Ladybugs—those small, spotted beetles often found on leaves or sunlit windowsills—are among the most recognizable insects in the world. Their bright orange shells seem to glow against green foliage, making them stand out rather than blend in. This raises a compelling question: why are ladybugs orange? More than just an aesthetic trait, their vivid coloring is a sophisticated evolutionary strategy tied to survival, defense, and communication. Beyond the familiar orange form, ladybugs also appear in red, yellow, black, and even brown, each variation serving a biological purpose. Understanding these colors offers insight into predator-prey dynamics, warning signals in nature, and the delicate balance of adaptation.

The Evolutionary Purpose of Bright Colors

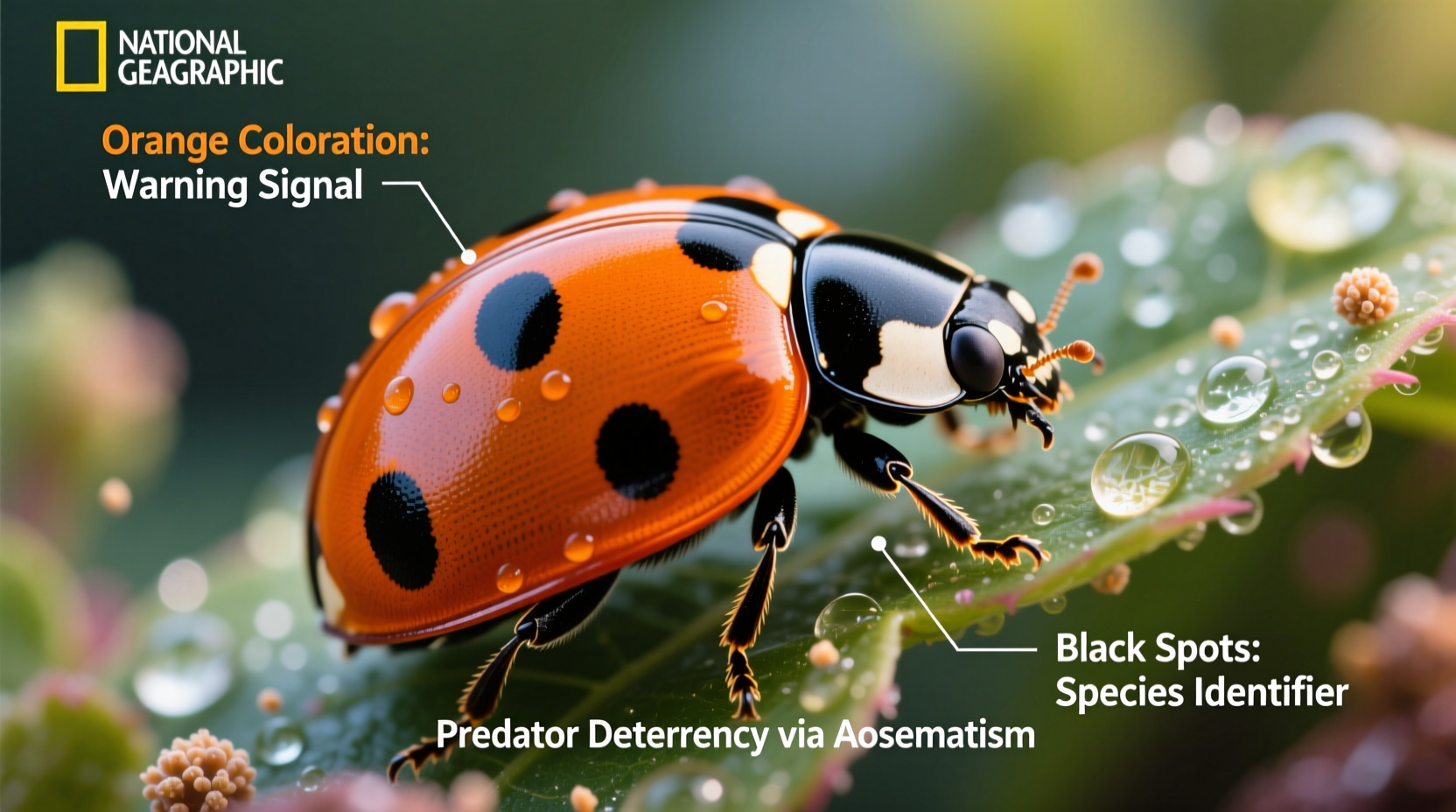

In nature, standing out can be dangerous. Most animals rely on camouflage to avoid predators, but ladybugs do the opposite—they advertise their presence with bold hues. This phenomenon is known as aposematism: the use of bright colors to warn potential predators of toxicity or unpalatability. Ladybugs produce toxic alkaloids in their bodies, particularly when threatened, which make them distasteful or even harmful to birds, lizards, and other insectivores. The orange (or red) shell acts as a billboard: “I don’t taste good—don’t eat me.”

Studies have shown that birds quickly learn to associate bright colors with bad experiences. In controlled experiments, avian predators that tried eating brightly colored ladybugs avoided similar-looking insects afterward, even if those insects were harmless mimics. This learned avoidance reinforces the effectiveness of the warning system across generations.

Color Variations Across Species and Environments

While the classic seven-spotted ladybug (*Coccinella septempunctata*) is bright red-orange, not all ladybugs conform to this standard. Over 6,000 species exist worldwide, displaying a wide range of colors and patterns. Some common variations include:

- Red-orange: Most common; highly visible in temperate regions.

- Yellow or cream: Found in milder climates; may indicate lower toxin levels.

- Black with red spots: Seen in species like the pine ladybird (*Exochomus quadripustulatus*), often in forested areas.

- All-black or dark brown: Rare, but present in certain high-altitude or shaded habitat species.

These differences aren't random. They reflect adaptations to local environments, predator types, and microclimatic conditions. For example, darker ladybugs absorb more heat, giving them an advantage in cooler regions. Lighter-colored ones may be less conspicuous in sandy or dry landscapes where bright orange would be too stark.

“Color in ladybugs isn’t just for show—it’s a finely tuned communication system shaped by millions of years of evolution.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Entomologist at the University of California, Davis

Do Color and Pattern Predict Toxicity?

Research suggests a correlation between color intensity and chemical defense. A study published in *Behavioral Ecology* found that ladybugs with brighter elytra (wing covers) contained higher concentrations of defensive alkaloids. Predators consistently avoided these individuals after initial negative encounters.

Interestingly, spot patterns also play a role. The number, size, and contrast of spots influence how easily predators recognize and remember the insect. High-contrast patterns—like black spots on a bright background—are processed faster by bird brains, accelerating the learning process.

| Color Variation | Common Habitat | Potential Defense Level | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bright Orange/Red | Gardens, fields, urban areas | High | Most effective warning signal |

| Light Yellow | Dry grasslands, coastal zones | Moderate | Less deterrent effect observed |

| Black with Red Spots | Coniferous forests | Medium-High | Thermoregulatory advantage |

| Dark Brown/Black | Shaded woodlands, mountainous regions | Variable | Rare; may rely more on crypsis |

Threats to Ladybugs Despite Their Defenses

Even with their chemical armor and visual warnings, ladybugs face growing threats. One of the most significant is the invasive Harmonia axyridis, or harlequin ladybug, introduced globally for pest control. While effective at consuming aphids, this species outcompetes native ladybugs, sometimes preying on them directly. Unlike many natives, *H. axyridis* exhibits extreme color polymorphism—from pale yellow to deep red—and can overwhelm local ecosystems due to its rapid reproduction and aggression.

Habitat loss, pesticide use, and climate change further stress native populations. As temperatures rise, some species shift ranges, disrupting established predator-prey relationships. In areas where birds haven’t learned to avoid certain colors, newly arrived bright ladybugs may suffer higher predation until the signal becomes recognized.

Mini Case Study: The Decline of the Two-Spotted Ladybug

In the northeastern United States, the native two-spotted ladybug (*Adalia bipunctata*) was once abundant. Over the past three decades, sightings have plummeted. Researchers from Cornell University linked this decline directly to the spread of *Harmonia axyridis*. Field observations showed that while both species share similar orange-red coloring, the invasive type produces stronger defensive chemicals and reproduces faster. Native ladybugs, despite their warning colors, couldn’t compete. This case illustrates that even effective evolutionary strategies can fail under intense ecological pressure.

How to Support Healthy Ladybug Populations

Gardeners and nature enthusiasts can play a role in preserving native ladybugs. These beneficial insects help control aphid and mite populations naturally, reducing the need for chemical pesticides. Supporting biodiversity means creating habitats where native species can thrive without being overtaken by invasives.

📋 **Action Checklist for Supporting Ladybugs**- Avoid broad-spectrum pesticides that harm beneficial insects.

- Plant diverse native flowers like yarrow, dill, and fennel to attract ladybugs.

- Provide overwintering sites such as leaf litter or undisturbed garden corners.

- Refrain from releasing non-native ladybugs (e.g., purchased *H. axyridis*) for pest control.

- Report unusual ladybug sightings to local entomology programs or citizen science databases.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are all orange ladybugs poisonous?

No, ladybugs aren’t technically “poisonous” in the way venomous snakes are. However, they are distasteful and mildly toxic due to defensive chemicals released from their leg joints when threatened. These compounds deter predators but pose little risk to humans, though rare allergic reactions can occur.

Why do some ladybugs have no spots?

Spot count varies by species and doesn’t always correlate with age or gender. Some species, like *Cycloneda sanguinea*, naturally lack distinct spots. Others may have fused or faded markings. The primary function of spots is visual signaling—not individual identification.

Can ladybugs change color?

Not dynamically like octopuses, but their appearance can shift slightly. After molting, young ladybugs may appear paler before their exoskeleton hardens and pigments stabilize. Environmental factors like diet and temperature during development can also influence final color intensity.

Conclusion: Nature’s Warning System in Action

The orange hue of ladybugs is far more than a charming detail—it’s a masterclass in evolutionary design. From deterring predators with honest signals to adapting coloration across climates, these tiny beetles exemplify how survival shapes appearance. Yet, their brilliance cannot shield them from human-driven threats like invasive species and habitat fragmentation. Recognizing the meaning behind their colors fosters deeper appreciation and encourages conservation-minded choices in our gardens and communities.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?