Mushrooms are more than just forest floor curiosities or ingredients in gourmet dishes—they are essential players in the natural world’s recycling system. While they may appear inert or passive, mushrooms are actually the visible fruiting bodies of a much larger, hidden network that breaks down dead organic matter. This process is fundamental to life on Earth, ensuring nutrients are returned to the soil for reuse by plants and other organisms. But what exactly makes mushrooms decomposers? The answer lies in their biology, ecology, and unique metabolic capabilities.

The Role of Decomposers in Ecosystems

In every ecosystem, energy flows from producers (like plants) to consumers (like animals), but without decomposers, this cycle would eventually stall. When organisms die, their remains contain valuable nutrients such as carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus. If these materials were not broken down, they would remain locked in dead matter, depleting the soil and halting new growth.

Decomposers solve this problem by breaking down complex organic compounds—like cellulose, lignin, and chitin—into simpler forms that can be absorbed by plants. Among the most efficient decomposers are fungi, particularly those that produce mushrooms. Unlike bacteria, which often handle softer tissues, fungi specialize in dismantling tough plant materials that resist decay.

“Fungi are nature’s recyclers. Without them, forests would be buried under layers of undecomposed wood and leaves.” — Dr. Laura Simmons, Soil Microbiologist

How Mushrooms Function as Decomposers

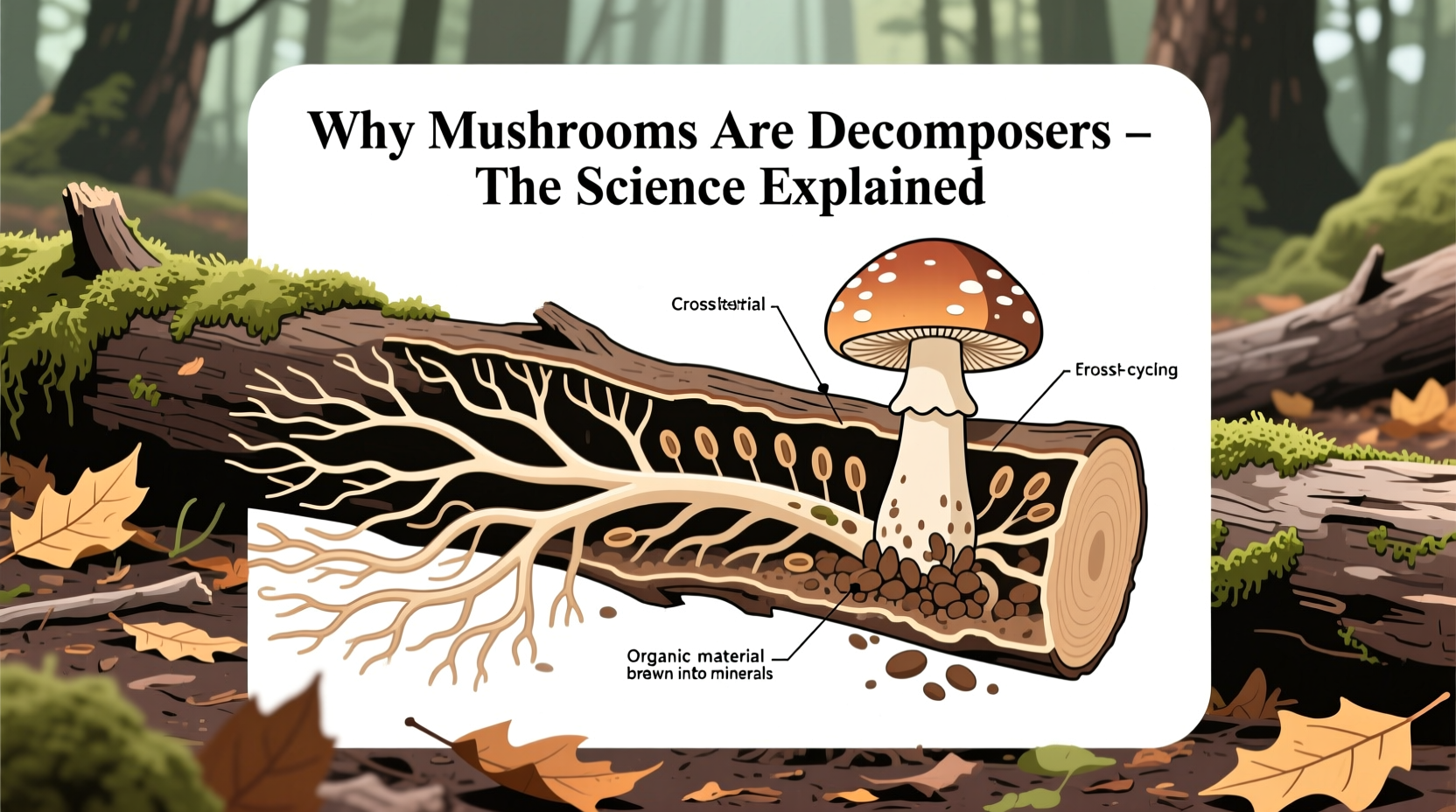

Mushrooms themselves are not the primary decomposing agents; they are the reproductive structures of fungi. The real work happens underground or within decaying material via a vast web of thread-like filaments called hyphae. These hyphae collectively form a network known as the mycelium, which permeates soil, logs, leaf litter, and other organic substrates.

The mycelium secretes powerful enzymes—such as cellulases, lignin peroxidases, and proteases—that break down large molecules into smaller, absorbable units. For example:

- Cellulase breaks down cellulose, a major component of plant cell walls.

- Lignin peroxidase degrades lignin, one of the most chemically resistant substances in nature.

- Proteases dismantle proteins into amino acids.

Once these compounds are broken down, the fungus absorbs the nutrients to fuel its own growth. In doing so, it releases byproducts like carbon dioxide and mineralized nutrients back into the environment, enriching the soil and supporting plant health.

The Science Behind Fungal Decomposition: Enzymes and Extracellular Digestion

Fungi employ a process known as extracellular digestion, which sets them apart from animals and many other organisms. Instead of ingesting food and digesting it internally, fungi release digestive enzymes into their surroundings. These enzymes act outside the fungal cells, breaking down polymers into monomers that can then be absorbed through the cell walls of the hyphae.

This method is especially effective in environments where nutrients are locked in solid form, such as fallen trees or compost piles. The ability to degrade lignin—a complex aromatic polymer that gives wood its rigidity—is a hallmark of certain mushroom-forming fungi, including species in the genera Phanerochaete, Ganoderma, and Trametes.

White-rot fungi, for instance, are among the few organisms capable of fully breaking down lignin, leaving behind a bleached, spongy residue. Brown-rot fungi, on the other hand, modify lignin but primarily target cellulose, causing wood to crumble into cubical fragments.

Comparison of Major Decomposer Fungi Types

| Type of Fungus | Substrate Targeted | Key Enzymes | Ecological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| White-Rot Fungi | Wood (especially hardwood) | Lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase | Complete breakdown of lignin and cellulose; enhances soil fertility |

| Brown-Rot Fungi | Coniferous wood | Cellulases, oxidative enzymes | Rapid cellulose degradation; contributes to humus formation |

| Saprophytic Mushrooms | Leaf litter, compost, dung | Proteases, chitinases, amylases | Recycles nitrogen-rich materials; supports garden soils |

Real-World Example: The Life Cycle of a Fallen Oak Tree

Consider a mature oak tree that falls in a temperate forest. At first, insects and bacteria begin breaking down the softer inner layers. But within weeks, fungal spores carried by wind or water land on the damp bark. Given the right moisture and temperature, these spores germinate and send out hyphae that penetrate the wood.

Over the next two to five years, white-rot fungi like Trametes versicolor (turkey tail) colonize the trunk, gradually transforming rigid lignin into simpler compounds. Mushrooms periodically emerge from cracks in the bark, releasing millions of spores to continue the cycle. By the end of this process, the log has become a rich, spongy mass teeming with microbial life—ready to nourish seedlings and support new forest growth.

This scenario illustrates how mushrooms, though short-lived, represent a critical phase in long-term ecological renewal. Their presence signals active decomposition and healthy nutrient cycling.

Practical Checklist: Supporting Natural Decomposition with Mushrooms

Whether you’re a gardener, conservationist, or nature enthusiast, you can harness the power of mushroom decomposers. Use this checklist to encourage beneficial fungal activity:

- Leave fallen branches and leaves in garden beds instead of removing them.

- Avoid excessive tilling, which disrupts mycelial networks.

- Add untreated wood chips or straw to compost to attract saprophytic fungi.

- Introduce mushroom spawn (like oyster or shiitake) into rotting logs for faster breakdown.

- Maintain consistent moisture levels in compost and mulched areas.

- Limit synthetic fungicides, which can harm beneficial fungi.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are all mushrooms decomposers?

No, not all mushrooms are decomposers. While most are saprophytic (feeding on dead matter), some form symbiotic relationships with plants as mycorrhizal fungi, helping roots absorb water and nutrients. Others are parasitic, feeding on living hosts. However, the majority of common woodland and garden mushrooms are decomposers.

Can mushrooms decompose plastic or pollutants?

Emerging research shows that certain fungi, including species like Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom), can break down hydrocarbons and even some plastics through enzymatic action—a process known as mycoremediation. While not yet scalable for widespread waste management, this highlights the untapped potential of fungal decomposers in environmental cleanup.

Do mushrooms only grow on dead material?

Most decomposer mushrooms prefer dead organic matter, but they can also colonize stressed or dying plants. Healthy, living trees typically resist fungal invasion due to chemical defenses, but once a tree begins to decline, saprophytic fungi move in quickly to start the decomposition process.

Conclusion: Embracing the Hidden Work of Mushrooms

Mushrooms may seem fleeting, appearing overnight and vanishing just as fast. But beneath their brief beauty lies a powerful biological engine driving one of nature’s most vital processes. As decomposers, they transform death into renewal, turning fallen trees, dead leaves, and organic waste into the foundation for future life.

Understanding their role deepens our appreciation for forest ecosystems, sustainable gardening, and the delicate balance of nutrient cycles. By protecting fungal habitats and supporting natural decomposition, we contribute to healthier soils, greener landscapes, and a more resilient planet.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?