Bryophytes—mosses, liverworts, and hornworts—are among the most ancient land plants, playing a crucial role in the transition from aquatic to terrestrial life. Despite their ecological importance and widespread distribution, one striking feature unites all bryophytes: their diminutive size. Rarely exceeding a few centimeters in height, these plants remain close to the ground in damp, shaded environments. The question arises: why are bryophytes so small? The answer lies not in chance, but in fundamental biological constraints rooted in their anatomy, reproductive strategies, and evolutionary history.

Anatomical Limitations: The Absence of Vascular Tissues

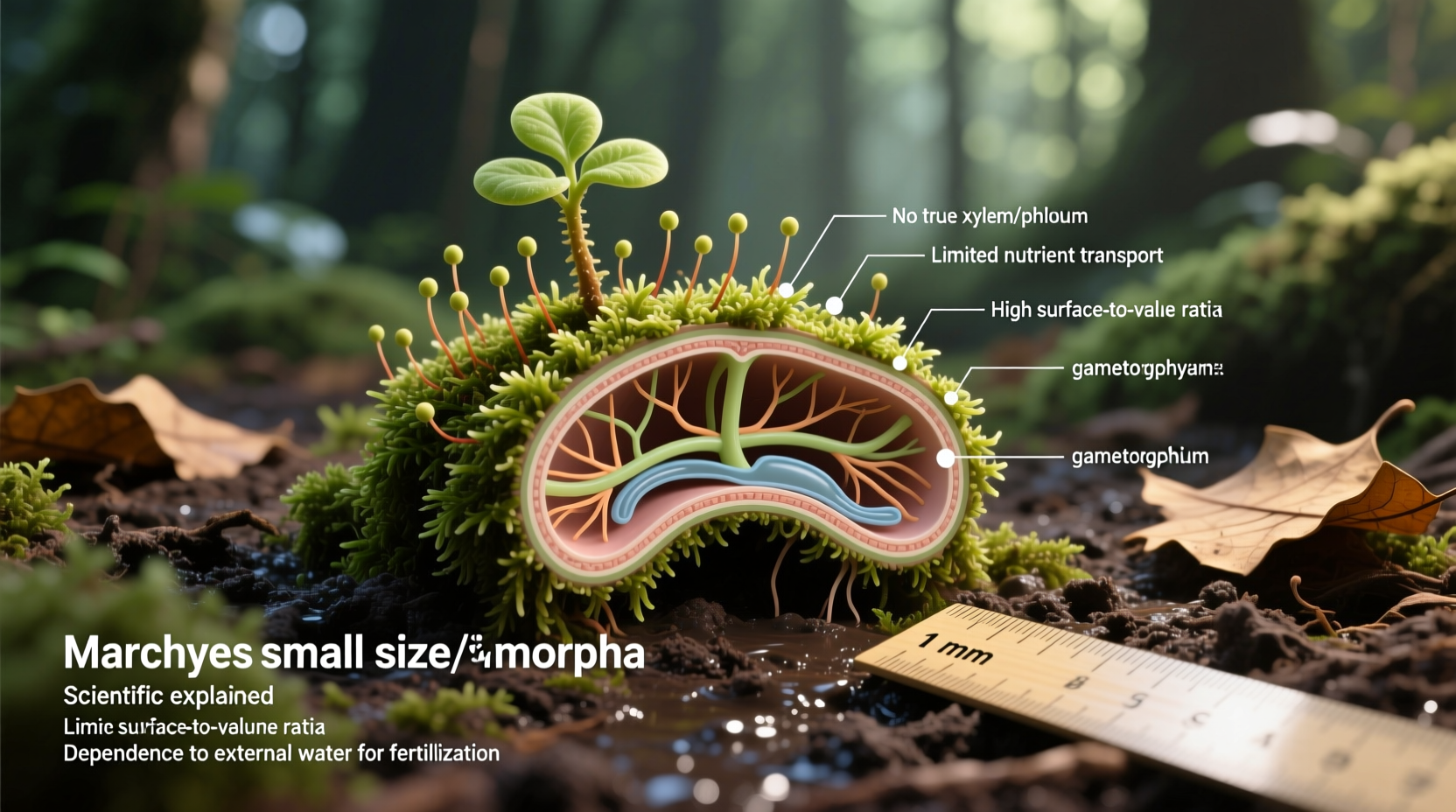

One of the primary reasons bryophytes remain small is the lack of true vascular tissues—xylem and phloem—that are present in more advanced plants like ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms. Vascular tissues enable efficient transport of water, nutrients, and sugars over long distances, allowing taller growth. In contrast, bryophytes rely on diffusion and osmosis for internal transport, which are only effective over short distances.

Without xylem to pull water upward from roots or rhizoids, bryophytes cannot sustain vertical growth beyond a few cell layers. Water must move from cell to cell by passive processes, drastically limiting the height they can achieve. This constraint forces them to grow horizontally or in dense mats, maximizing surface area contact with moisture while minimizing the distance water must travel.

Reproductive Dependence on Water

Bryophytes reproduce via spores and require free water for sexual reproduction. Their sperm cells are flagellated and must swim through a film of water to reach the egg. This dependency restricts fertilization to environments where moisture is consistently available at ground level.

Taller growth would increase the distance between male and female gametangia (antheridia and archegonia), making successful fertilization less likely. By staying small and forming compact colonies, bryophytes ensure that sperm can easily navigate the short path to eggs. This reproductive strategy reinforces their low stature as an adaptive necessity rather than a disadvantage.

“Bryophyte reproduction is elegantly simple but tightly bound to water. Their size is a compromise between survival and reproductive success.” — Dr. Lila Mendez, Plant Evolutionary Biologist

Structural Support and Lack of Lignin

In vascular plants, lignin—a complex polymer—provides rigidity to cell walls, enabling stems to stand upright against gravity. Bryophytes produce little to no lignin, leaving their tissues soft and flexible. While this allows them to survive desiccation and rehydrate when moisture returns, it also means they lack the structural support needed for vertical growth.

Instead of growing tall, bryophytes often form dense carpets or cushions. These structures help retain moisture and protect delicate reproductive organs. The absence of lignified tissues is not a flaw but an adaptation to their niche: colonizing bare soil, rocks, and tree bark where stability matters more than height.

Gas Exchange Without Stomata Regulation

While some bryophytes have primitive stomata-like pores, they lack the sophisticated guard cells found in vascular plants that regulate gas exchange and minimize water loss. As a result, bryophytes are highly susceptible to desiccation. Their small size reduces surface area exposure and allows rapid absorption of water from rain, dew, or fog directly through their leaves and stems.

This direct uptake mechanism works efficiently only in thin, flattened structures. Larger bodies would dry out too quickly or fail to absorb sufficient moisture uniformly. Thus, natural selection has favored compact forms that balance photosynthetic capacity with water retention.

Comparison of Key Traits: Bryophytes vs. Vascular Plants

| Feature | Bryophytes | Vascular Plants |

|---|---|---|

| Vascular Tissue | Absent | Present (xylem & phloem) |

| Lignin Production | Minimal or absent | Abundant in woody tissues |

| Water Transport | Diffusion & osmosis | Capillary action & transpiration pull |

| Fertilization | Requires swimming sperm | Pollen tubes eliminate water need |

| Typical Height | 0.5–5 cm | Several cm to over 100 m |

| Stomatal Control | Limited or none | Well-regulated guard cells |

Ecological Advantages of Small Size

While being small may seem like a limitation, it offers several ecological benefits. Bryophytes are pioneers in disturbed or barren habitats—such as volcanic rock, tundra, or post-fire landscapes—where their low profile protects them from wind and extreme temperatures. Their ability to dry out and revive after rehydration (poikilohydry) makes them resilient in fluctuating conditions.

Moreover, their mat-forming growth stabilizes soil, retains moisture, and creates microhabitats for invertebrates and seedlings of other plants. In boreal forests and cloud forests, mosses contribute significantly to carbon sequestration despite their size. Being small doesn’t mean being insignificant; it means occupying a specialized niche with high efficiency.

Mini Case Study: Sphagnum Moss in Peat Bogs

Sphagnum moss, a dominant bryophyte in northern peatlands, illustrates how small size contributes to large-scale impact. Individual Sphagnum plants rarely exceed 20 cm in height, yet they form extensive, spongy mats up to several meters deep over centuries. Their unique hyaline cells absorb and hold vast amounts of water, acidifying the environment and slowing decomposition.

This slow decay leads to peat accumulation, storing more carbon than any other ecosystem per unit area. Though each plant is tiny, collectively they shape entire ecosystems and influence global climate patterns. Sphagnum’s success lies in its compact, layered growth strategy—proof that size does not determine ecological significance.

Actionable Checklist for Studying Bryophyte Growth

- Observe bryophytes in moist, shaded environments such as forest floors or stream banks.

- Use a hand lens to examine leaf arrangement and rhizoid structures.

- Test water absorption by placing a dry moss sample in water and watching rehydration.

- Compare moss-covered soil moisture to nearby bare ground.

- Sketch a cross-section of a moss stem to visualize cell-to-cell transport.

- Note proximity of male and female structures in dioicous species.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can bryophytes ever grow tall?

No known bryophyte exceeds about 50 cm (e.g., *Dawsonia superba*, a moss), and even this exceptional height relies on internal conducting cells that mimic—but do not equal—true vascular tissue. Most remain under 5 cm due to physiological constraints.

Do bryophytes have roots?

No. Instead, they have rhizoids—thin, hair-like filaments that anchor the plant and absorb water passively. Unlike true roots, rhizoids lack vascular tissue and root caps.

Why don't bryophytes evolve to become larger?

Evolution favors traits that enhance reproductive success in a given environment. For bryophytes, staying small ensures reliable water access, effective gas exchange, and successful fertilization. There’s little selective pressure to grow taller when their current form thrives in their niche.

Conclusion: Embracing the Power of Small

The small size of bryophytes is not a failure of evolution but a refined adaptation to life on land without the complexities of vascular systems. Their simplicity enables resilience, rapid colonization, and outsized ecological contributions. Understanding why bryophytes are small reveals deeper truths about plant evolution: success isn’t measured in height, but in persistence, adaptability, and harmony with environment.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?