Magnetism is a force we encounter daily—from refrigerator magnets to electric motors and MRI machines. Yet, despite its ubiquity, only a small number of materials exhibit strong magnetic properties. Why is that? The answer lies deep within the atomic structure of matter, where the behavior of electrons determines whether a material can become magnetic. Understanding this requires exploring quantum mechanics, electron alignment, and atomic interactions—all of which govern why iron sticks to a magnet while wood or plastic does not.

The Atomic Basis of Magnetism

All magnetism originates from the motion of charged particles, primarily electrons. Electrons possess two types of motion that contribute to magnetic properties: orbital motion around the nucleus and intrinsic spin. While both generate tiny magnetic fields, it’s the electron’s spin that plays the dominant role in determining whether a material becomes magnetic.

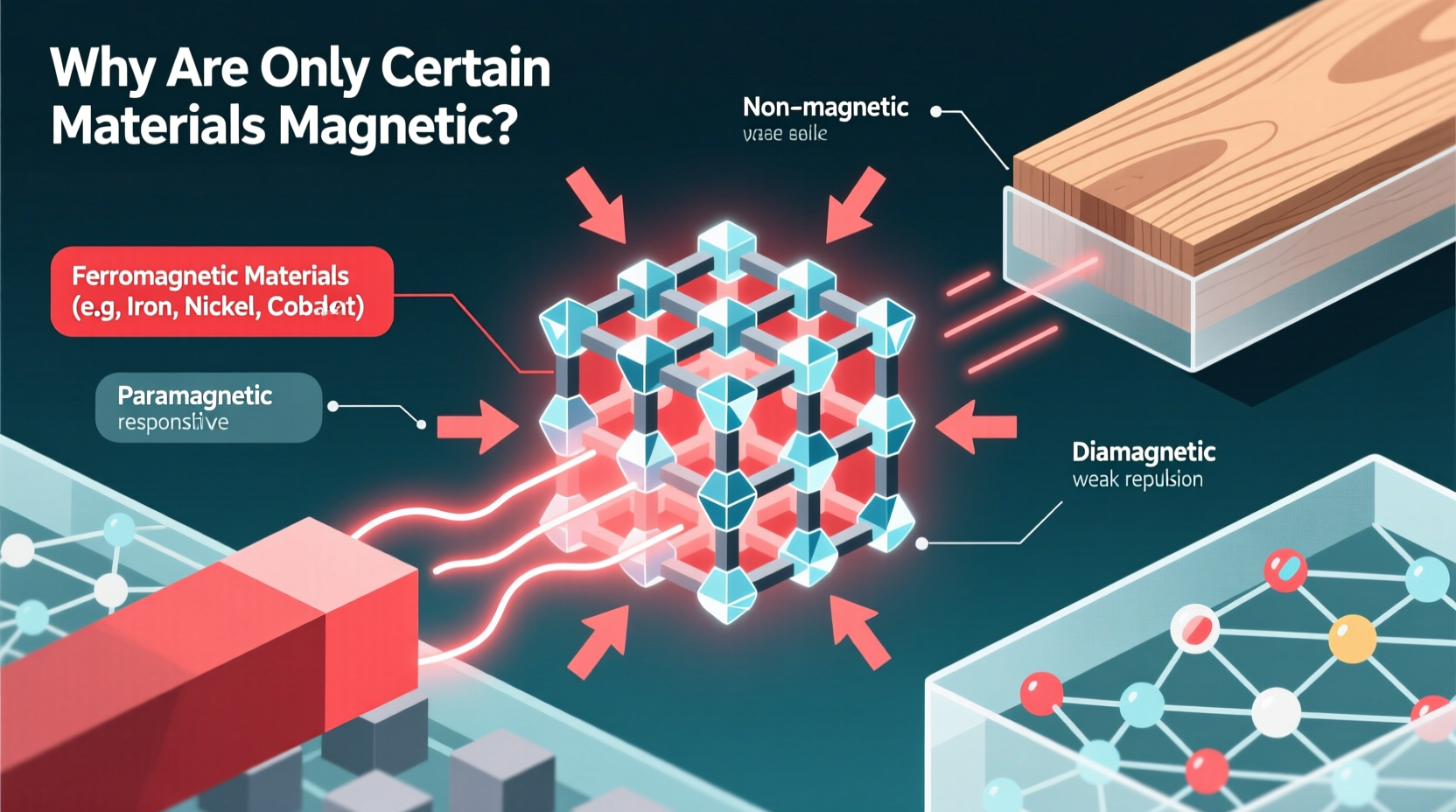

In most materials, electrons are paired such that their spins cancel each other out—one spins “up,” the other “down.” When all electrons are paired, there is no net magnetic moment, and the material remains non-magnetic. However, in certain elements—like iron, nickel, and cobalt—atoms have unpaired electrons in their outer shells. These unpaired electrons produce individual magnetic moments that can align under the right conditions, leading to macroscopic magnetism.

Types of Magnetic Materials

Materials respond to magnetic fields in different ways. Scientists classify them into five main categories based on their magnetic behavior:

| Type | Behavior | Example Materials | Permanent Magnet? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diamagnetic | Weakly repelled by magnetic fields | Water, copper, gold, bismuth | No |

| Paramagnetic | Weakly attracted, only when a field is present | Aluminum, platinum, oxygen | No |

| Ferromagnetic | Strongly attracted; can form permanent magnets | Iron, nickel, cobalt, gadolinium | Yes |

| Ferrimagnetic | Net magnetization due to unequal opposing spins | Magnetite (Fe₃O₄), ferrites | Yes |

| Antiferromagnetic | Adjacent spins oppose and cancel out | Manganese oxide (MnO) | No |

Ferromagnetic materials are the ones we commonly think of as “magnetic.” Their atoms have unpaired electrons and, crucially, a phenomenon called exchange interaction that encourages neighboring electron spins to align in the same direction. This alignment creates regions known as magnetic domains, where vast numbers of atoms act collectively like tiny magnets.

Domain Alignment and Permanent Magnetism

In an unmagnetized ferromagnetic material, these domains exist but point in random directions, canceling each other out. No net magnetic field is produced. However, when exposed to an external magnetic field, the domains that align with the field grow at the expense of others, and the boundaries between domains shift. If the field is strong enough, nearly all domains align, and the material becomes magnetized—even after the external field is removed.

This persistence is what defines a permanent magnet. Materials like neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) or alnico (aluminum-nickel-cobalt) retain their domain alignment due to high coercivity—resistance to demagnetization. In contrast, “soft” magnetic materials like pure iron lose their magnetism easily once the external field is gone, making them ideal for electromagnets but unsuitable for permanent ones.

“Magnetism isn’t just about having unpaired electrons—it’s about how those electrons interact with their neighbors. Long-range order is what turns atomic-scale magnetism into something you can hold in your hand.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Condensed Matter Physicist, MIT

Why Aren’t All Metals Magnetic?

It might seem logical that all metals would be magnetic, given their free-moving electrons. But magnetism depends not on electrical conductivity alone, but on electron configuration and crystal structure. For instance:

- Copper has a full outer d-shell, meaning its electrons are paired and produce no net magnetic moment.

- Aluminum has one unpaired electron but lacks the exchange interaction needed for spontaneous alignment—so it’s only weakly paramagnetic.

- Stainless steel varies: some grades (like 430) are ferromagnetic due to high iron content and crystal structure, while others (like 304) are austenitic and non-magnetic.

The key factor is the material’s electronic band structure and how atoms are arranged in the solid. Even if individual atoms are magnetic, their collective behavior depends on spacing, symmetry, and temperature. Above a critical temperature called the Curie point, thermal energy disrupts domain alignment, and ferromagnetic materials lose their magnetism entirely. Iron, for example, loses its ferromagnetism above 770°C (1,418°F).

Step-by-Step: How a Material Becomes Magnetic

- Atomic Structure: The material must contain atoms with unpaired electrons (e.g., Fe, Ni, Co).

- Exchange Interaction: Quantum mechanical forces encourage neighboring electron spins to align parallel.

- Domain Formation: Regions of aligned magnetic moments (domains) form spontaneously.

- External Field Application: A strong magnetic field causes domains aligned with the field to grow.

- Remanence: After the field is removed, sufficient alignment remains to produce a net magnetic field.

Real-World Example: The Case of Magnetic Stainless Steel Appliances

Many people are surprised to find that some stainless steel refrigerators attract magnets while others do not. This variation stems from differences in alloy composition and crystalline structure. Ferritic stainless steels (common in appliances) contain chromium and iron in a body-centered cubic structure that supports ferromagnetism. In contrast, austenitic stainless steels (like 304 grade) have a face-centered cubic lattice that prevents domain alignment, making them non-magnetic—even though they contain iron.

A manufacturer choosing materials for a kitchen appliance must balance corrosion resistance, cost, and functionality. If magnetic mounting (for notes or accessories) is desired, they’ll opt for a ferritic blend. Otherwise, the more corrosion-resistant austenitic type may be preferred. This real-world trade-off illustrates how microscopic magnetic properties influence everyday design decisions.

FAQ: Common Questions About Magnetic Materials

Can non-magnetic metals become magnetic?

Generally, no—unless they undergo structural changes. For example, mechanical stress or phase transformation in certain steels can induce martensite formation, which is ferromagnetic. Also, extremely strong magnetic fields can induce weak magnetism in paramagnetic materials, but it disappears when the field is removed.

Why is iron magnetic but rust (iron oxide) less so?

Rust (Fe₂O₃) has a different atomic arrangement than pure iron. Its electrons are locked in a crystal lattice that favors antiferromagnetic ordering—where adjacent spins oppose each other. This results in little to no net magnetism, unlike metallic iron, where domains can align freely.

Are there magnetic liquids?

Yes—ferrofluids are colloidal suspensions of nanoscale ferromagnetic particles in a liquid carrier. They respond strongly to magnetic fields and are used in engineering seals, loudspeakers, and medical applications. However, the liquid itself isn’t inherently magnetic—the suspended particles provide the response.

Conclusion: Embrace the Science Behind the Attraction

Magnetism is not magic—it’s the result of precise atomic conditions coming together: unpaired electrons, favorable quantum interactions, and stable domain structures. Only specific materials meet all these criteria, which is why magnetism remains a selective property in nature. From the compass needle to data storage in hard drives, our ability to harness this phenomenon relies on understanding these fundamental principles.

Whether you're selecting materials for a project, troubleshooting a device, or simply curious about the world, recognizing why only certain materials are magnetic empowers you with deeper insight. The next time you snap a magnet onto your fridge, remember—it’s not just sticking. It’s physics in action.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?