Microplastics—tiny plastic particles less than 5 millimeters in size—are now ubiquitous in our environment. From deep ocean trenches to mountain air, they have infiltrated ecosystems and human bodies alike. Once considered a distant byproduct of industrial waste, microplastics are now recognized as a pressing global health and ecological threat. Their persistence, ability to travel across vast distances, and capacity to carry toxic substances make them far more dangerous than previously assumed. Understanding the scope of this issue is essential for making informed choices and advocating for systemic change.

What Are Microplastics and Where Do They Come From?

Microplastics fall into two main categories: primary and secondary. Primary microplastics are intentionally manufactured at small sizes, such as microbeads in cosmetics, synthetic fibers from clothing, or plastic pellets used in industrial production. Secondary microplastics result from the breakdown of larger plastic items—bottles, bags, fishing nets—due to sunlight, wind, and wave action over time.

Everyday activities contribute significantly to microplastic pollution. Washing synthetic clothes releases thousands of microfibers per load into wastewater. Tire wear on roads generates microscopic rubber particles that wash into rivers. Even the peeling of paint from buildings contributes to airborne microplastics. These particles are so lightweight that they can travel through air and water, spreading contamination far beyond their origin.

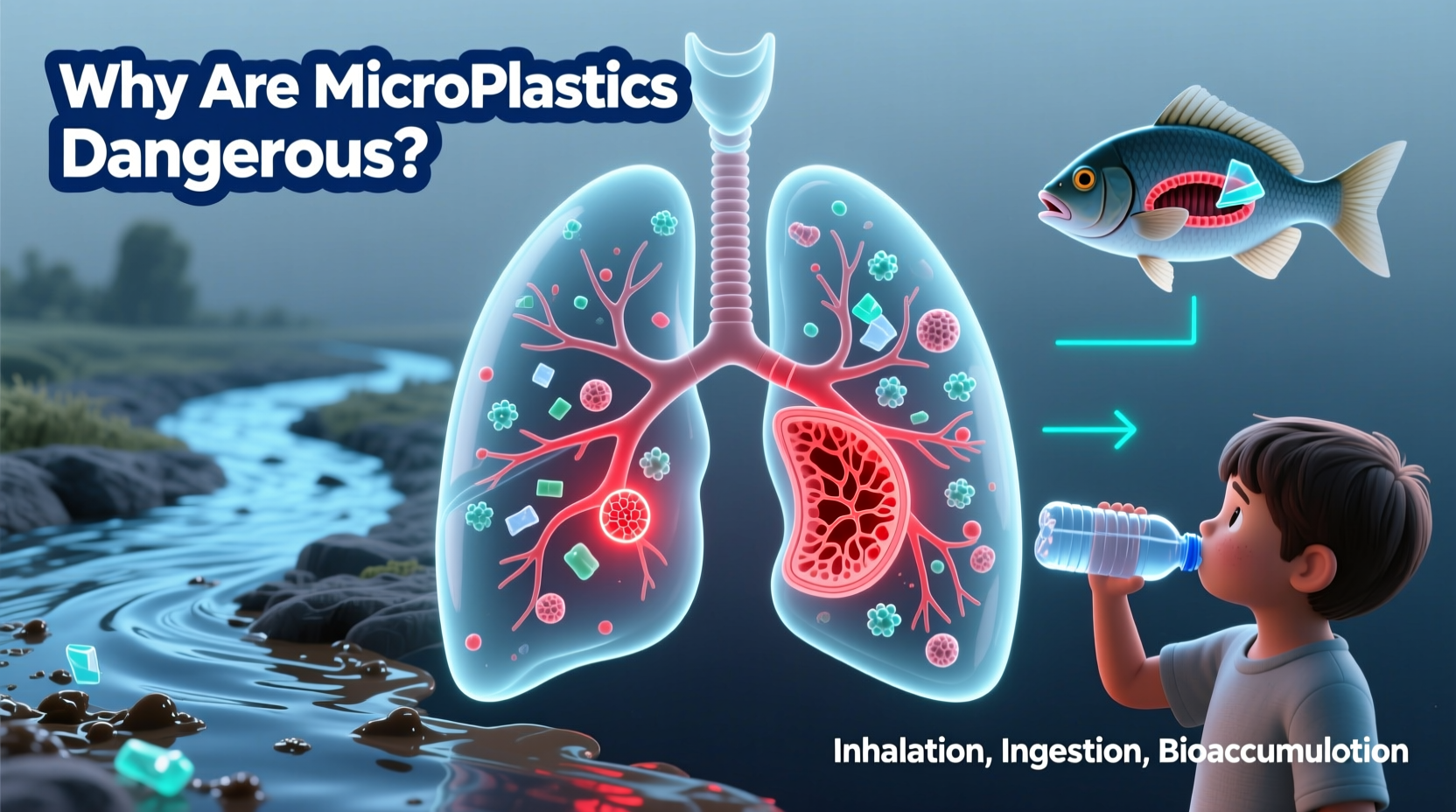

How Microplastics Enter the Human Body

Humans are exposed to microplastics through multiple pathways. The most common include ingestion, inhalation, and dermal contact. Studies have found microplastics in drinking water, seafood, table salt, beer, and even honey. Shellfish, which filter large volumes of water, often retain microplastics in their tissues, transferring them directly to consumers.

Inhalation is another major route, particularly in urban environments. Airborne microplastics from tire dust, synthetic textiles, and degraded plastic waste can be breathed in, lodging in lung tissue. Indoor air may be even more contaminated—carpets, curtains, and furniture made from synthetic materials continuously shed microfibers, especially when disturbed by movement or vacuuming.

A 2022 study published in *Environment International* detected microplastics in human blood, placenta, and brain tissue, confirming that these particles not only enter the body but also cross critical biological barriers. Once inside, they can persist for long periods due to the body’s limited ability to break them down.

Health Risks Associated with Microplastic Exposure

The danger of microplastics lies not just in their physical presence but in their chemical composition and ability to act as carriers for other toxins. Most plastics contain additives like phthalates, bisphenol A (BPA), flame retardants, and stabilizers—many of which are known endocrine disruptors linked to hormonal imbalances, reproductive issues, and developmental problems in children.

Additionally, microplastics absorb pollutants from their surroundings, including heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants (POPs) like PCBs and DDT. When ingested, these contaminated particles can leach harmful chemicals into tissues, increasing the risk of chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular damage.

“Microplastics represent a stealth exposure pathway. We’re still uncovering the full extent of their impact, but early evidence suggests they may contribute to metabolic disorders and immune dysfunction.” — Dr. Jane Collins, Environmental Health Researcher, University of Exeter

Animal studies have shown that high levels of microplastic exposure lead to reduced fertility, liver stress, and altered feeding behavior. While direct causal links in humans are still under investigation, the biological plausibility of harm is strong, especially given the cumulative nature of exposure.

Environmental Impact of Microplastics

The ecological consequences of microplastic pollution are equally alarming. Marine organisms—from plankton to whales—routinely ingest microplastics, mistaking them for food. This can lead to internal injuries, blockages, and false satiety, causing malnutrition and starvation. Coral reefs, already stressed by warming oceans, show reduced growth and increased disease susceptibility when exposed to microplastics.

On land, microplastics accumulate in agricultural soils through the application of sewage sludge as fertilizer. This affects soil biodiversity, impairing the function of earthworms and microbes essential for nutrient cycling. Plants can absorb nanoplastics (even smaller fragments), potentially introducing them into the food chain at the base level.

| Ecosystem | Impact of Microplastics | Key Affected Species |

|---|---|---|

| Ocean | Ingestion, entanglement, toxin transfer | Seabirds, fish, turtles, marine mammals |

| Freshwater | Altered metabolism, reproductive issues | Crustaceans, amphibians, freshwater fish |

| Terrestrial | Soil degradation, plant uptake | Earthworms, insects, crops |

| Atmospheric | Airborne transport, deposition | Humans, lichens, alpine ecosystems |

Reducing Personal Exposure: A Practical Checklist

While systemic solutions are essential, individuals can take meaningful steps to reduce their exposure and contribution to microplastic pollution. Consider the following actions:

- Choose natural fibers like cotton, wool, or linen over polyester, nylon, or acrylic clothing.

- Use a front-loading washing machine, which releases fewer microfibers than top-loading models.

- Install a water filter certified to remove microplastics, such as reverse osmosis or ultrafiltration systems.

- Avoid single-use plastics, especially bottles, straws, and packaging made from polyethylene or polystyrene.

- Opt for glass or stainless steel containers instead of plastic for food and beverage storage.

- Support brands that use recycled materials and transparent sustainability practices.

- Dispose of waste properly to prevent plastic from entering waterways and breaking down into microplastics.

Mini Case Study: The Tap Water Investigation

In 2021, a family in Portland, Oregon, began experiencing unexplained digestive discomfort. After ruling out common medical causes, they tested their tap water and discovered high levels of microplastics—mostly fibers and fragments below 10 micrometers. Upon installing a certified microplastic filter and switching to natural fabric towels, symptoms gradually improved. While correlation does not equal causation, the case highlights how household sources can contribute to exposure and how mitigation efforts may yield tangible benefits.

Policy and Innovation: Toward a Safer Future

Individual action must be matched by regulatory progress. Several countries have banned microbeads in cosmetics, and the European Union has proposed limits on tire wear and synthetic textile emissions. Improved wastewater treatment technologies, such as advanced filtration and ozone treatment, show promise in capturing microplastics before they reach rivers and oceans.

Innovation in material science is also critical. Biodegradable polymers, plant-based textiles, and circular economy models that prioritize reuse over disposal offer long-term solutions. However, these must be rigorously tested to ensure they do not simply shift the problem—some \"biodegradable\" plastics only break down under industrial conditions, not in natural environments.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can boiling water remove microplastics?

No, boiling water does not remove microplastics and may even increase concentration as water evaporates. Use a certified filtration system instead.

Are microplastics in sea salt a serious concern?

Yes, sea salt often contains microplastics due to seawater contamination. While occasional consumption is unlikely to cause immediate harm, regular intake adds to cumulative exposure. Opt for rock or lake salt if concerned.

How long do microplastics stay in the human body?

The retention time varies by particle size and location. Some pass through the digestive tract, while others embed in tissues and may remain for months or years. Research is ongoing.

Conclusion

Microplastics are no longer a hidden hazard—they are embedded in our bodies, our food, and our ecosystems. The evidence of their potential to cause harm is growing, and while science continues to unravel the full scope of risks, waiting for absolute certainty is not a safe strategy. Every choice to reduce plastic use, support sustainable innovation, and advocate for stronger environmental policies contributes to a healthier future.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?