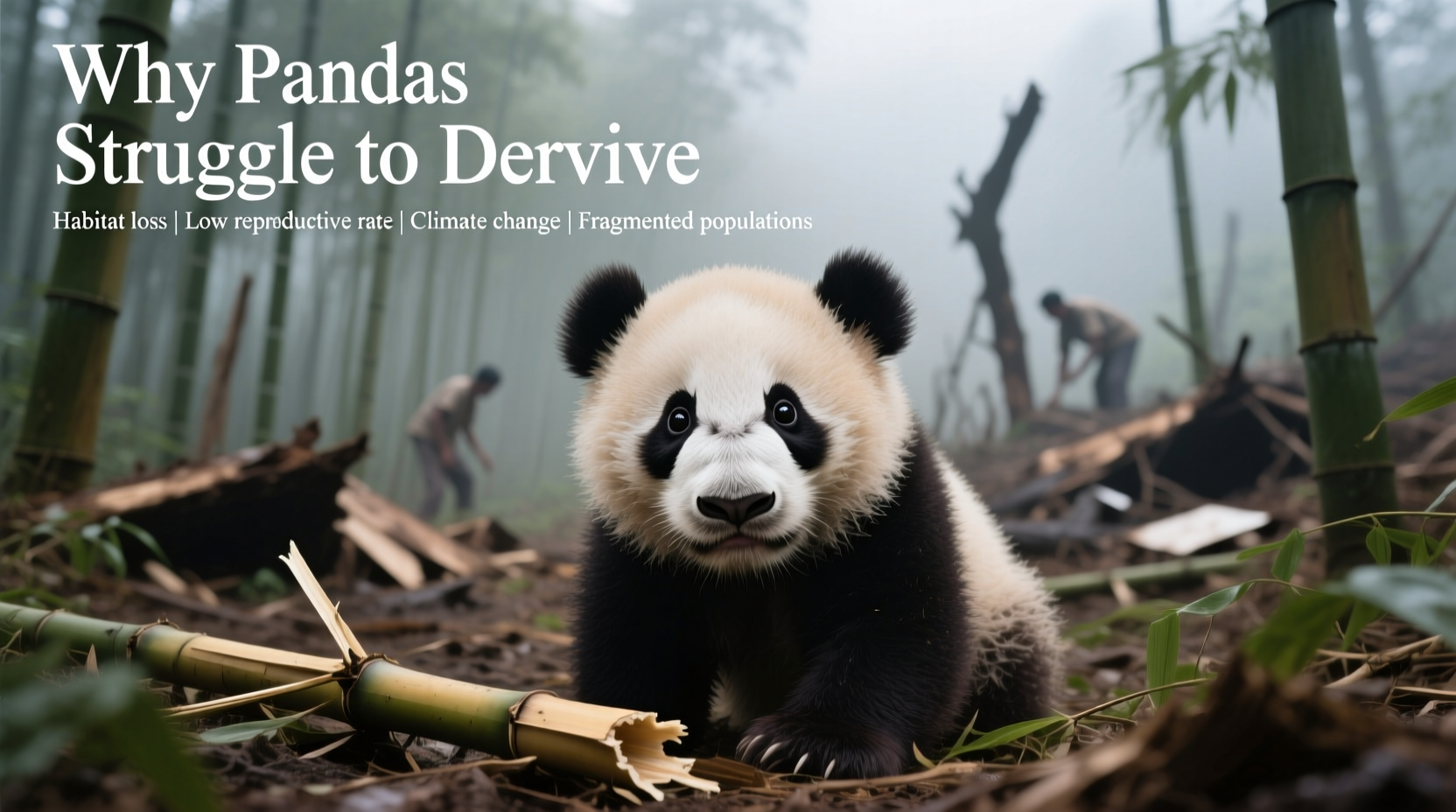

The giant panda is one of the most iconic animals on Earth—beloved for its distinctive black-and-white fur and gentle demeanor. Yet despite global admiration, this species has long teetered on the edge of extinction. While conservation efforts have brought the panda from “endangered” to “vulnerable,” it remains a fragile species with unique challenges to survival. Unlike many animals that adapt to changing environments, pandas face a combination of biological inefficiencies, habitat limitations, and reproductive difficulties that make natural survival exceptionally difficult.

Understanding why pandas are inherently poor survivors isn’t about criticizing evolution—it’s about recognizing the vulnerabilities that demand targeted human intervention. From their specialized diet to low reproductive rates, the panda’s biology defies many principles of evolutionary success. This article explores the core reasons behind their survival struggles and how modern conservation strategies are working to overcome them.

Dietary Specialization: The Bamboo Trap

Pandas are classified as carnivores, yet 99% of their diet consists of bamboo—a plant low in nutrients and difficult to digest. Their digestive system remains largely unchanged from their meat-eating ancestors, lacking the specialized gut flora typical of herbivores. As a result, pandas extract only about 17% of the energy from the bamboo they consume, forcing them to eat between 12 to 38 kilograms daily—up to 14 hours of feeding per day.

This extreme dietary specialization creates multiple problems:

- Vulnerability to food scarcity: Bamboo forests flower and die off cyclically every 30–120 years, wiping out entire stands. Pandas cannot switch to alternative foods easily and may starve during these die-offs.

- Habitat inflexibility: Pandas must remain near dense bamboo groves, limiting their range and making relocation difficult.

- Energy deficit: With so much time spent eating, pandas have little energy left for reproduction, territorial defense, or evading predators.

Reproductive Challenges: Nature’s Bottleneck

Pandas face some of the most daunting reproductive obstacles among mammals. Female pandas ovulate only once a year, and their fertile window lasts just 24 to 72 hours. Males must detect subtle behavioral and chemical cues to time mating correctly—a challenge in fragmented habitats where individuals rarely encounter each other.

Even when mating is successful, complications persist:

- Pregnancy can involve delayed implantation, making gestation periods unpredictable (ranging from 72 to over 320 days).

- Females often give birth to twins but typically raise only one cub due to limited energy and maternal capacity.

- Newborn cubs weigh only 90–130 grams—about 1/900th of the mother’s weight—the smallest ratio of any placental mammal—making them extremely vulnerable.

“Panda reproduction is a race against time and biology. We’re not just conserving a species—we’re compensating for nature’s narrow margins.” — Dr. Ling Zhao, Senior Reproductive Biologist, Chengdu Research Base

Habitat Fragmentation and Human Encroachment

Historically, pandas roamed across southern China, Myanmar, and Vietnam. Today, their range is reduced to isolated pockets in Sichuan, Shaanxi, and Gansu provinces. Over 60% of remaining panda populations live in fragments smaller than 100 square kilometers, separated by roads, farms, and settlements.

This fragmentation leads to:

- Inbreeding: Small, isolated groups lead to reduced genetic diversity, increasing susceptibility to disease and reducing fertility.

- Migration barriers: Young pandas seeking new territories cannot safely cross human-dominated landscapes.

- Resource competition: Local communities rely on forest resources, sometimes leading to conflict over land use.

| Conservation Challenge | Natural Factor | Human Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Diet limitation | Bamboo dependency, inefficient digestion | Deforestation reduces bamboo availability |

| Low reproduction | Short breeding window, small litter size | Habitat loss limits mate access |

| Genetic health | Small natural population | Fragmentation prevents gene flow |

| Cub survival | Altricial young, high mortality | Disturbance increases abandonment risk |

Conservation Successes and Ongoing Strategies

Despite these challenges, coordinated conservation efforts have reversed the panda’s decline. Since the 1980s, China has established 67 panda reserves covering over 1.4 million hectares. Reforestation programs and bamboo corridor projects aim to reconnect isolated populations.

Key strategies include:

- Captive breeding and reintroduction: Facilities like the Chengdu Panda Base use artificial insemination and foster care to boost cub survival. Some individuals are trained for wilderness skills before release.

- Community engagement: Locals are employed as forest rangers or eco-tourism guides, reducing reliance on logging and farming in panda zones.

- Corridor development: Wildlife bridges and protected pathways allow pandas to move between habitat patches safely.

Mini Case Study: The Story of Qizai

Qizai, meaning “Seven Cubs,” is a male panda born in captivity who failed to breed naturally despite repeated attempts. After hormonal therapy and behavioral training, he successfully sired offspring through artificial insemination. His genes were critical in diversifying the captive gene pool. Today, several of his descendants live in semi-wild enclosures designed to simulate natural conditions—part of a broader effort to prepare pandas for eventual rewilding.

Action Checklist: How Conservation Works in Practice

- Monitor wild populations via camera traps and GPS collars

- Plant mixed-species bamboo forests to prevent monoculture collapse

- Use artificial insemination to maximize genetic diversity

- Train captive-born pandas in foraging and predator avoidance

- Engage local communities in sustainable livelihood programs

- Advocate for infrastructure planning that avoids critical habitats

Frequently Asked Questions

Why don’t pandas evolve to eat other foods?

Evolution operates over millions of years, and pandas have only been bamboo specialists for about 2 million years. Their anatomy—especially teeth and jaw structure—is adapted to crushing fibrous plants, but their digestive tract hasn’t caught up. Rapid environmental change outpaces slow evolutionary adaptation, especially in a species with low genetic variation and long generational turnover.

Are pandas still endangered?

As of 2021, the IUCN Red List downgraded giant pandas from “Endangered” to “Vulnerable” due to population growth—from fewer than 1,200 in the 1980s to over 1,800 today, including both wild and semi-wild individuals. However, climate models predict that bamboo habitat could shrink by more than 35% by 2070 due to warming temperatures, threatening future stability.

Can pandas survive without human help?

In the current state of fragmented ecosystems and climate instability, it is unlikely. While some populations are stable within protected reserves, the combination of low reproduction, dietary constraints, and habitat vulnerability means pandas remain dependent on active management. Without ongoing conservation, experts believe populations would decline rapidly.

Conclusion: A Symbol of Hope and Responsibility

The panda’s struggle for survival is not a failure of nature, but a reflection of how deeply human activity has reshaped the planet. Their biological quirks—once manageable in vast, connected forests—are now liabilities in a world of borders, roads, and climate uncertainty. Yet the very fact that we’ve pulled them back from the brink shows what focused, science-based conservation can achieve.

Pandas remind us that preservation isn’t just about saving a single species—it’s about restoring balance, protecting ecosystems, and acknowledging our role in both destruction and recovery. They are not “bad” at surviving; they are mismatched to a world that has changed too fast. Our responsibility is to ensure that mismatch doesn’t become a death sentence.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?