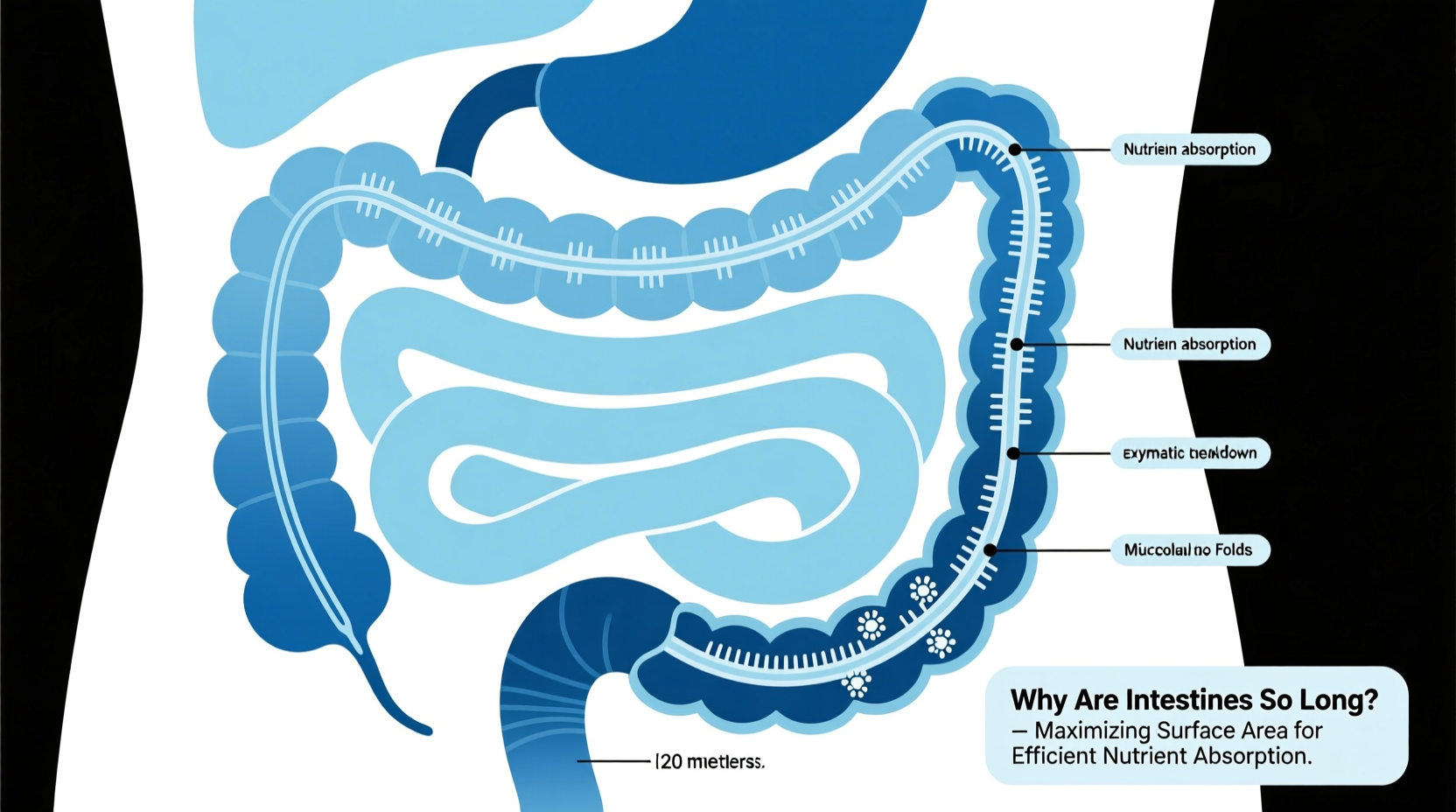

The human digestive system is a marvel of biological engineering, with each organ playing a precise role in breaking down food and extracting essential nutrients. Among these organs, the intestines stand out—not just for their function, but for their surprising length. Stretching over 20 feet in an average adult, the intestines occupy a significant portion of the abdominal cavity. But why are they so long? The answer lies in evolutionary adaptation, physiological necessity, and the intricate demands of efficient digestion.

This extended structure isn't arbitrary; it's a finely tuned mechanism that maximizes surface area, prolongs transit time, and ensures thorough nutrient absorption. Understanding the purpose behind intestinal length reveals how deeply form follows function in human biology.

The Anatomy of the Intestines: A Two-Part System

The intestines consist of two main sections: the small intestine and the large intestine. Though they work as a continuous unit, each has distinct roles shaped by its structural design.

- Small Intestine: Approximately 20 feet (6 meters) long, this is where most nutrient absorption occurs. It’s divided into three parts: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.

- Large Intestine: About 5 feet (1.5 meters) long, responsible primarily for water absorption and waste formation. It includes the cecum, colon, rectum, and anal canal.

Despite being called \"small,\" the small intestine is longer than the large intestine—but narrower in diameter. This elongated, coiled structure allows it to fit within the confined space of the abdomen while maintaining extensive surface area.

Why Length Matters: Surface Area and Absorption Efficiency

The primary reason for the intestines’ extraordinary length is to increase surface area. Greater surface area means more space for villi and microvilli—tiny finger-like projections lining the small intestine—to absorb nutrients from digested food.

To put this into perspective, the total absorptive surface of the small intestine is roughly 30 times larger than the external surface area of the human body. This amplification is achieved through three levels of structural folding:

- Circular folds (plicae circulares): Permanent ridges in the intestinal wall.

- Villi: Finger-like projections extending into the lumen.

- Microvilli: Microscopic bristles on epithelial cells, forming the \"brush border.\"

Without sufficient length, these structures couldn’t provide enough cumulative surface area to meet the body’s nutritional demands. Evolution favored longer intestines in omnivorous and herbivorous species because plant-based diets require more time and surface area to break down complex carbohydrates and extract limited nutrients.

“Intestinal length is directly correlated with dietary complexity. Species that consume fibrous plants tend to have proportionally longer intestines than carnivores.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Gastrointestinal Biologist

Digestive Transit Time: Slowing Down for Maximum Benefit

Another critical function of intestinal length is regulating the speed at which food moves through the digestive tract. Efficient digestion requires time—time for enzymes to act, for nutrients to diffuse across membranes, and for symbiotic bacteria to assist in fermentation.

In the small intestine, transit typically takes 2–6 hours. The large intestine may retain material for another 10–59 hours, depending on diet and individual physiology. This controlled pace prevents rapid expulsion of undigested food and supports optimal nutrient uptake.

Shorter intestines, like those seen in strict carnivores such as cats, reflect a high-protein, easily digestible diet that doesn’t require prolonged processing. Humans, however, evolved to thrive on diverse foods—including fiber-rich plants—necessitating a longer, slower digestive pathway.

Comparative Digestive Transit Times Across Species

| Species | Intestinal Length (approx.) | Primary Diet | Transit Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 25 feet | Omnivore | 24–72 hours |

| Cow | 120 feet | Herbivore | 60–70 hours |

| Dog | 15 feet | Scavenger/Carnivore | 8–10 hours |

| Rabbit | 10 feet (relative to size) | Herbivore | 12–24 hours |

The data shows a clear trend: herbivores and omnivores possess longer intestines relative to body size, enabling them to extract energy from tough plant matter. Humans fall in between, reflecting our evolutionary flexibility in diet.

Adaptations That Enhance Function Along the Length

Length alone isn’t enough—the intestines employ several physiological adaptations along their entire span to maintain efficiency:

- Peristalsis: Rhythmic muscle contractions that move food forward in a controlled manner.

- Segmentation: Localized contractions that mix chyme (partially digested food) with enzymes and increase contact with the intestinal wall.

- Gut microbiota: Trillions of beneficial bacteria residing primarily in the large intestine, aiding in fermentation of indigestible fibers and synthesis of vitamins like B12 and K.

- Mucus secretion: Protects the lining and facilitates smooth passage of waste.

These mechanisms work synergistically across the full length of the intestines, turning passive tubing into a dynamic biochemical processing plant.

Mini Case Study: Digestive Challenges in Short Bowel Syndrome

Consider the case of Maria, a 42-year-old woman who underwent surgical removal of nearly half her small intestine due to Crohn’s disease complications. Post-surgery, she struggled with chronic diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue—classic symptoms of malabsorption.

Her condition, known as short bowel syndrome (SBS), illustrates what happens when intestinal length is compromised. Without sufficient absorptive surface, even a nutritious diet failed to sustain her. She required intravenous nutrition initially and later transitioned to oral rehydration solutions and specialized low-residue meals.

Maria’s experience underscores the vital role of intestinal length: it’s not just about volume, but sustained exposure to digestive processes. Her medical team emphasized slow eating, frequent small meals, and hydration—strategies aimed at compensating for reduced functional capacity.

Practical Tips for Supporting Intestinal Health

While you can’t change your anatomy, you can support your intestines’ natural functions through lifestyle choices. Here are actionable steps to promote healthy digestion and maximize the efficiency of your existing intestinal length:

- Eat fiber-rich foods like vegetables, legumes, and whole grains to support motility and feed beneficial gut bacteria.

- Stay hydrated—water is essential for softening stool and aiding nutrient transport.

- Avoid excessive processed foods and sugars, which can disrupt microbial balance.

- Engage in regular physical activity to stimulate peristalsis.

- Manage stress through mindfulness or breathing exercises, as the gut-brain axis influences digestive function.

Checklist: Daily Habits for Optimal Gut Function

- ✅ Drink at least 8 glasses of water

- ✅ Consume 25–30g of dietary fiber

- ✅ Eat slowly and chew food well

- ✅ Include fermented foods (e.g., yogurt, kimchi)

- ✅ Move your body for 30 minutes

Frequently Asked Questions

Can intestinal length change during a person’s lifetime?

No, the physical length of the intestines remains constant after development. However, functional length can be affected by surgery (e.g., resection), inflammation, or diseases like Crohn’s, which may reduce effective absorption.

Do taller people have longer intestines?

Generally, yes. Intestinal length correlates with height and body size. Taller individuals tend to have slightly longer digestive tracts, though the proportional relationship remains consistent across adults.

Why don’t we feel discomfort from having so much tissue packed inside?

The intestines are highly flexible and suspended by a membrane called the mesentery, allowing movement and expansion. Smooth muscle control and neural feedback prevent over-distension under normal conditions.

Conclusion: Respecting the Design of Your Digestive System

The remarkable length of the human intestines is no accident—it’s the result of millions of years of evolution shaping a system capable of extracting maximum value from varied diets. From microscopic villi to rhythmic contractions, every feature supports a single goal: sustaining life through efficient digestion and absorption.

Understanding why intestines are so long empowers you to make better choices about what you eat and how you live. By honoring this intricate system with proper nutrition, hydration, and care, you allow it to perform at its best.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?