Lobsters are among the most visually striking creatures of the sea, especially when served on a plate bright red after being plunged into boiling water. Yet in their natural habitat, they appear dark blue-green or even mottled brown. This dramatic color change has fascinated diners and scientists alike for decades. The transformation isn’t magic—it’s chemistry. Behind this vivid shift lies a fascinating interplay of proteins, pigments, and heat that reveals how marine biology adapts to environmental conditions. Understanding why lobsters turn red when cooked offers more than dinner trivia; it uncovers fundamental principles of biochemistry at work in nature.

The Natural Color of Live Lobsters

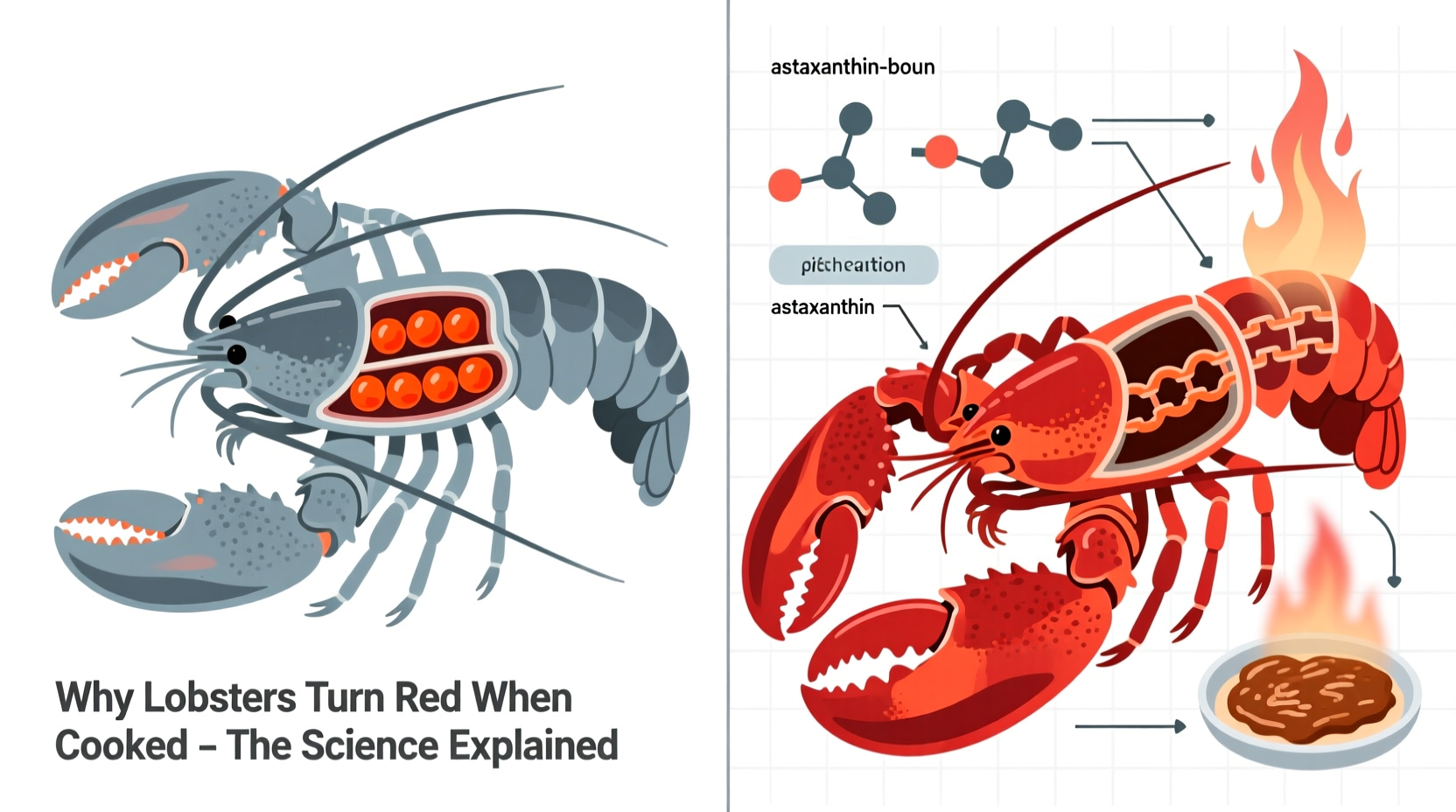

In the wild, Atlantic lobsters (Homarus americanus) typically display a dark, camouflaging hue ranging from olive green to deep blue or reddish-brown. This complex coloring helps them blend into rocky ocean floors, avoiding predators such as seals, octopuses, and large fish. Their shell contains a mixture of pigments, but one compound dominates: astaxanthin.

Astaxanthin is a carotenoid pigment—related to those found in carrots and tomatoes—and is responsible for the pink-red tones seen in many marine animals, including salmon, shrimp, and flamingos. However, in live lobsters, astaxanthin doesn't appear red. Instead, it's bound to a protein called crustacyanin, which alters its molecular structure and shifts its light absorption properties. This binding causes the pigment to reflect blue-green wavelengths rather than red ones.

“Carotenoids like astaxanthin are not just about color—they play roles in antioxidant defense and immune function in marine species.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Marine Biochemist, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

How Heat Changes the Chemistry of Color

When a lobster is exposed to high temperatures during cooking, the crustacyanin protein begins to denature—meaning its three-dimensional structure unravels due to thermal energy. As the protein unfolds, it releases the astaxanthin molecules it was holding. Once freed, astaxanthin reverts to its natural chemical configuration, which absorbs light differently and reflects a vibrant red-orange color.

This process is irreversible. Even if cooled, the protein cannot refold properly without biological machinery (like chaperone proteins), so the red color remains permanent. It's a classic example of a heat-induced conformational change in biochemistry—one that produces an instantly recognizable visual signal.

Why Don’t All Crustaceans Turn Red?

While lobsters are the most famous example, other crustaceans—including crabs, crayfish, and shrimp—also contain astaxanthin and undergo similar color changes when cooked. However, the final shade varies based on species-specific pigment ratios and shell composition.

For instance, some crabs have higher concentrations of yellow carotenoids alongside astaxanthin, resulting in an orange or golden-red finish. Cooked shrimp often appear pink because they contain less total pigment and thinner shells that transmit light differently.

| Species | Live Color | Cooked Color | Primary Pigment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic Lobster | Olive-green to blue-brown | Bright red | Astaxanthin + Crustacyanin |

| Dungeness Crab | Purple-brown | Red-orange | Astaxanthin with minor carotenoids |

| Whiteleg Shrimp | Translucent gray-green | Pink | Low-concentration astaxanthin |

| Crayfish | Dark green-brown | Orange-red | Astaxanthin bound to crustacyanin |

Rare Color Variants and Genetic Exceptions

Naturally occurring colored lobsters—such as bright blue, calico, or even albino individuals—are rare but well-documented. A blue lobster, for example, results from a genetic mutation causing overproduction of crustacyanin, which binds more astaxanthin and enhances the blue tone. Even these unusual specimens turn red when cooked, because heat still breaks down the protein-pigment complex.

True albino lobsters, lacking all pigmentation, remain white both before and after cooking. These occur roughly once in every 100 million lobsters. Similarly, “split” lobsters—half male, half female with different coloring on each side—are the result of gynandromorphism, a rare developmental anomaly. Regardless of initial appearance, cooking will always reveal the underlying presence (or absence) of astaxanthin.

Mini Case Study: The Blue Lobster That Went Red

In 2021, a Maine fisherman pulled a vivid cobalt-blue lobster from his trap. Weighing two pounds, it drew local media attention and was donated to a marine education center. Staff initially believed it might retain its color when cooked—but after a controlled demonstration using a small claw sample, they observed the same transformation: within seconds of boiling, the blue turned deep red. DNA testing later confirmed a harmless mutation in the gene regulating crustacyanin expression. The full lobster was preserved uncooked for public display, serving as a living lesson in marine genetics and biochemistry.

Step-by-Step: What Happens When You Boil a Lobster

- Raw State: Astaxanthin is bound to crustacyanin in the exoskeleton, producing a dark, camouflaged shell.

- Heat Application: As water temperature rises (typically above 60°C / 140°F), proteins begin to destabilize.

- Protein Denaturation: Crustacyanin loses its folded shape, breaking its bond with astaxanthin.

- Pigment Release: Free astaxanthin molecules return to their stable red form.

- Color Fixation: The red color becomes locked in place as the shell hardens under heat.

- Cooling: Even after cooling, the red remains because the protein cannot spontaneously refold.

FAQ: Common Questions About Lobster Color

Do all lobsters turn exactly the same shade of red?

No. While most become a bright crimson, the exact tone depends on the individual’s diet, age, and species. Lobsters fed more krill or algae rich in carotenoids tend to develop richer reds. Water chemistry (such as mineral content) can also subtly affect the final color.

If astaxanthin is red, why don’t lobsters just stay red all the time?

Because camouflage is essential for survival. A naturally red lobster would be highly visible against dark seabeds. By masking astaxanthin with crustacyanin, evolution provided a protective disguise while retaining access to the pigment’s health benefits.

Can you tell if a lobster is fresh by its cooked color?

Not definitively. While a uniform, vibrant red suggests proper cooking, discoloration (like black spots or pale patches) may indicate spoilage, enzyme activity, or incomplete cooking. Always rely on smell and texture as better freshness indicators.

Practical Checklist for Home Cooks

- ✔ Source live lobsters whenever possible for optimal texture and safety.

- ✔ Use a large pot with plenty of salted water (similar to seawater salinity).

- ✔ Bring water to a rolling boil before adding the lobster.

- ✔ Cook for approximately 8–12 minutes per pound.

- ✔ Look for the shell to turn uniformly bright red as a sign of doneness.

- ✔ Avoid overcooking to preserve both color vibrancy and meat tenderness.

- ✔ Store leftovers promptly in the refrigerator and consume within two days.

Conclusion: More Than Just a Dinner Transformation

The reason lobsters turn red when cooked is a perfect intersection of biology, chemistry, and evolution. Far from being a mere culinary curiosity, this phenomenon illustrates how organisms manipulate light and molecules for survival. The hidden red pigment, masked by protein complexity, only emerges under extreme conditions—revealing nature’s quiet brilliance in unexpected ways.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?