Americans spend more on healthcare per capita than any other developed nation—yet health outcomes often lag behind. The average family premium for employer-sponsored insurance exceeds $23,000 annually, and medical bills remain a leading cause of personal bankruptcy. Behind these staggering numbers lie systemic issues that inflate costs at every level. Understanding the root causes is essential for informed decision-making, policy advocacy, and personal financial planning.

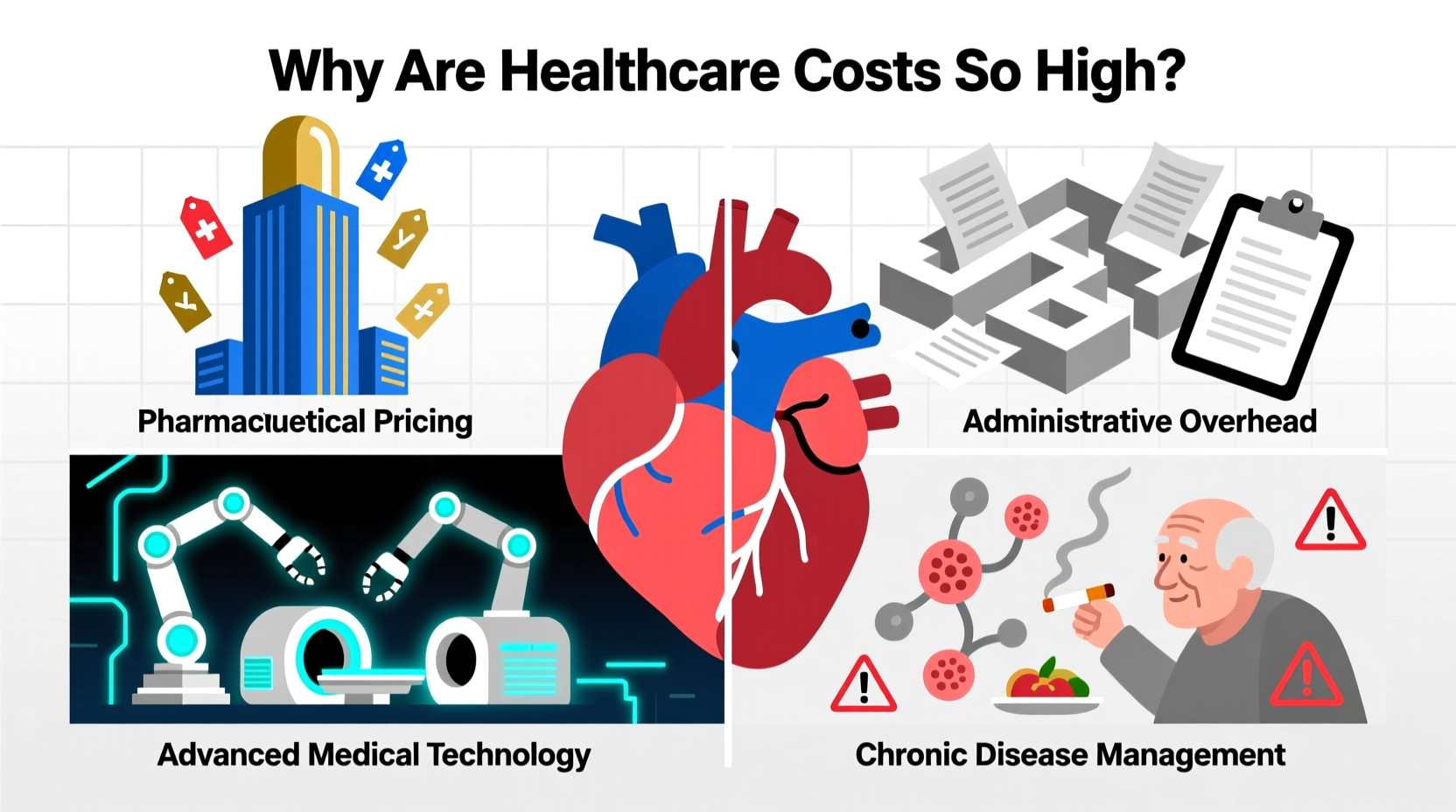

1. Administrative Complexity and Overhead

The U.S. healthcare system operates through a fragmented network of private insurers, public programs, hospitals, and providers—all using different billing codes, claims processes, and reimbursement rules. This lack of standardization creates massive administrative overhead. Studies estimate that administrative costs account for nearly 15–30% of total U.S. healthcare spending, far exceeding rates in countries with single-payer or simplified systems.

Hospitals and clinics employ entire departments to manage insurance authorizations, coding disputes, and patient billing. Physicians spend an average of two hours on paperwork for every hour spent with patients. These inefficiencies don’t improve care—they increase costs passed directly to consumers.

2. High Prices for Medical Services and Pharmaceuticals

One of the most direct drivers of high healthcare costs is the price tag attached to services and drugs. In the U.S., procedures like MRIs, CT scans, and joint replacements cost significantly more than in peer nations—even after adjusting for income and inflation.

For example, a knee replacement averages $31,000 in the U.S., compared to $17,000 in Germany and $10,000 in Canada. Similarly, prescription drug prices are largely unregulated, allowing pharmaceutical companies to set high initial prices. Insulin, a life-saving medication available for decades, can cost over $300 per vial in the U.S., while retailing for less than $30 in many other countries.

“Drug pricing in the U.S. isn’t based on value or production cost—it’s based on what the market will bear.” — Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School

The absence of centralized price negotiation gives insurers limited leverage, especially when only one manufacturer produces a critical drug. Patent extensions, \"pay-for-delay\" deals, and limited generic competition further entrench high prices.

3. Technology and Overutilization of Care

While medical innovation has saved countless lives, it also contributes to rising costs. New technologies—such as robotic surgery systems, advanced imaging, and gene therapies—often come with premium price tags. Hospitals invest heavily in cutting-edge equipment not only for clinical benefit but also for marketing advantage, creating a cycle of capital expenditure that must be recouped through higher service fees.

Moreover, the fee-for-service model incentivizes volume over value. Providers are paid per test, procedure, or visit rather than for patient outcomes. This encourages overtesting and overtreatment. A study by the Journal of the American Medical Association estimated that up to 25% of imaging tests provide no meaningful clinical benefit.

| Procedure | U.S. Average Cost | Canada Average Cost | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRI (Brain) | $1,100 | $450 | +144% |

| Cesarean Section | $22,600 | $7,100 | +218% |

| Colonoscopy | $3,000 | $600 | +400% |

This disparity reflects not just higher prices, but also greater utilization. The U.S. performs more imaging studies and specialist visits per capita than most OECD countries, often without better health results.

4. Chronic Disease and Preventable Illness

Over half of American adults live with at least one chronic condition—diabetes, heart disease, obesity, or hypertension. These conditions require ongoing management, frequent hospitalizations, and expensive medications. Treating chronic illness accounts for about 90% of the nation’s $4.3 trillion annual healthcare expenditure.

Yet many of these diseases are preventable through lifestyle changes, early screening, and community-based interventions. However, the U.S. spends disproportionately on treatment rather than prevention. Public health funding remains low, and access to nutrition education, fitness programs, and mental health services is inconsistent.

Consider diabetes: a person with diagnosed diabetes incurs average annual medical expenditures of over $16,000—more than twice that of someone without the disease. But research shows that structured lifestyle intervention programs can reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by up to 58% in high-risk individuals.

5. Insurance Design and Patient Financial Burden

Even with insurance, patients face rising out-of-pocket costs. High-deductible health plans (HDHPs) have become increasingly common, shifting financial responsibility onto consumers. In 2023, the average deductible for an individual HDHP exceeded $1,500—with some plans requiring $3,000 or more before coverage kicks in.

These designs can backfire: patients delay or skip necessary care due to cost concerns, leading to worsened conditions and higher long-term expenses. A Commonwealth Fund survey found that 43% of working-age adults skipped care because of cost—rates far higher than in other industrialized nations.

“We’ve created a system where people are insured but still afraid to use their benefits.” — Sara Collins, Vice President for Health Care Coverage and Access, The Commonwealth Fund

Additionally, surprise billing—unexpected charges from out-of-network providers during emergencies—remains a problem despite recent federal protections. While the No Surprises Act reduced some instances, loopholes persist, particularly in air ambulance services and lab testing.

Mini Case Study: The Emergency Room Visit That Cost $8,000

Jennifer, a 42-year-old teacher with employer insurance, visited an in-network hospital ER for severe abdominal pain. After tests, she was diagnosed with kidney stones and discharged with medication. Her insurer covered most of the facility fee, but she received a separate $5,200 bill from an out-of-network radiologist who read her CT scan. Despite appealing, she remained liable for $3,800. This case illustrates how fragmented provider networks and opaque billing practices expose even insured patients to financial risk.

Actionable Checklist: Reducing Your Personal Healthcare Costs

- Compare prices for non-emergency procedures using tools like Healthcare Bluebook or Fair Health Consumer.

- Ask for itemized bills and review them for errors or duplicate charges.

- Use in-network providers and confirm all specialists involved are covered under your plan.

- Negotiate cash prices—many facilities offer discounts for upfront payment.

- Utilize preventive services fully covered under ACA-compliant plans (e.g., vaccines, cancer screenings).

- Enroll in patient assistance programs for high-cost medications offered by manufacturers or nonprofits.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why doesn’t the U.S. government regulate healthcare prices like other countries?

The U.S. historically resists centralized price controls, favoring market competition. However, the lack of regulation allows providers and drugmakers to set prices based on demand rather than cost. Recent legislation allows Medicare to negotiate certain drug prices starting in 2026—a shift toward controlled pricing, though limited in scope.

Does better technology justify higher U.S. healthcare spending?

While the U.S. leads in medical innovation, spending more does not consistently yield better outcomes. Life expectancy is lower, and maternal mortality is higher than in comparable nations. Much of the spending goes toward administrative waste, inflated prices, and overuse—not superior care.

Can switching to a different insurance plan lower my costs?

Possibly. During open enrollment, compare plans not just by premiums but by total expected cost—consider deductibles, copays, and pharmacy coverage. A slightly higher premium might save thousands if you anticipate frequent care.

Conclusion: Taking Control in a Broken System

The reasons behind high healthcare costs are deeply embedded in policy, economics, and industry structure. While systemic reform is slow, individuals can take practical steps to navigate the system more wisely. From questioning bills to prioritizing prevention, every action helps reduce personal financial strain and promotes smarter use of resources.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?