The halogens—fluorine, chlorine, bromine, iodine, and astatine—are among the most reactive elements in the periodic table. Found in Group 17, these nonmetals play crucial roles in industrial chemistry, biological systems, and everyday products like disinfectants and pharmaceuticals. But what makes them so eager to react? The answer lies deep within their atomic structure and electron behavior. Understanding halogen reactivity isn't just academic—it explains everything from why table salt forms so easily to how water is sanitized.

Atomic Structure and the Drive for Stability

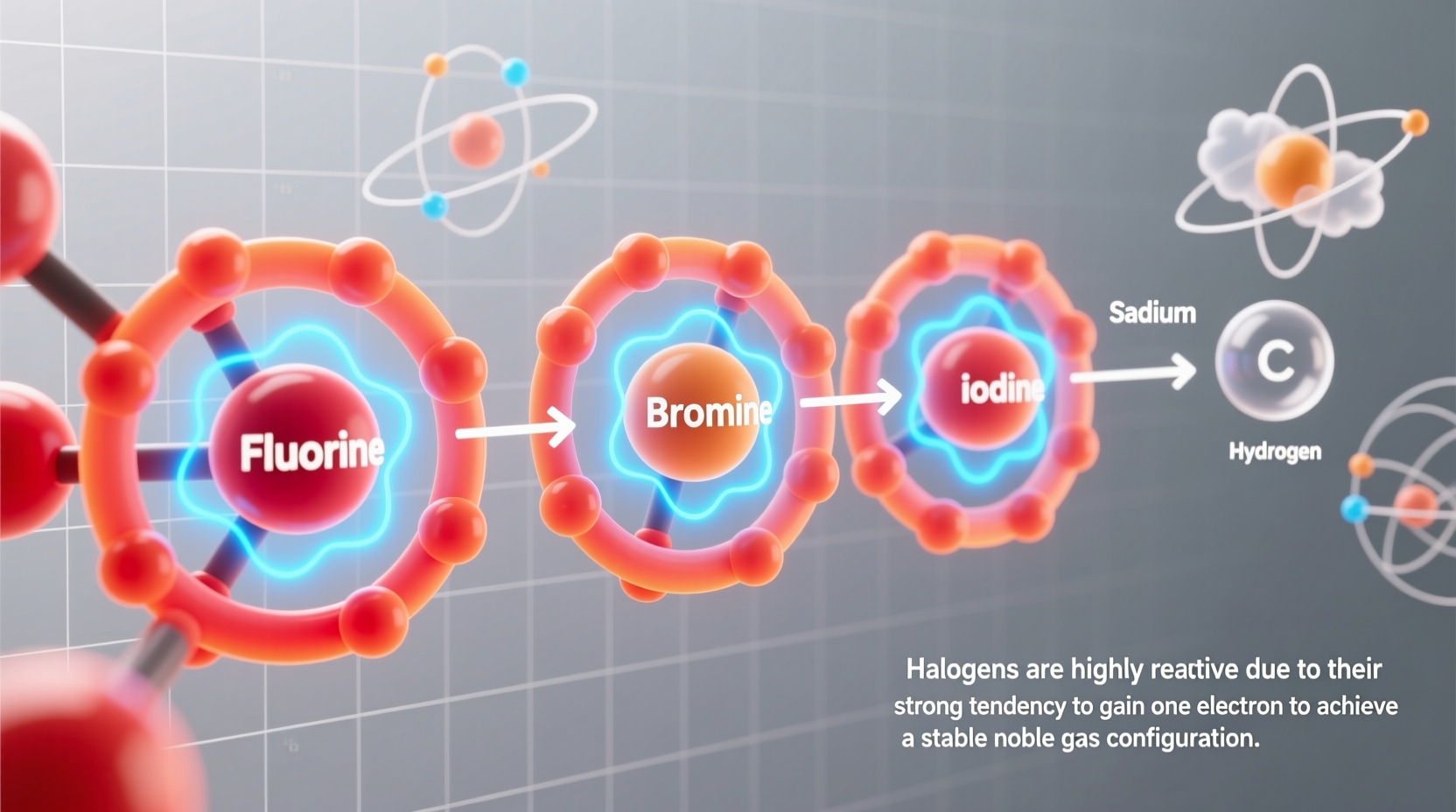

All halogens share a similar outer electron configuration: seven valence electrons. This means they are just one electron short of achieving a stable, full outer shell—a state known as the octet rule. Atoms strive for stability, and the easiest path for halogens is to gain that single missing electron through chemical bonding.

This electron hunger creates a powerful driving force behind their high reactivity. Unlike metals, which tend to lose electrons, halogens act as oxidizing agents—they aggressively pull electrons from other atoms. Fluorine, at the top of the group, is the most electronegative element on the periodic table, meaning it has the strongest pull on electrons. As you move down the group, electronegativity decreases, but the fundamental desire to complete the valence shell remains.

Electronegativity and Reactivity Trends

Electronegativity is a key factor in explaining why halogens react so readily. It measures an atom’s ability to attract electrons in a bond. Fluorine tops the Pauling scale with a value of 3.98, making it the most electronegative element. This intense electron-pulling power allows fluorine to form strong bonds and react violently with many substances—even water and glass under certain conditions.

As we descend the group—from fluorine to chlorine, bromine, and iodine—atomic size increases. The larger the atom, the farther the valence electrons are from the nucleus, reducing the effective nuclear charge felt by incoming electrons. Consequently, electronegativity drops. This trend directly affects reactivity: fluorine > chlorine > bromine > iodine.

“Fluorine doesn’t just participate in reactions—it often dominates them. Its reactivity is so extreme that chemists must use specialized equipment to handle it safely.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Inorganic Chemistry Researcher, MIT

Comparing Halogen Reactivity: A Practical Overview

To better understand how reactivity changes across the group, consider their behavior in displacement reactions. When a more reactive halogen is added to a solution containing a less reactive halide ion, it displaces the weaker halogen. For example:

- Chlorine gas bubbled into potassium bromide solution produces bromine and potassium chloride.

- Iodine cannot displace chlorine from sodium chloride—demonstrating its lower reactivity.

This pattern confirms the reactivity order and illustrates practical applications in qualitative analysis and purification processes.

| Halogen | State at Room Temp | Electronegativity (Pauling) | Reactivity Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorine (F₂) | Pale yellow gas | 3.98 | Extremely High |

| Chlorine (Cl₂) | Greenish-yellow gas | 3.16 | High |

| Bromine (Br₂) | Red-brown liquid | 2.96 | Moderate |

| Iodine (I₂) | Shiny gray solid | 2.66 | Low |

| Astatine (At) | Radioactive solid | ~2.2 | Very Low (theoretical) |

The physical states also reflect intermolecular forces increasing with molecular size. While fluorine and chlorine are gases, bromine is a volatile liquid, and iodine sublimes slowly—each step indicating stronger London dispersion forces but reduced chemical reactivity.

Real-World Example: Water Disinfection with Chlorine

A practical illustration of halogen reactivity is chlorine’s use in drinking water treatment. When Cl₂ dissolves in water, it undergoes hydrolysis:

Cl₂ + H₂O → HCl + HOCl

The resulting hypochlorous acid (HOCl) is a potent oxidizing agent that destroys bacteria and viruses by disrupting cell membranes and damaging vital proteins. This reaction leverages chlorine’s intermediate reactivity—strong enough to kill pathogens, but controllable enough for safe public use. Over time, however, excess chlorine can react with organic matter to form potentially harmful byproducts like trihalomethanes, illustrating the balance required in applied chemistry.

In contrast, fluorine would be too reactive for such controlled environments, while iodine lacks sufficient potency for rapid disinfection. Thus, chlorine occupies a \"Goldilocks zone\" of reactivity for this critical application.

Step-by-Step: How Halogens React with Metals

The formation of metal halides demonstrates halogen reactivity in a straightforward sequence:

- Contact: A halogen molecule (e.g., Cl₂) approaches a reactive metal like sodium (Na).

- Electron Transfer: Sodium donates its single valence electron to chlorine, forming Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions.

- Bond Formation: The oppositely charged ions attract, creating an ionic compound—sodium chloride (NaCl).

- Energy Release: The reaction is highly exothermic, often producing visible light or heat.

- Stability Achieved: Both elements reach stable electron configurations—sodium achieves a noble gas configuration, and chlorine completes its octet.

This process occurs rapidly with alkali metals and less vigorously with transition metals, depending on ionization energy and lattice stability. The same principle applies across the group, though reaction intensity diminishes with heavier halogens.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why doesn’t iodine react as strongly as fluorine?

Iodine has a larger atomic radius and lower electronegativity than fluorine. Its valence electrons are farther from the nucleus and less tightly held, making it harder to attract additional electrons. Additionally, iodine forms weaker bonds due to poorer orbital overlap, reducing its overall reactivity.

Can halogens exist freely in nature?

No, halogens are rarely found in their elemental form in nature because of their high reactivity. Instead, they occur as halide ions (e.g., Cl⁻, Br⁻) in minerals and salts. For instance, sodium chloride (table salt) is abundant in seawater and underground deposits.

Is astatine reactive like other halogens?

Theoretically, yes—but astatine is extremely rare and radioactive, with a half-life of less than a minute for most isotopes. Due to its instability and scarcity, experimental data on its reactivity is limited. Predictions suggest it behaves similarly to iodine but with even lower reactivity.

Practical Checklist for Handling Reactive Halogens

For students, researchers, or industry professionals working with halogens, safety and precision are essential. Follow this checklist when dealing with halogen reactions:

- ✅ Use fume hoods when handling gaseous halogens like chlorine or fluorine.

- ✅ Wear appropriate PPE: gloves, goggles, and lab coats resistant to chemical exposure.

- ✅ Store halogens in sealed, labeled containers away from flammable materials.

- ✅ Never mix halogens with ammonia or organic solvents without proper protocols.

- ✅ Have neutralizing agents (e.g., sodium thiosulfate) available for spills.

- ✅ Review MSDS (Material Safety Data Sheets) before any experiment involving halogens.

Conclusion: Harnessing Reactivity Responsibly

The reactivity of halogens stems from a simple yet powerful principle: the pursuit of electron stability. Their seven-valence-electron configuration drives them to seize electrons from other elements, leading to vigorous and often useful chemical transformations. From life-saving disinfectants to essential components in pharmaceuticals and polymers, halogens shape modern science and industry.

Understanding *why* they react—the interplay of electronegativity, atomic size, and electron affinity—empowers safer handling, smarter applications, and deeper appreciation of chemical behavior. Whether you're a student mastering periodic trends or a professional designing new compounds, recognizing the roots of halogen reactivity opens doors to innovation and control in the chemical world.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?