When driving on a highway, you may have noticed that some curves in the road are tilted inward—higher on the outside and lower on the inside. This design isn’t random or purely aesthetic; it’s a crucial engineering solution rooted in physics. These sloped turns are called \"banked curves,\" and they play a vital role in making travel safer and more efficient. But why exactly are curved roads banked? The answer lies in fundamental principles of motion, force, and gravity.

To understand this, we need to explore how forces act on a vehicle when it rounds a curve, what problems arise on flat surfaces, and how banking solves them. By the end of this article, you’ll grasp the science behind road design—and appreciate the invisible physics that keeps you safe every time you take a turn.

The Problem with Flat Curved Roads

Imagine driving around a sharp corner on a completely flat road. As your car turns, it wants to continue moving in a straight line due to inertia—a concept described by Newton’s First Law of Motion. To change direction, a force must push the car toward the center of the curve. This force is known as centripetal force.

On a flat surface, the only source of this centripetal force is friction between the tires and the road. While friction works under ideal conditions, it has limitations. Wet roads, worn tires, or high speeds can reduce available friction, increasing the risk of skidding outward during a turn.

In short, flat curves place all responsibility for turning on friction—an unreliable ally in adverse conditions. That’s where banking comes in.

How Banking Helps: Redirecting Forces

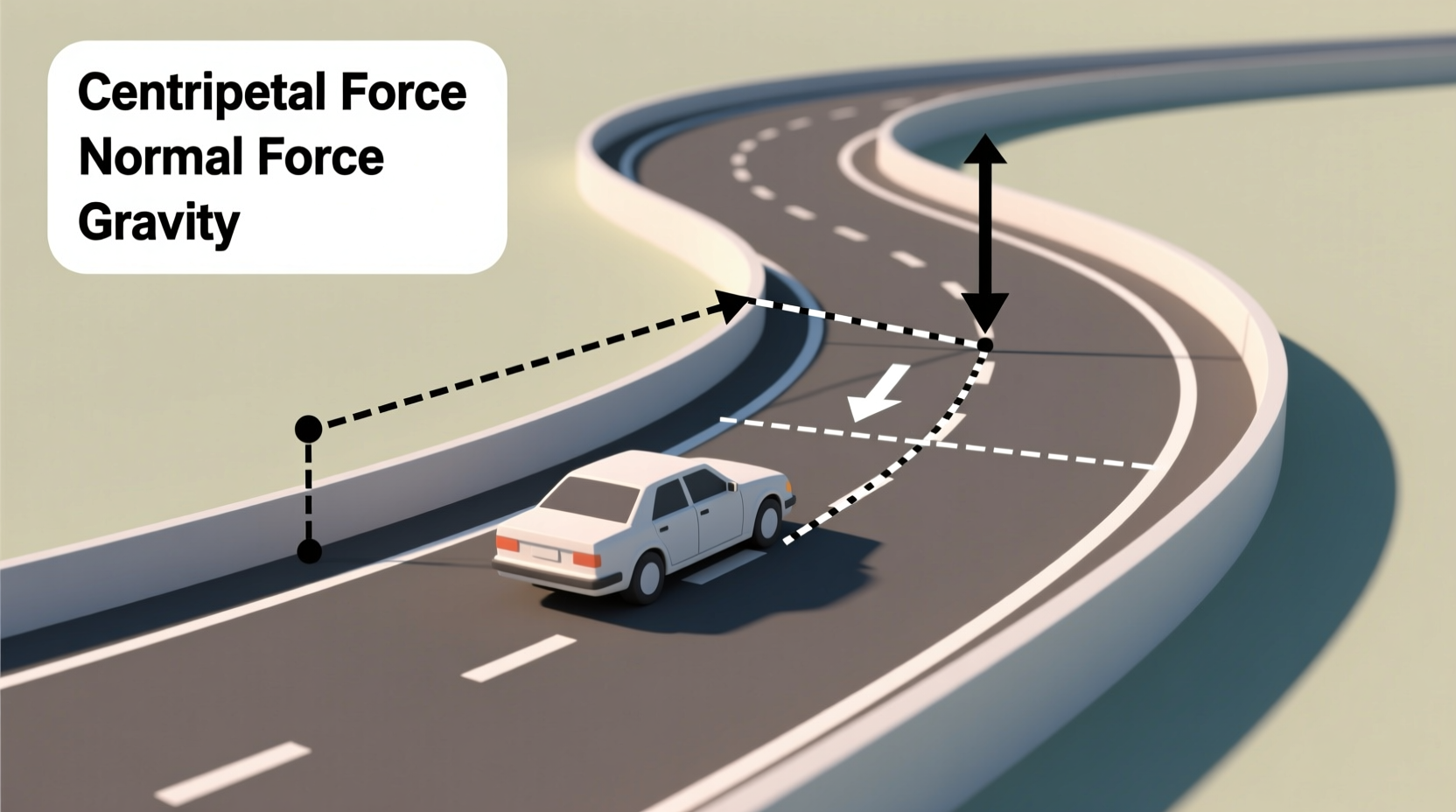

Banking a curve means tilting the road surface so that the outer edge is higher than the inner edge. This tilt changes how forces interact with the vehicle. Instead of relying solely on friction, part of the normal force (the upward push from the road) contributes to the centripetal force needed for turning.

Here’s how it works: Gravity pulls the car downward, while the road pushes up at an angle due to the incline. This upward force—the normal force—is no longer vertical but perpendicular to the slanted surface. Because of the tilt, the normal force now has a horizontal component pointing toward the center of the curve. This component acts as part of the centripetal force, reducing the amount of friction required.

The result? A safer, smoother turn—even without maximum grip. In fact, engineers can calculate the \"ideal banking angle\" where no friction is needed at all, assuming a specific speed and curve radius.

“Banking transforms geometry into safety. It uses basic physics to align natural forces with driver needs.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Civil Engineering Professor

Physics Behind the Perfect Bank Angle

The ideal banking angle depends on two main factors: the speed of the vehicle and the radius of the curve. The formula used by engineers is derived from balancing forces and looks like this:

tan(θ) = v² / (r × g)

- θ = banking angle

- v = velocity of the vehicle (in meters per second)

- r = radius of the curve (in meters)

- g = acceleration due to gravity (~9.8 m/s²)

Let’s break it down with an example. Suppose a highway curve has a radius of 100 meters, and the intended speed is 25 m/s (about 90 km/h or 56 mph). Plugging into the formula:

tan(θ) = (25)² / (100 × 9.8) = 625 / 980 ≈ 0.638

So θ ≈ tan⁻¹(0.638) ≈ 32.5°

This means the road should be banked at roughly 32.5 degrees to allow a vehicle traveling at 90 km/h to navigate the curve safely without depending on friction. Of course, real-world designs include safety margins and account for varying speeds and weather conditions.

Real-World Example: Highway On-Ramps

Consider a common cloverleaf interchange on a freeway. The entrance ramps often form tight curves, yet drivers rarely feel unstable—even when entering at moderate speeds. That’s because these ramps are carefully banked based on expected traffic flow.

In one documented case, transportation engineers in Colorado redesigned a frequently accident-prone on-ramp after multiple winter skids. The original ramp had minimal banking and a small radius. After analysis, they increased the banking angle from 6° to 14° and slightly widened the curve. Over the next year, lateral skid incidents dropped by 78%, proving how effective proper banking can be—even in icy conditions.

This improvement didn’t require new materials or technology—just better application of classical mechanics.

Types of Banking and Their Uses

| Type of Banking | Description | Common Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Zero Banking | No slope; flat surface | Low-speed urban corners |

| Moderate Banking | 5°–12° incline | Highway interchanges, rural roads |

| High Banking | Up to 30°+ incline | Race tracks (e.g., NASCAR ovals) |

| Adaptive Banking | Varies along the curve | Complex mountain roads with changing radii |

Race tracks offer an extreme example: Daytona International Speedway features turns banked at 31 degrees, allowing cars to reach speeds over 320 km/h (200 mph) while maintaining control. Without such banking, those speeds would be impossible—or fatal.

Step-by-Step: How Engineers Design a Banked Curve

- Analyze traffic patterns: Determine average and maximum vehicle speeds using historical data.

- Measure curve radius: Survey the land to establish the tightness of the turn.

- Calculate ideal angle: Apply the tan(θ) = v²/(rg) formula to find optimal banking.

- Add safety margin: Adjust for weather, vehicle types, and human error.

- Test and simulate: Use computer models to predict performance under various conditions.

- Construct and monitor: Build the road and collect post-construction feedback for future improvements.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does banking eliminate the need for friction?

Not entirely. While ideally banked curves can function without friction at a specific \"design speed,\" real-world conditions vary. Vehicles travel faster or slower, roads get wet, and tires wear out. Friction remains essential for safety across diverse scenarios.

Can too much banking be dangerous?

Yes. Excessive banking can cause slow-moving or stopped vehicles to slide inward, especially on icy roads. It can also make drivers feel disoriented. Engineers balance performance with comfort and versatility.

Why aren’t all curves heavily banked?

Cost, terrain, and traffic diversity limit extreme banking. Urban intersections serve pedestrians, bicycles, and delivery trucks—all needing stable, near-flat surfaces. Heavy banking is reserved for high-speed, controlled-access roads.

Key Takeaways and Action Checklist

- Understand that banking reduces dependence on tire friction during turns.

- Recognize that centripetal force comes from both friction and the horizontal component of the normal force on banked roads.

- Respect curve speed signs—they’re calculated based on banking and radius.

- Support infrastructure investments that apply sound physics for public safety.

- Advocate for updated road designs in areas with frequent cornering accidents.

Conclusion: Physics You Can Trust Every Mile

The next time you glide smoothly through a highway curve, remember: you’re experiencing applied physics at its most elegant. Banked roads aren’t just an engineering convenience—they’re a lifesaving application of centuries-old scientific principles. From everyday commutes to high-speed travel, the thoughtful use of angles, forces, and motion keeps millions of drivers safe each day.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?