded waters.” — Dr. Mary Fabrizio, Fisheries Ecologist, Virginia Institute of Marine Science

Management Challenges and Control Strategies

Managing invasive blue catfish presents a complex dilemma. On one hand, they support a popular sport fishery and emerging commercial market. On the other, their ecological toll demands intervention. Agencies across the Mid-Atlantic have implemented various strategies, but progress remains slow due to scale, funding, and public perception.

Current approaches include:

- Commercial harvest incentives: State programs encourage fishermen to target blue catfish by removing bag limits and promoting market development.

- Recreational angler engagement: “Eat the Invader” campaigns urge anglers to keep and consume their catch.

- Biological research: Scientists are studying sterilization techniques, migration patterns, and dietary impacts to inform policy.

- Habitat barriers: Some propose using selective fish passage structures to limit upstream spawning migrations.

Despite these efforts, removal rates fall far short of what’s needed to reduce population biomass. One study estimated that harvesting at least 85% of adult fish annually would be required to reverse population trends—a near-impossible threshold given current infrastructure and demand.

Do's and Don'ts for Anglers in Affected Waters

| Action | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Catching a large blue catfish | Do: Keep it if legal; it helps reduce breeding stock. |

| Handling live fish | Don’t: Release large adults back into the water—especially females. |

| Disposing of unused bait | Don’t: Dump live bait; it may introduce other invasives. |

| Reporting unusual catches | Do: Report sightings above historical ranges to state agencies. |

A Closer Look: The Potomac River Case Study

The Potomac River offers a stark example of how rapidly blue catfish can dominate an ecosystem. First documented in the 1980s, the species was rare until the early 2000s. By 2010, surveys revealed that blue catfish made up over 75% of the fish biomass in certain stretches of the tidal river. Scientists analyzing stomach contents found evidence of predation on endangered American eel, juvenile striped bass, and even hatchling turtles.

Local watermen noticed changes too. Crab pots yielded fewer juveniles, and traditional fish like perch became harder to find. While some adapted by targeting blue catfish commercially, others expressed concern about long-term sustainability. The Maryland Department of Natural Resources responded by eliminating creel limits and launching a marketing campaign called “The Blue Catfish Initiative,” aiming to create consumer demand for the meaty, mild-flavored fish.

Still, challenges remain. Processing infrastructure is limited, and consumer awareness lags. Without broader market adoption, removal efforts cannot scale to match reproductive output. The Potomac experience underscores a critical lesson: once an invasive predator becomes established, eradication is rarely feasible—only containment and mitigation are possible.

Step-by-Step: How Communities Can Help Reduce Impact

While large-scale control rests largely with state and federal agencies, individuals and communities play a vital role in slowing the spread and lessening the impact of invasive blue catfish. Here’s how:

- Educate yourself and others: Learn to identify blue catfish versus native species like channel catfish. Share facts with fellow anglers and boaters.

- Harvest responsibly: Follow state guidelines, but lean toward retention—especially for fish over 20 inches, which are likely mature breeders.

- Support sustainable markets: Buy blue catfish from local fisheries or restaurants that source them ethically.

- Prevent accidental spread: Clean boats, trailers, and gear before moving between water bodies to avoid transferring eggs or juveniles.

- Report data: Participate in citizen science programs or report large catches to agencies like the U.S. Geological Survey’s Nonindigenous Aquatic Species database.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are blue catfish dangerous to humans?

No, blue catfish do not pose a direct threat to people. They are not aggressive toward swimmers or boaters. However, their sharp pectoral and dorsal spines can cause painful puncture wounds if handled improperly. Always grasp them firmly behind the head and use gloves when necessary.

Is it safe to eat invasive blue catfish?

Yes, blue catfish are safe and nutritious to eat when sourced from monitored waters. Like all fish, they should be tested for contaminants such as mercury or PCBs, especially in urbanized areas. Many health departments issue consumption advisories—check local guidelines before eating large quantities.

Can blue catfish be eradicated?

Complete eradication is currently not feasible due to their widespread distribution and high reproductive capacity. Instead, management focuses on population suppression, ecosystem monitoring, and preventing further introductions into new watersheds.

Conclusion: A Call to Stewardship

The rise of blue catfish as an invasive species is a cautionary tale of unintended consequences. What began as a well-meaning effort to boost recreation has led to profound ecological disruption. Yet within this challenge lies an opportunity—for collaboration, innovation, and renewed commitment to responsible stewardship of our waterways.

Every angler, chef, policymaker, and citizen has a role to play. Whether it’s choosing to keep your catch, supporting local harvest initiatives, or simply spreading awareness, small actions add up. The health of our rivers and bays depends not just on science and regulation, but on collective responsibility. The time to act is now—before the next generation inherits an ecosystem forever altered.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?