Flamingos are among the most visually striking birds in the animal kingdom, instantly recognizable by their bright pink feathers, long legs, and curved beaks. But this vivid hue isn’t a genetic default—flamingos aren’t born pink. In fact, newborn flamingos are a dull gray or white. The transformation into that iconic pink occurs gradually and is entirely dependent on what they eat. The reason behind their color lies in a fascinating interplay between biology, chemistry, and ecology.

Their pinkness stems from pigments found in the microorganisms and small aquatic creatures that make up their diet. These compounds, once ingested, are metabolized and deposited into feathers, skin, and even beaks. This article explores the biological mechanisms behind this phenomenon, detailing the role of carotenoids, the digestive process in flamingos, and how environmental factors influence their appearance. We’ll also examine real-world examples, expert insights, and common misconceptions about one of nature’s most colorful adaptations.

The Role of Carotenoids in Flamingo Coloration

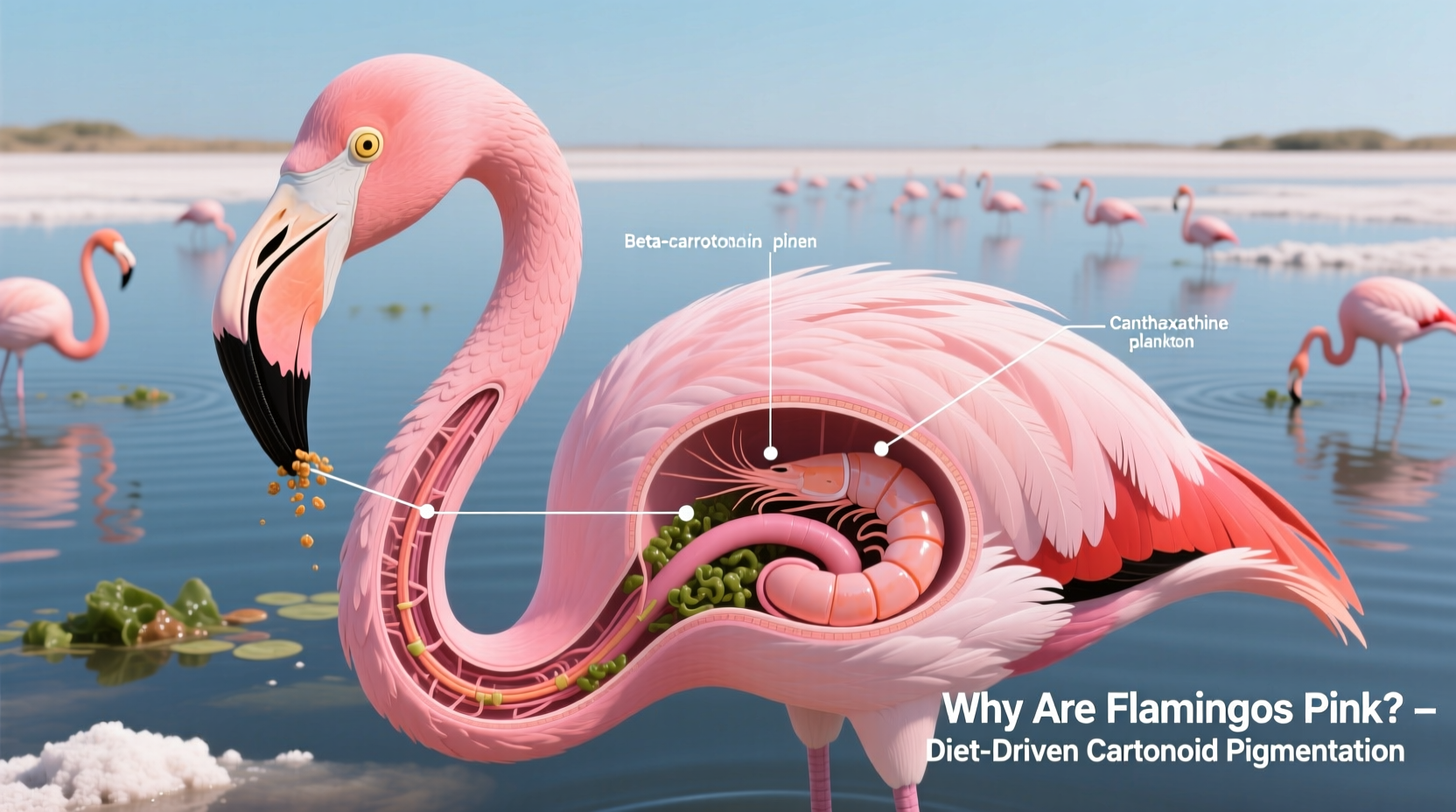

At the heart of the flamingo’s pink coloration are organic pigments called carotenoids. These are naturally occurring compounds synthesized by plants, algae, and certain bacteria. Animals cannot produce carotenoids on their own; they must obtain them through their diet. In flamingos, the primary source of these pigments comes from two key components of their wetland habitat: blue-green algae (such as Spirulina platensis) and brine shrimp (Artemia salina), both rich in carotenoid molecules like beta-carotene and astaxanthin.

Astaxanthin, in particular, plays a dominant role. It is a red-orange pigment commonly found in marine environments and is responsible for the pink color of salmon, lobster, and shrimp as well. When flamingos consume organisms containing astaxanthin, their digestive system breaks down these compounds and transports them via the bloodstream to growing feather follicles. As new feathers grow in, the pigments are incorporated, resulting in the characteristic pink plumage.

Digestive Adaptations That Enable Pigment Absorption

Flamingos possess specialized digestive systems optimized for extracting nutrients—and pigments—from their unusual diet. Their feeding behavior involves filtering large volumes of water using lamellae (comb-like structures) inside their uniquely shaped beaks. As they sweep their heads upside-down through shallow water, they trap algae, diatoms, and tiny crustaceans while expelling excess water and sediment.

Once ingested, the food travels through a complex digestive tract designed to maximize nutrient absorption. Carotenoids are fat-soluble, meaning they dissolve best in lipids. Flamingos have evolved efficient mechanisms to emulsify fats and absorb these pigments in the intestines. Enzymes and bile acids help break down cell walls of algae and shrimp, releasing bound carotenoids for uptake into the bloodstream.

From there, proteins known as lipoproteins transport the pigments to various tissues. Some carotenoids are stored temporarily in the liver, while others are directed to sites of active growth, such as developing feathers during molting cycles. Over time, consistent intake leads to progressive intensification of color.

“Carotenoid-based coloration in flamingos is a direct reflection of dietary quality. It's not just about beauty—it's a biological signal of health and nutritional status.” — Dr. Lena Moretti, Avian Physiologist, University of Cape Town

How Age and Diet Affect Flamingo Color

Chicks hatch without any trace of pink. Their initial gray-white plumage reflects the absence of accumulated carotenoids. Only after weeks or months of feeding on carotenoid-rich foods do juvenile flamingos begin to show faint pink tints. The full vibrancy typically develops over two to three years, coinciding with sexual maturity.

In the wild, the intensity of a flamingo’s color can vary significantly depending on its location. Populations in East Africa’s Lake Natron, where Spirulina-laden waters thrive, tend to display brighter pinks than those in less nutrient-dense lakes. Conversely, flamingos in captivity may lose their color if their diet lacks sufficient carotenoids—a common issue in zoos prior to the understanding of their nutritional needs.

To address this, many modern zoological institutions supplement flamingo diets with natural sources of astaxanthin, such as dried algae, shrimp meal, or even synthetic additives approved for animal consumption. Without these, captive flamingos would gradually fade to pale white or cream tones.

Factors Influencing Flamingo Pigmentation

| Factor | Effect on Color | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Carotenoid Intake | Direct correlation | Higher intake = deeper pink; low intake = paler appearance |

| Water Salinity & Algae Density | Indirect influence | High-salinity lakes support more carotenoid-producing organisms |

| Molting Cycle | Timing of color change | New feathers incorporate pigments only during growth phases |

| Health and Stress Levels | Negative impact when poor | Sick or stressed birds may not absorb pigments efficiently |

| Captive vs. Wild Environment | Variable outcomes | Captivity requires careful diet management to match wild conditions |

Mini Case Study: The Chilean Flamingo at San Diego Zoo

In the early 2000s, caretakers at the San Diego Zoo noticed that their flock of Chilean flamingos (Phoenicopterus chilensis) was losing its vibrant color. Despite appearing healthy, the birds had become noticeably paler over several molting seasons. An investigation revealed that the commercial feed being used, while nutritionally adequate, lacked sufficient levels of natural astaxanthin.

Zoo biologists collaborated with avian nutritionists to reformulate the diet, introducing dried spirulina algae and krill-based supplements. Within six months—and especially after the next molt—the flock regained its rosy glow. Blood tests confirmed higher serum carotenoid levels, and breeding activity increased, suggesting improved overall condition. This case highlighted not only the aesthetic importance of pigmentation but also its link to physiological wellness and reproductive fitness.

Biological Significance of Pink Feathers

Beyond mere appearance, the pink color of flamingos serves an evolutionary purpose. In mate selection, brighter plumage signals better health and stronger immune function. Since carotenoids play roles in antioxidant defense and immune modulation, only individuals capable of acquiring and utilizing large quantities can afford to \"waste\" them on showy feathers. This makes coloration an honest indicator of genetic quality.

During courtship displays, flocks perform synchronized movements where hundreds of birds stretch their necks, flap wings, and parade in unison. Brighter individuals stand out, increasing their chances of attracting a mate. Studies have shown that in controlled settings, flamingos preferentially associate with more colorful partners, reinforcing the selective pressure for intense pigmentation.

- Pink feathers act as a visual cue of foraging success.

- Color intensity correlates with parasite resistance and stress resilience.

- Healthy pigment deposition indicates proper metabolic and digestive function.

Common Misconceptions About Flamingo Color

Despite widespread fascination, several myths persist about why flamingos are pink:

- Myth: Flamingos are genetically programmed to be pink.

Reality: They inherit the ability to metabolize carotenoids, but the color itself depends entirely on diet. - Myth: All species of flamingos are equally pink.

Reality: Species vary in shade—from pale pink (lesser flamingo) to deep rose (greater flamingo)—based on ecological niche and feeding preferences. - Myth: Flamingos turn pink immediately after hatching.

Reality: It takes months to years of feeding to achieve full coloration.

Step-by-Step: How Flamingos Turn Pink Over Time

- Hatching: Chicks emerge with grayish-white down feathers, devoid of pigmentation.

- Early Feeding: Parents feed them crop milk, which contains some carotenoids transferred from their own diet.

- Transition to Solid Food: Juveniles begin filter-feeding on algae and small invertebrates in shallow waters.

- Initial Pigment Deposition: After several weeks, faint pink tinges appear, especially on wing feathers.

- Molting Cycles: Each year, as old feathers are replaced, new ones incorporate more pigments with continued feeding.

- Sexual Maturity: By age 2–3, most flamingos reach peak coloration, signaling readiness to breed.

- Lifetime Maintenance: Continuous intake is required to sustain color; interruption leads to fading.

FAQ

Can flamingos be orange or red instead of pink?

Yes. Depending on the concentration and type of carotenoids consumed, flamingos can range from pale pink to deep red or even orange. Diets high in astaxanthin produce redder tones, while beta-carotene-rich sources lean toward yellow-orange. The final hue is a blend of these pigments.

Do all flamingos turn pink?

All healthy flamingos will develop some degree of pink coloration if their diet includes carotenoids. However, individuals with malnutrition, illness, or limited access to pigmented food sources may remain pale throughout life.

Why don’t other water birds turn pink?

While some birds (like roseate spoonbills) also derive color from carotenoids, flamingos are unique in their specialized feeding mechanism and high intake volume. Their physiology is fine-tuned to extract and utilize large amounts of pigments efficiently, unlike generalist feeders.

Checklist: Key Facts About Flamingo Pigmentation

- ✅ Flamingos get their color from carotenoids in their diet.

- ✅ Primary sources include blue-green algae and brine shrimp.

- ✅ Astaxanthin is the main pigment responsible for pink-red hues.

- ✅ Chicks are born gray and develop color over time.

- ✅ Captive flamingos need supplemented diets to stay colorful.

- ✅ Brighter color indicates better health and fitness.

- ✅ Molting is necessary for new pigmented feathers to appear.

Conclusion

The pink color of flamingos is far more than a quirk of nature—it’s a living testament to the intricate connections between diet, biochemistry, and evolution. Their vibrant feathers are essentially a visible record of what they’ve eaten, how well they’ve absorbed nutrients, and how effectively their bodies allocate resources. From the alkaline lakes of Africa to zoo enclosures around the world, the story of the flamingo’s pinkness underscores a fundamental truth: appearance in the animal kingdom is rarely superficial.

Understanding this phenomenon enriches our appreciation of wildlife and reminds us that even the most dazzling traits often have humble, earthly origins. Whether you're observing them in the wild or at a sanctuary, take a moment to consider the journey behind that blush of pink—it’s written in algae, filtered through beaks, and etched into feathers by biology itself.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?