At first glance, the microscopic nature of cells might seem like a mere biological coincidence. But the reality is far more intentional: cells are small for critical functional reasons rooted in physics, chemistry, and evolutionary biology. Their diminutive size isn’t arbitrary—it’s a fundamental requirement for survival, efficiency, and effective operation within living organisms. From bacteria to human neurons, the constraints of size govern how cells absorb nutrients, expel waste, communicate, and replicate. Understanding why cells remain small reveals profound insights into the very mechanics of life.

The Surface Area-to-Volume Ratio: The Core Principle

The most important reason cells are small lies in the relationship between surface area and volume. As a cell grows, its volume increases faster than its surface area. This imbalance creates a bottleneck in the cell’s ability to exchange materials with its environment.

Nutrients, oxygen, and signaling molecules must pass through the cell membrane—its surface—to reach the interior. Waste products like carbon dioxide must exit the same way. If a cell becomes too large, the membrane won’t have enough surface area to support the needs of the increased internal volume. Imagine trying to supply an entire city using only a single narrow road—the system would quickly become overwhelmed.

This principle can be illustrated mathematically. A spherical cell with radius r has a surface area of 4πr² and a volume of (4/3)πr³. The surface area-to-volume ratio (SA:V) is therefore proportional to 1/r. As r increases, the ratio decreases. For example:

| Radius (µm) | Surface Area (µm²) | Volume (µm³) | SA:V Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12.57 | 4.19 | 3.00 |

| 5 | 314.16 | 523.60 | 0.60 |

| 10 | 1,256.64 | 4,188.79 | 0.30 |

As shown, doubling the radius reduces the SA:V ratio by half. This means larger cells struggle to sustain metabolic activity because they cannot import resources or export wastes fast enough relative to their internal needs.

Efficient Diffusion and Transport Limitations

Most cellular processes rely on passive diffusion—the movement of molecules from areas of high concentration to low concentration. This process is rapid over short distances but slows dramatically over longer ones. In a small cell, molecules like oxygen or glucose can diffuse from the membrane to the nucleus in milliseconds. In a hypothetical giant cell, diffusion could take minutes or even hours, leading to delays in energy production, protein synthesis, and response to stimuli.

Consider a muscle cell needing ATP during contraction. If it took several seconds for oxygen to diffuse from the membrane to mitochondria deep inside, the cell would fail to respond in time. Evolution has favored small cell sizes to ensure rapid intracellular communication and efficient metabolism.

“Diffusion sets a hard speed limit on cellular logistics. Size matters not just structurally, but temporally.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Cell Biophysicist, MIT

Genetic Control and Protein Production Capacity

Another constraint on cell size is genomic capacity. Most cells contain a single nucleus housing the DNA that directs all protein synthesis. The nucleus produces messenger RNA (mRNA), which travels to ribosomes to make proteins. There is a physical limit to how much mRNA a nucleus can generate at once—and thus, how many proteins can be produced to support cellular functions.

If a cell were to grow excessively large, its cytoplasmic demands (enzymes, structural proteins, transporters) would outpace the nucleus’s ability to supply instructions. This is known as the nucleocytoplasmic ratio. Cells maintain a balance where one nucleus can effectively regulate the surrounding cytoplasm. When this balance is disrupted, function deteriorates.

This explains why some naturally large cells, like bird eggs (e.g., an ostrich egg), are packed with yolk but metabolically inert until fertilization activates gene expression. They are exceptions that prove the rule: without active regulation, large volumes cannot sustain life.

Adaptations That Allow Larger Cells to Function

While most cells are small—typically 1–100 micrometers—some specialized cells defy this norm. Neurons, for instance, can extend over a meter in length. However, they achieve functionality through structural adaptations rather than uniform bulk.

- Neurons have long, thin axons that minimize volume while maximizing reach. Their metabolic machinery is concentrated near the cell body, and materials are transported via motor proteins along microtubules.

- Skeletal muscle fibers are multinucleated, meaning they contain multiple nuclei distributed throughout the cell. This allows localized genetic control across a large volume.

- Plant cells often have large central vacuoles that push organelles toward the periphery, reducing the effective distance for diffusion and maintaining a thin layer of active cytoplasm.

These examples highlight that when evolution permits larger cells, it does so through compensatory mechanisms—not by abandoning the principles that favor small size.

Mini Case Study: The Giant Amoeba Chaos carolinense

A rare exception in the microbial world is *Chaos carolinense*, an amoeba that can grow up to 5 millimeters—visible to the naked eye. Despite its size, it survives due to thousands of nuclei scattered throughout its cytoplasm, each regulating a local region. It also relies on cyclosis, a streaming motion of cytoplasm that actively distributes nutrients instead of waiting for diffusion. This case underscores the rule: even when cells grow large, they evolve workarounds to overcome the limitations of scale.

Step-by-Step: How Cell Size Is Regulated in Nature

Cell size isn’t left to chance. Organisms employ precise regulatory mechanisms to ensure cells divide before becoming inefficient:

- Growth Monitoring: Cells continuously assess their size using sensor proteins that track macromolecule synthesis and membrane expansion.

- Checkpoint Activation: At key points in the cell cycle (e.g., G1/S or G2/M), checkpoints verify whether sufficient growth has occurred—and whether division should proceed.

- DNA Replication Sync: The genome must be duplicated before division. Cells coordinate DNA synthesis with overall size to prevent imbalances.

- Cytokinesis Trigger: Once replication is complete and size thresholds are met, the cell initiates mitosis and splits into two smaller, functional units.

- Feedback Loops: Daughter cells inherit regulatory signals that reset growth programs, ensuring consistent size across generations.

This tight control prevents unchecked growth and maintains optimal SA:V ratios across tissues and species.

Tips for Understanding Cellular Size Constraints

Frequently Asked Questions

Can cells survive if they get too large?

No, beyond a certain size, cells cannot efficiently exchange materials or regulate internal processes. They either divide, die, or develop specialized adaptations like multiple nuclei. Uncontrolled growth, as seen in some cancer cells, often leads to dysfunction and tissue damage.

Why don’t all cells have multiple nuclei to grow larger?

Multiple nuclei increase complexity and energy costs. Most cells prioritize simplicity, rapid division, and tight genetic control. Multinucleation is reserved for specific roles like muscle contraction or nutrient storage, where sustained large size provides functional advantages.

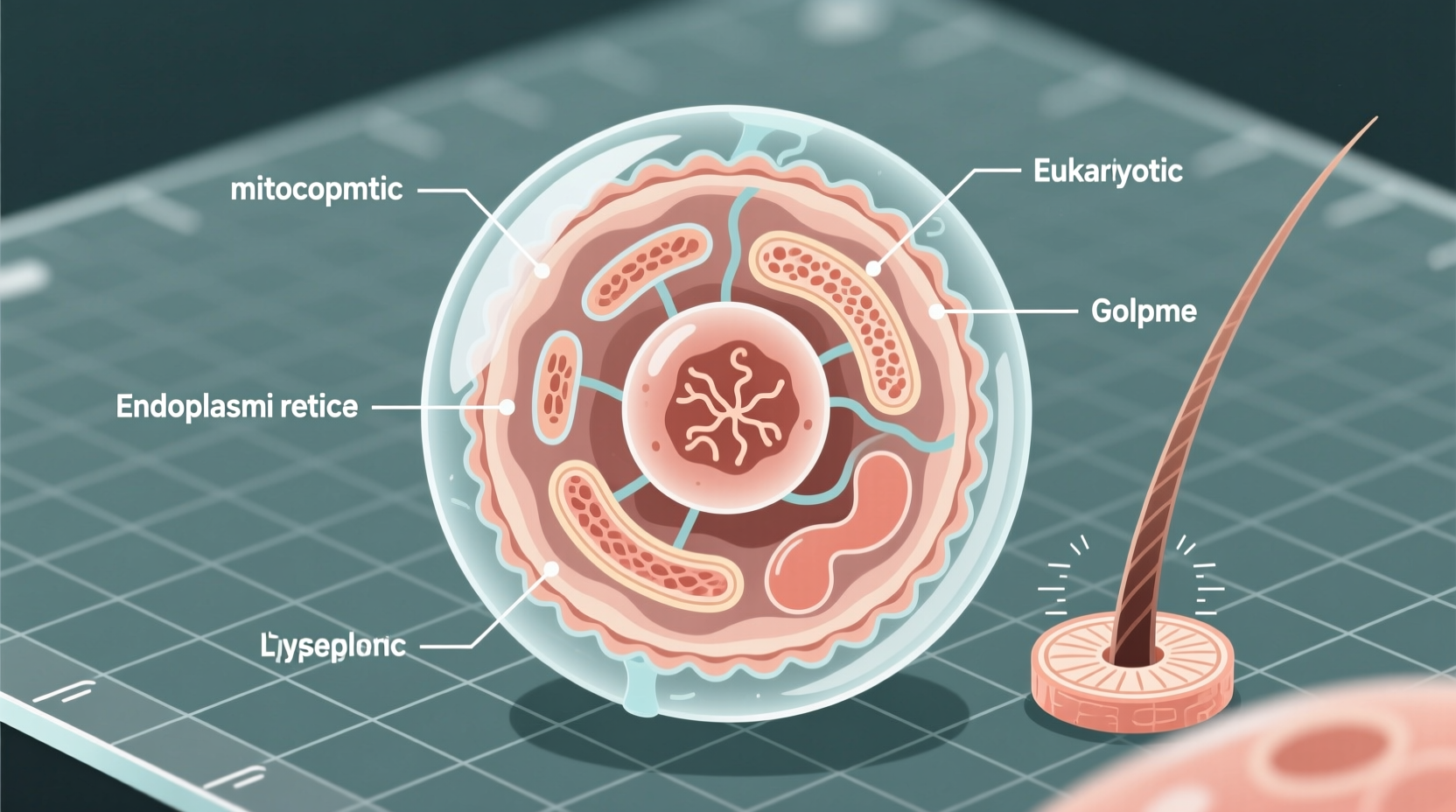

Are prokaryotic cells small for the same reasons as eukaryotic cells?

Yes. Although prokaryotes lack a nucleus, they still rely on diffusion for transport and have high metabolic rates. Their small size (often 1–5 µm) maximizes surface area for nutrient uptake and rapid response to environmental changes.

Checklist: Key Factors Limiting Cell Size

- ✅ High surface area-to-volume ratio for efficient exchange

- ✅ Rapid diffusion of molecules across short distances

- ✅ Effective control by a single nucleus (nucleocytoplasmic ratio)

- ✅ Timely response to environmental signals

- ✅ Energy-efficient maintenance of homeostasis

Conclusion

The small size of cells is not a limitation of evolution but one of its most elegant solutions. By staying tiny, cells ensure efficient nutrient uptake, rapid communication, and precise genetic control—all essential for sustaining life. From the tiniest bacterium to the most complex organ, the principle holds: smaller is smarter when it comes to cellular design. Understanding this fundamental concept opens the door to deeper appreciation of how life operates at its most basic level.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?