Cilia—tiny, hair-like structures extending from the surface of many types of cells—are far more than microscopic curiosities. Though often overlooked, they play critical roles in maintaining human health, enabling sensory perception, facilitating cellular movement, and guiding crucial developmental processes. From clearing mucus in the lungs to determining left-right asymmetry in embryos, cilia operate silently but indispensably across multiple systems in the body. Understanding their functions reveals how deeply interconnected cellular biology is with overall physiological well-being.

The Biological Structure of Cilia

Cilia are slender organelles composed of microtubules arranged in a “9+2” pattern—nine outer microtubule doublets surrounding a central pair. This structure, known as the axoneme, is anchored to the cell by a basal body and powered by motor proteins like dynein, which generate sliding motion between microtubules to produce rhythmic beating or rotational movement.

There are two primary types of cilia: motile and non-motile (also called primary) cilia. Motile cilia are typically found in large numbers on epithelial surfaces such as those lining the respiratory tract and brain ventricles. They beat in coordinated waves to move fluids or particles. In contrast, primary cilia are usually solitary, non-moving antennae that detect mechanical, chemical, or light signals from the environment. Despite their structural differences, both types are essential for normal physiological function.

Respiratory Defense: Clearing Pathogens and Debris

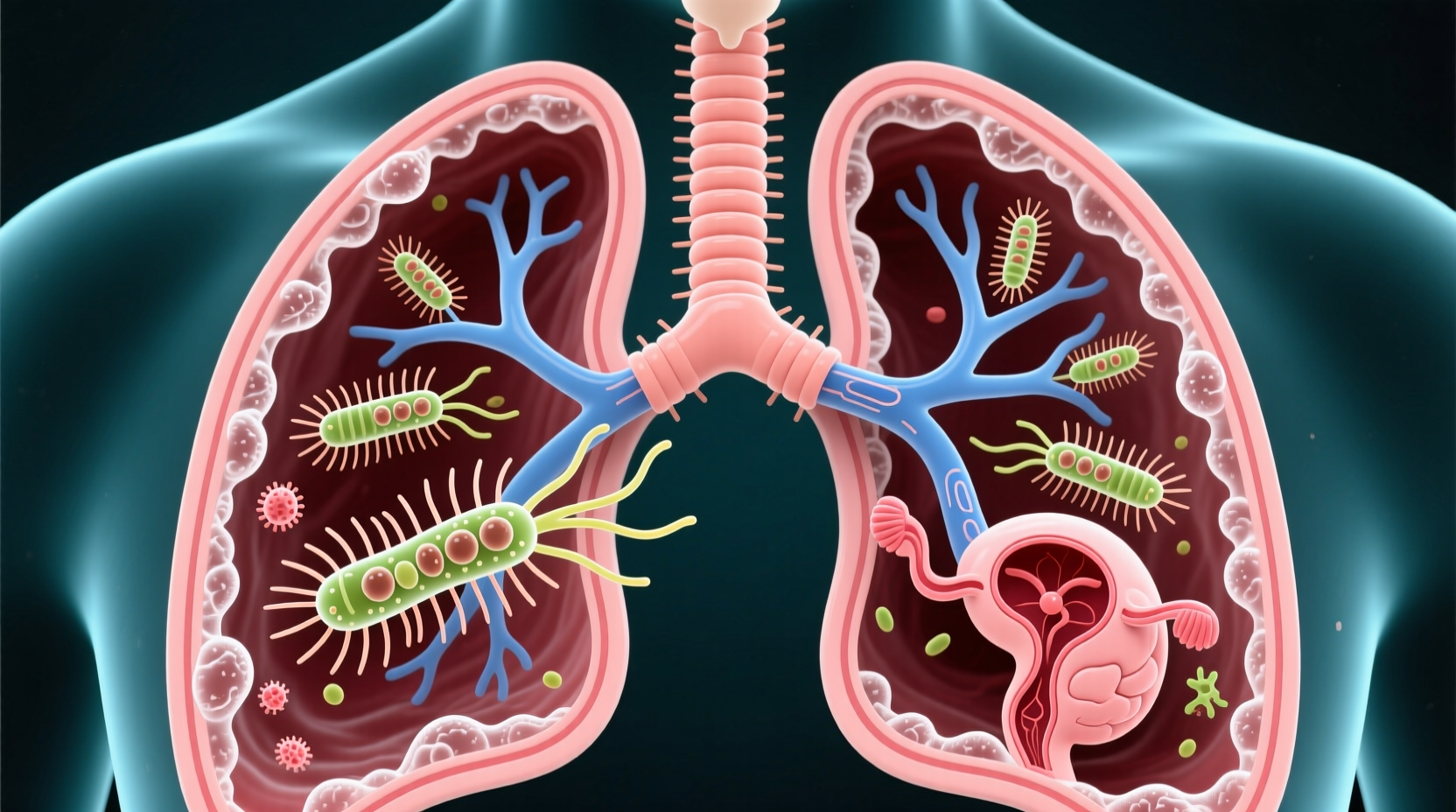

One of the most visible roles of motile cilia occurs in the respiratory system. Lining the trachea, bronchi, and nasal passages, these cilia work in unison to propel mucus upward and out of the airways—a mechanism known as mucociliary clearance. Trapped dust, bacteria, viruses, and allergens are carried toward the throat, where they can be swallowed or expelled.

This self-cleaning system is vital for preventing infections and chronic inflammation. When ciliary function is impaired—due to genetic disorders like primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), smoking, or prolonged exposure to pollutants—mucus accumulates, increasing susceptibility to bronchitis, sinusitis, and pneumonia.

“Cilia are the unsung heroes of lung immunity. Without their constant sweeping action, our airways would quickly become breeding grounds for infection.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Pulmonary Biologist, University of Michigan

Sensory Functions: The Cell’s Antenna

Primary cilia serve as specialized signaling hubs, often referred to as the “cellular antenna.” They house receptors and ion channels that respond to extracellular cues such as hormones, growth factors, and fluid flow. For example, in the kidney tubules, primary cilia bend in response to urine flow, triggering calcium signaling that helps regulate filtration and blood pressure.

In the retina, photoreceptor cells possess modified cilia essential for transporting proteins needed in vision. Defects in these ciliary transport mechanisms contribute to retinal degeneration and blindness. Similarly, olfactory neurons rely on cilia to detect odorants, making them indispensable for the sense of smell.

These sensory roles extend into developmental biology. During embryogenesis, cilia in the node (a small region in early embryos) create directional fluid flow that establishes the left-right axis of the body. Disruption here can lead to situs inversus—a condition where internal organs are mirrored—or more complex organ malformations.

Key Signaling Pathways Regulated by Primary Cilia

| Pathway | Function | Associated Disorders if Impaired |

|---|---|---|

| Hedgehog | Cell differentiation, limb development, neural patterning | Joubert syndrome, basal cell carcinoma |

| Wnt | Tissue regeneration, stem cell regulation | Cystic kidney disease, skeletal defects |

| PDGFRα | Cell migration, fibrosis response | Pulmonary fibrosis, connective tissue disorders |

Motility Beyond the Lungs: Reproduction and Brain Health

Motile cilia also perform critical tasks outside the respiratory tract. In the female reproductive system, ciliated cells in the fallopian tubes help guide the ovum from the ovary to the uterus. Their rhythmic beating facilitates fertilization and proper embryo transport. Reduced ciliary activity may contribute to infertility or ectopic pregnancy.

In the brain, ependymal cells lining the ventricles bear motile cilia that circulate cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This circulation delivers nutrients, removes waste, and maintains intracranial pressure. Disrupted CSF flow due to dysfunctional cilia has been linked to hydrocephalus—an accumulation of fluid in the brain.

Mini Case Study: A Diagnosis Delayed

Sophie, a 7-year-old girl, had suffered recurrent sinus infections, chronic bronchitis, and frequent ear infections since infancy. At age five, she was diagnosed with situs inversus totalis—her heart was on the right side, and her liver on the left. It wasn’t until genetic testing revealed mutations in the DNAH5 gene that doctors confirmed primary ciliary dyskinesia. Her case illustrates how ciliary dysfunction affects multiple systems: impaired mucociliary clearance led to respiratory illness, while defective nodal cilia during embryogenesis caused organ reversal. Early diagnosis allowed for proactive pulmonary care, including daily chest physiotherapy and inhaled therapies, significantly improving her quality of life.

Ciliopathies: When Cilia Fail

Diseases resulting from defective cilia are collectively known as ciliopathies. These genetic disorders underscore just how vital cilia are to human health. Examples include:

- Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD): Caused by mutations affecting primary cilia in renal tubules, leading to uncontrolled cyst formation.

- Bardet-Biedl Syndrome: Characterized by obesity, retinal degeneration, polydactyly, and cognitive impairment—all tied to disrupted ciliary signaling.

- Alström Syndrome: Involves progressive blindness, hearing loss, insulin resistance, and cardiomyopathy due to ciliary defects.

Because cilia are present in nearly every cell type, ciliopathies often affect multiple organs, making diagnosis and treatment complex. Research into these conditions continues to reveal new insights into ciliary biology and potential therapeutic targets.

Checklist: Recognizing Potential Ciliary Dysfunction

- Chronic respiratory infections before age 2

- Recurrent sinusitis or otitis media

- Laterality defects (e.g., heart on the right)

- Unexplained kidney cysts in children

- Progressive vision or hearing loss with other systemic signs

- Developmental delays or polydactyly

Emerging Research and Therapeutic Horizons

Recent advances in molecular biology have elevated cilia from obscure cellular appendages to central players in health and disease. Scientists are now exploring ways to restore ciliary function through gene therapy, small molecule modulators, and targeted drug delivery. For instance, compounds that enhance ciliary beat frequency are being tested for PCD, while Hedgehog pathway agonists show promise in treating certain neurodevelopmental conditions linked to ciliary defects.

Additionally, organoid models derived from patient cells allow researchers to study ciliary behavior in real time, accelerating discovery and personalized medicine approaches. As imaging technologies improve, even dynamic ciliary motion can be visualized at nanoscale resolution, opening new avenues for diagnostics.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can cilia regenerate if damaged?

Yes, most cilia can regrow within hours after injury, provided the basal body remains intact and the cell is healthy. However, chronic damage from toxins like cigarette smoke or persistent infections may impair regrowth and lead to long-term dysfunction.

Are all cells in the body equipped with cilia?

No—not all cells have cilia. Most nucleated cells in mammals possess a single primary cilium during quiescence (G0 phase), but rapidly dividing cells often resorb theirs. Some cell types, like red blood cells or platelets, lack cilia entirely.

How do scientists study cilia?

Researchers use techniques such as immunofluorescence microscopy to label ciliary proteins, high-speed video microscopy to analyze beating patterns, and CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to model ciliopathies in cell lines or animals.

Conclusion: Honoring the Hidden Architects of Health

Cilia are not merely microscopic protrusions—they are dynamic, multifunctional organelles integral to life-sustaining processes. From protecting our lungs to shaping our bodies during development, their influence spans systems and stages of life. As science uncovers more about their roles, it becomes increasingly clear that preserving ciliary health is synonymous with preserving overall wellness.

Whether through avoiding environmental toxins, supporting early diagnosis of ciliopathies, or advancing research into regenerative therapies, we must recognize and protect these silent guardians of cellular function.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?